“Most of what I read while I’m working on a book is research material, accompanied by buoyant distractions like detective novels,” says the British writer Olivia Laing. “But there’s another, much smaller category, too: books so brilliantly strange that they nudge me back to writing when I’ve got jammed or run aground.” Laing is the author of several books, including The Lonely City (2016) and Crudo, out in paperback in September, and is at work on a collection of essays on art and politics, to be published by W. W. Norton next spring. Here, she chooses the books that “shunt straight past the mundane, pinpointing territories and moods I recognize, absolutely, and yet find so difficult to articulate that I sometimes feel like applauding as I read. I’ll tell you what they’re like: elevators that will take you to an unmarked floor, where everything is bathed in a new, astonishing light.”

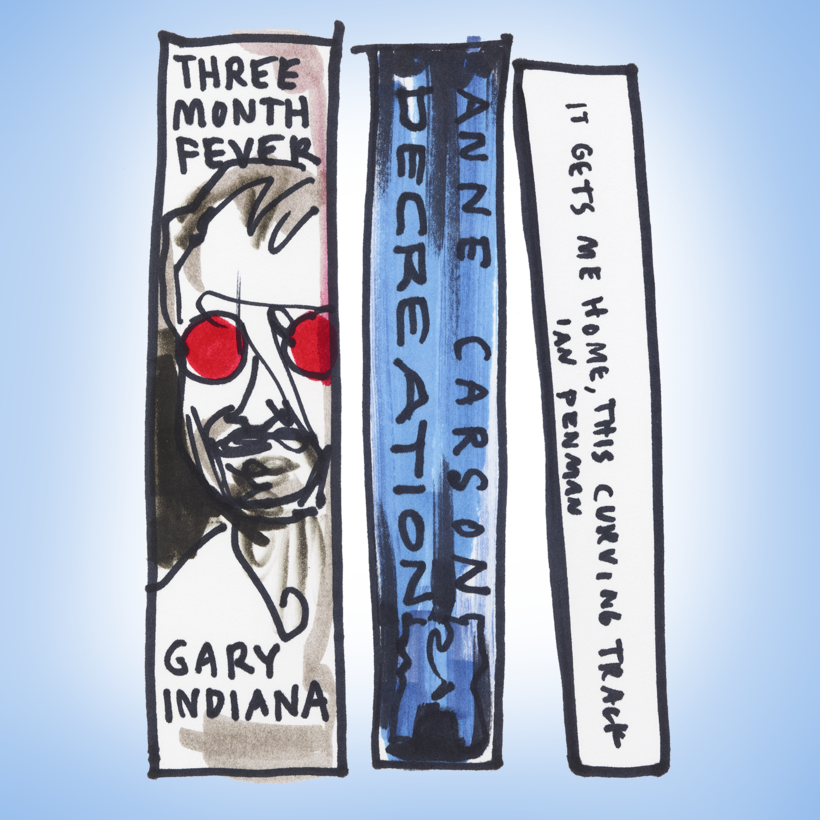

Three Month Fever, by Gary Indiana

This is a serial-killer novel from 1999 that’s actually a moral portrait of an America besotted with money and celebrity. There’s no one to match Indiana for savage insight and impeccable style, and his account of the Gianni Versace murderer, Andrew Cunanan, so far exceeds the true-crime genre that it should be required reading for anyone keen to understand the darkening 21st century.