and Marie Delbarre

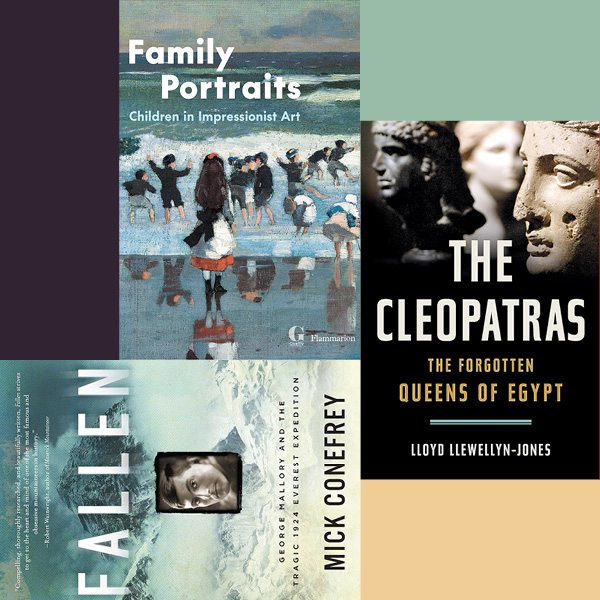

This volume, put together by Cyrille Sciama and Marie Delbarre, is the catalogue that accompanied an exhibition presented last year by the Musée des Impressionnismes Giverny, and it is an utter delight. What was it like to be the children of Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro, and how did they shape their parents’ view of children in their artwork? The cheerful images on canvas both supported and belied the reality of family lives before World War I, but even childless painters such as Cassatt and Degas found inspiration in painting children. One of the most intriguing paintings is of a pre-teen Jean Monet, staring uncertainly at the viewer as if curious about what his father, Claude, expects of him: a model child or a child model? The book also includes works by later artists, including many photographs, illustrating striking similarities between masters old and new.

There is the famous Cleopatra, who ruled what was then the wealthiest country in the world and who has been immortalized, for better and for worse, on stage and screen, and then there are the six Cleopatras who preceded her, whose lives and deeds have largely disappeared under the sands of time. Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones does a masterful job blowing all that sand away, while at the same time erasing some of the cartoonish aspects of the last and best known Cleopatra: VII. Greek-speaking descendants of Ptolemy, who helped Alexander the Great conquer Egypt, all seven proved to be ruthless strategists in a patriarchal world, with more than its share of incest, murder, and constant plotting. Even at the end of her reign, defeated by the Romans, the last Cleopatra outfoxed her captor’s desire to parade her through the streets by killing herself. (Whether this was achieved by the bite of an asp or by using a hair comb to prick her skin and applying the poison that way is still unclear.) This is historical drama at its best.