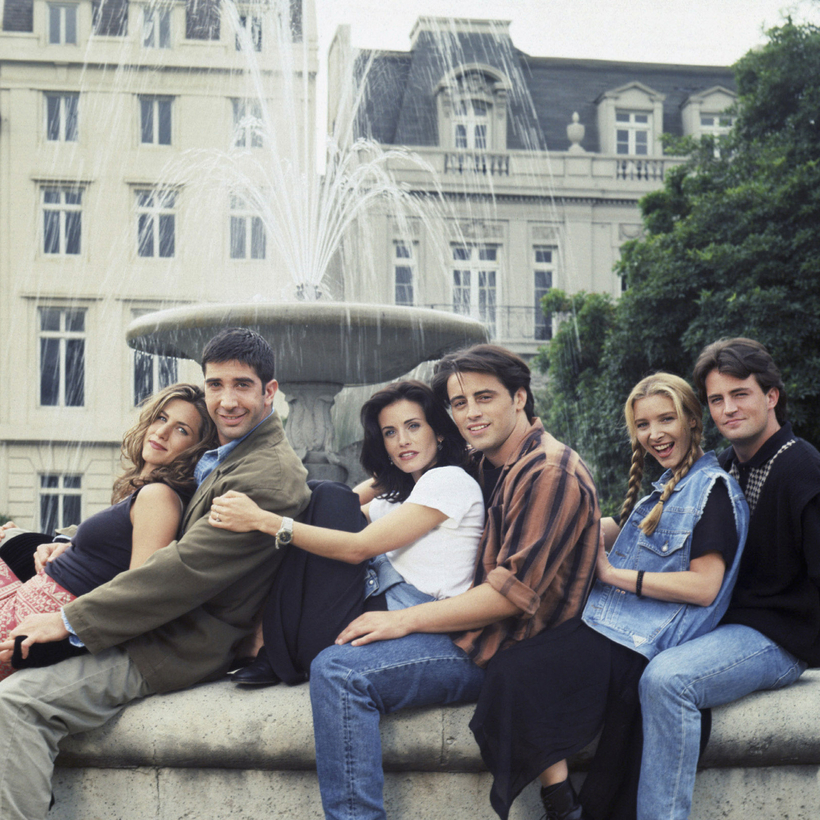

Saturday afternoon. My 13-year-old goddaughter and I sit on the sofa and watch four episodes of Friends, back-to-back. I’ve seen them a hundred times before; so, apparently, has she, but this doesn’t bother us. We are equally rapt. We laugh at the same bits. We anticipate the same lines.

“Which one do you fancy?” she asks, at some point.