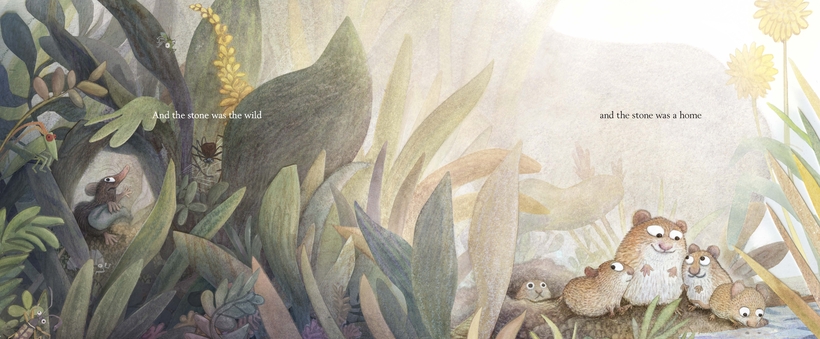

A single stone, rock, boulder, or whatever may strike you as an implausible subject for a picture book. And true, after the folktale Stone Soup and William Steig’s Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, the shelf of first-rate lithologic literature for children lies fairly empty. So kudos to Brendan Wenzel for A Stone Sat Still, which, as the title suggests, is about a stone that’s not even animate, let alone magic. The cover art ups the ante by depicting a snail on top of the titular stone, almost as if Wenzel is daring himself to write the quietest, slowest, stillest book imaginable—or daring readers to pick it up.

He is the right person for the challenge: this is Wenzel’s third book as both author and illustrator, following They All Saw a Cat (2016), a Caldecott Honor winner, and Hello Hello (2018). All are wonderful. A Stone Sat Still echoes the ingenious They All Saw a Cat in that both are essays in perspective and relativity. In the former, the same cat is shown as seen from the P.O.V.’s of, among others, a dog (cat as creepy, slinky lowlife), a mouse (cat as nightmare predator), and a flea (my favorite: cat as vast furry parkland).