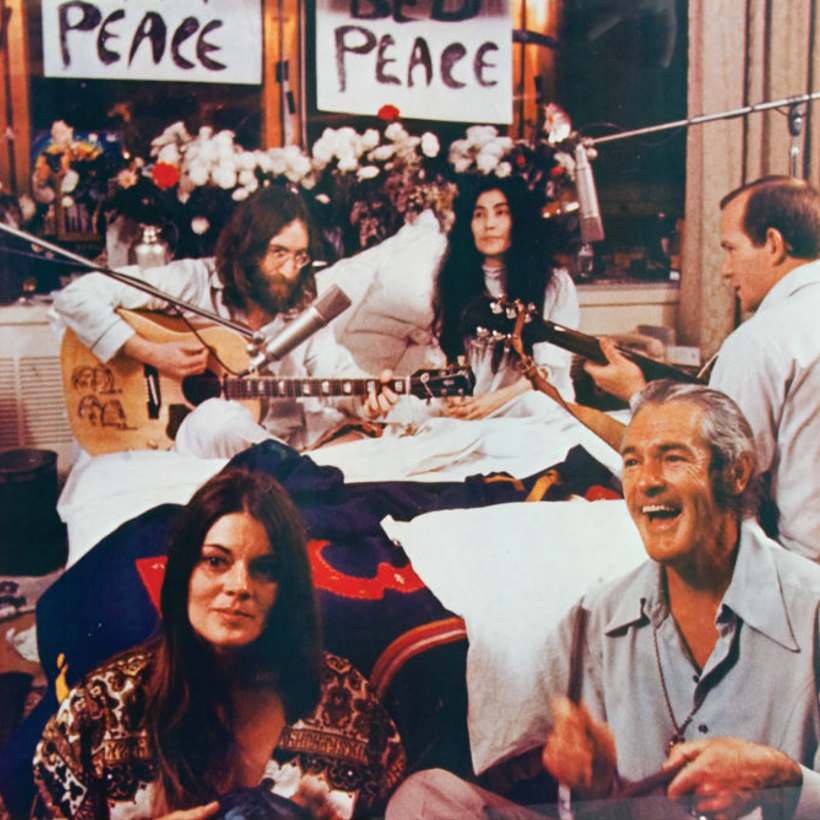

The image is seared into our collective imagination: Yoko Ono and John Lennon, draped in white robes, reclining during their 1969 Bed-In protest against the Vietnam War in a Montreal hotel suite.

I’m sure it comes as swiftly to your mind’s eye as it does to mine. Still, there’s a good chance you’ve overlooked something—or someone. Look again. Let your eye wander. In the foreground, nearly centered in the shot, is a striking brunette. She sits beside her husband, the silver-haired acid guru Timothy Leary, who smiles wide, clapping and singing along to the song Lennon and Ono recorded on-site: “Give Peace a Chance.”

Unlike her husband, she’s not swept up in the moment. Instead, she looks directly at the camera, lips pursed in a mysterious Mona Lisa smile. She stares at you, the viewer, with a look appropriate for a woman who lived her life at the edge of the frame. A woman who helped shape the counterculture movement of the 1960s yet was erased from its history.

Her name is Rosemary Woodruff Leary, and I spent five years learning about her to write her biography, The Acid Queen—and to give her the credit she has long been owed. She helped shape the legacy of 1960s counterculture—co-writing her husband’s speeches, crafting his most controversial slogans, sewing his clothing, and preserving his archives, which are now housed in the New York Public Library. Her influence on the psychedelic movement is especially resonant today. But my favorite of her contributions is something far more concrete: an offhand witticism that helped birth one of the most well-known songs in pop-culture history.

Like the Bed-In image, the song transcends generations. I’d bet you can identify it from the dark, groovy throb of the bass line—well before the opening line: “Here comes old flat-top.”

“Come Together” opened The Beatles’ 1969 album Abbey Road. The song is mysterious, gritty, and a little unsettling. And Rosemary came up with its memorable chorus.

Ten days before the Bed-In, the controversial former Harvard professor turned acid proselytizer Timothy Leary announced plans to run for governor of California against the incumbent, Ronald Reagan. Rosemary was not pleased. Even she could see that this would unsettle the eyes of the Establishment.

Still, she campaigned with him and posed for the press and political posters. When Timothy made his candidacy official, it wasn’t his run but theirs.

“I’m going to run—no, no—we’re going to fly with my mate [Rosemary] for the governorship of California in 1970,” he said. “There’s going to be high taxes.”

“Your wife gives you all those ad-libs, doesn’t she?” a reporter asked.

“My best lines come from Rosemary.”

One of those lines would become their campaign slogan: “Come together, join the party.”

During an interview with the underground paper the Berkeley Barb in February of 1969, Rosemary and Timothy riffed on the phrase.

“What are the words to it, my dear?,” Timothy asked as Rosemary entered the room, her hair wrapped in a towel after coming out of the shower.

“Don’t come alone, come together—it’s the only way to come,” she sang. “Don’t go away, come along, join the party. Everybody has got to come sometime. Come now!”

They brought the slogan to John Lennon—who had been an admirer of Leary’s since reading his 1964 LSD-trip guide, The Psychedelic Experience—at his Bed-In, hoping he might turn it into a campaign song.

“Great title,” Lennon reportedly said.

Ultimately, Timothy Leary’s campaign ended in prison, for marijuana possession, and there would no longer be any need for a song. The slogan then became something else entirely—a Beatles No. 1 hit. Lennon and Leary later fought over the song’s origin, never mentioning the woman who sparked it all.

But Rosemary Woodruff Leary was once again just outside the frame—watching, shaping, and smiling that mysterious smile.

Susannah Cahalan is a New York–based writer and the author of Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness