Lan P. Duong, and Viet Thanh Nguyen

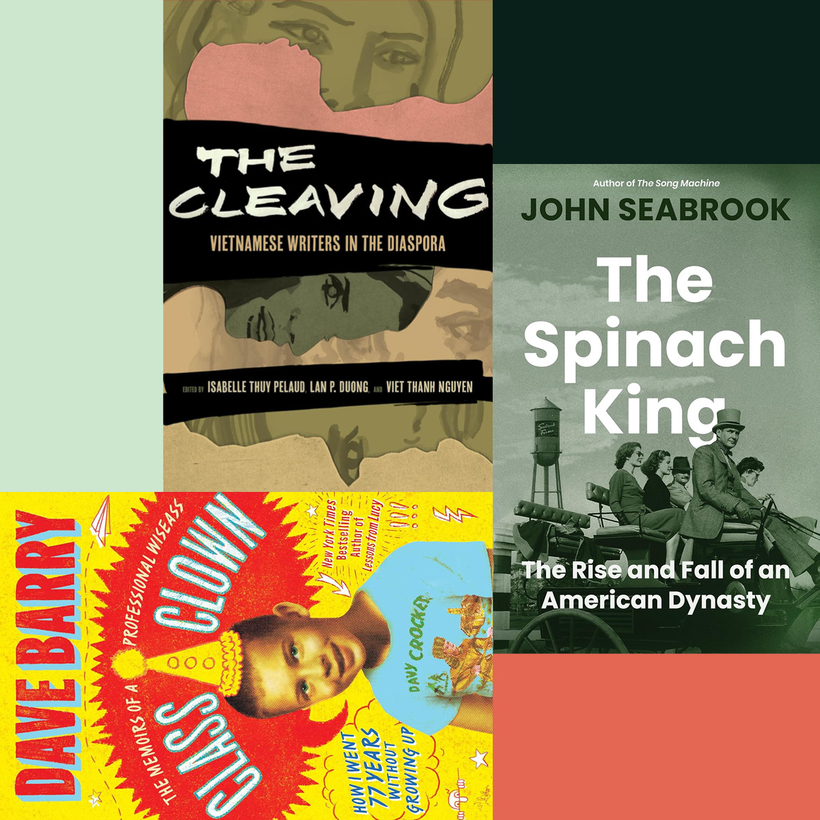

It has been 50 years since the war ended in Vietnam, yet for decades afterward Vietnamese writers have rarely been published in the English language. The Cleaving is remarkable in making amends, featuring three dozen writers, poets, and artists in the Vietnamese diaspora in paired dialogues. The result is an affecting kaleidoscope of perspectives and feelings that tears away the Western image of the country, seen “too often as a country of war, at times a leftist revolutionary fantasy, and now a viable site for capitalistic investment.” The conversations range from why Americans do not like to discuss the war to the difficulties of finding an agent, to the challenges of writing stories that do not fit a certain preconception. Or as the novelist and poet Amy Quan Barry put it, “You can’t write about Vietnam unless you include a water buffalo somewhere.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen is the most famous of them all, thanks to winning the Pulitzer Prize in fiction for The Sympathizer, and his foreword eloquently explores the problems faced by those who, no matter how well they write, may still hear comments such as “Your English is so good!” His goal for the book is to show that there is “narrative plenitude” in Vietnamese voices, and it is a goal fully achieved in The Cleaving with both insight and wit.

Who knew that a family empire built on frozen vegetables could produce a tale worthy of Faulkner, this time set in the farmlands of southern New Jersey, complete with gangsters, labor woes, strike breakers, and, ultimately, a shattered family. Oh, and there is also anti-Semitism, alcoholism, Swiss bank accounts, white Lipizzan horses, and a missing safe. John Seabrook, a longtime staff writer at The New Yorker, is the grandson of C. F. Seabrook, once hailed as the Henry Ford of agriculture, and C.F.’s rupture with Seabrook’s father, Jack, not only led to the company being sold but to Jack’s loss of vocation and eventual descent into a Fox News–loving reactionary. If revenge is a dish best served cold, Seabrook’s detailed exposé of his grandfather and his malevolence is, appropriately enough, served frozen solid.

If Seabrook had chosen lima beans over writing we would never have had The Spinach King to savor, as rich a tale about a troubled dynasty—and father-son relationships—as you will read this year. It is also a story of redemption, as Seabrook gets sober, adopts a baby from Haiti, and confronts his damaged relationship with his own father. The book is dedicated to his wife, Lisa. She deserves it.

Thank God, a humor book that is actually funny. Dave Barry is now 77 years old, but he ruled the syndicated-newspaper-columnist world for more than 20 years before anyone currently under 20 was born. Indeed, his exploits inspired a TV show called Dave’s World, which starred the late Harry Anderson. This is his memoir, which partly means revisiting gems from his columns, such as the motto of Miami International Airport (“You Expect to Get Your Luggage BACK?”) and what it’s like to prepare for a colonoscopy: “The instructions for MoviPrep, clearly written by somebody with a great sense of humor, state that after you drink it, a loose watery bowel movement may result. This is kind of like saying that after you jump off your roof, you may experience contact with the ground.”

The meat of the book, and it is all fresh and prime, is about how a kid born in Armonk, New York, came to be such a funny guy. He credits his mother, by the way, for her “sharp, dark sense of humor coiled inside her, always ready to strike.” It is a measure of Barry’s talent that he deals with his dad’s drinking and his mom’s suicide with a sensitivity that never wallows in pity. If anyone thinks Barry’s humor is sophomoric, Barry would be the first to agree, though let the record show he won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for commentary. After all, weren’t we all at our funniest during sophomore year in high school? The difference is that Barry was and still is funnier than the rest of us.

Jim Kelly is the Books Editor at AIR MAIl. He can be reached at jkelly@airmail.news