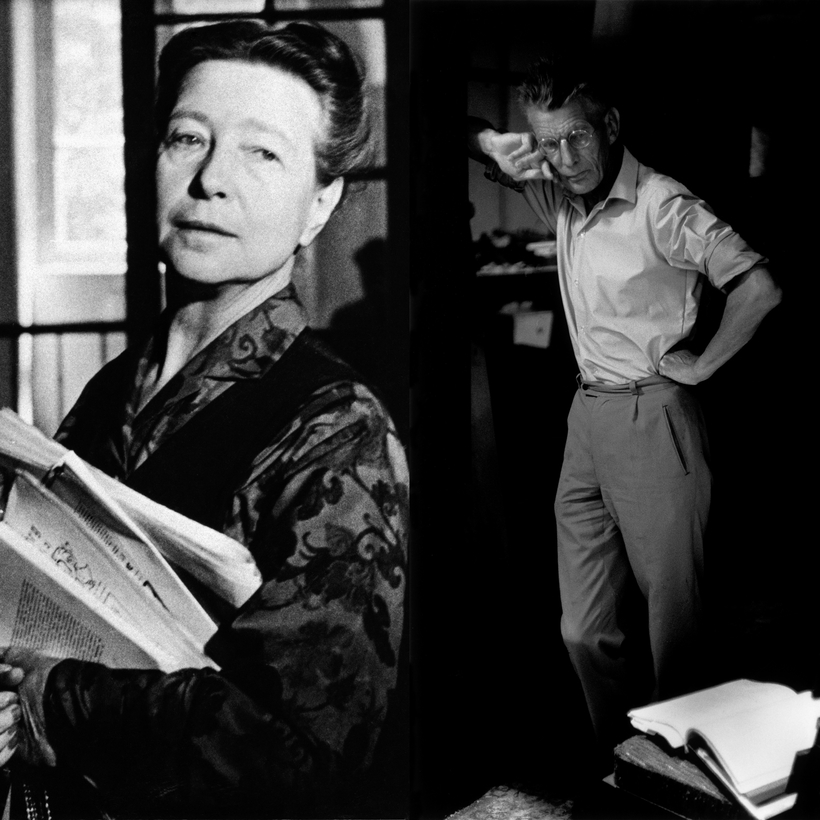

“So you are the one who is going to reveal me for the charlatan that I am.” This was the first thing Samuel Beckett ever said to me, on a cold November day in 1971 when I, a newly minted twentysomething Ph.D. who had never read biography and had no idea how to write it, decided that he needed one and that I was the person to write it.

Earlier, I had written a letter saying I didn’t believe he was only the “poet of alienation, isolation, and despair,” as all the critics so deeply steeped in French literary theory described him. I found so many resonances from my readings in Irish history and literature of real people and places in his writing that came from his upper-class Anglo-Irish upbringing. I didn’t keep a copy of the letter but it must have been fairly pompous; I presented myself as the perfect scholar-writer to set the literary record straight. To my amazement, he replied swiftly, saying that if I came to Paris, he would be happy to see me.