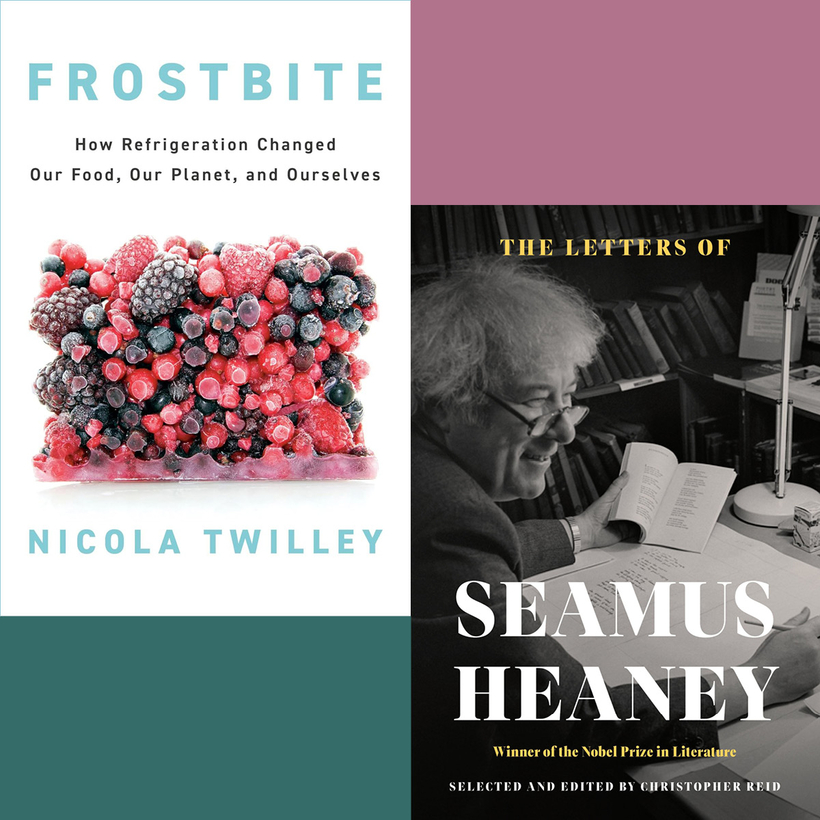

Quick. Name some inventions from the 20th century that changed our everyday lives. Cell phones, check. Airplanes, computers, cars, television, all worthy of mention. But if you did not think of refrigeration, and even if you did, this riveting account of how we manufactured cold is popular history at its best. Only after World War I did home refrigerators become available, and in General Electric’s case the company made them primarily as a way to sell more electricity. Industrial refrigeration revolutionized how and what kind of food made it into those fridges; for example, growers could now ship other kinds of lettuce rather than just iceberg, the variety that was best able to survive non-refrigerated trucking. Today, nearly two-thirds of all fruits and vegetables grown in the world are eaten in a country other than the one in which they were produced.

Nicola Twilley is at her most entertaining profiling the obsessives who, through trial and error, made it possible for New Zealand kiwifruit to “spend up to seven weeks wending its way around the Indian Ocean and through the Suez Canal and the Strait of Gibraltar” before ending up in a London fruit salad. Not everyone embraced refrigeration in its early days, and Twilley makes the persuasive argument that its effects on the kind of food we eat and on the environment will make you think twice about eating a fresh peach out of season.