Not too long ago, satire was a dirty word in Hollywood. The studios thought it too dark and political, and a bit of a slippery eel as far as marketing was concerned. Why couldn’t these pesky writers just stick to square-jawed heroes averting the apocalypse and maneuvering grateful beauties into bed? But the era of peak television has proved that audiences are more than capable of handling stiff social commentary, and dramatic lurches in world events have created an appetite for timely tales. And when it comes to cinema’s keen observers of the times, writer-director Bong Joon-ho (Snowpiercer, Okja), one of South Korea’s most celebrated auteurs, stands at the forefront.

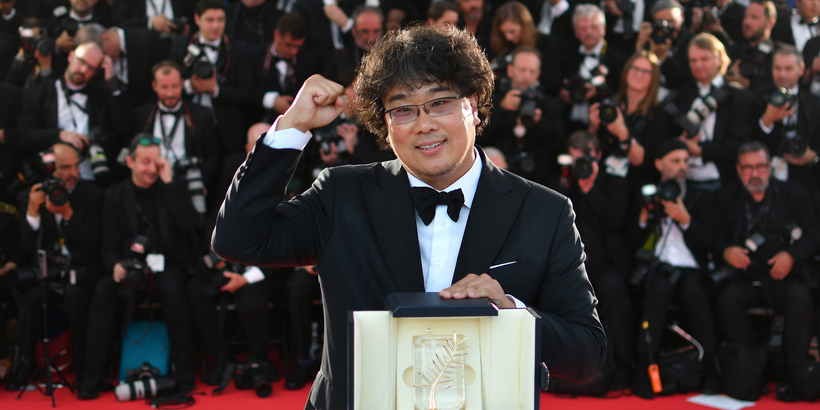

His new film, Parasite, which Bong calls a tragicomedy, just opened this week, but it’s already enjoying a remarkable run. In May, the director accepted the Palme d’Or at Cannes, making him the first Korean director ever to win the award. The head of the jury, Alejandro González Iñárritu, an equally inventive director, praised the film as “a unique experience. It’s so unexpected.” For Bong, the moment was “incredibly surreal,” he says. “It felt like I was directing and shooting the scene of my own speech.”