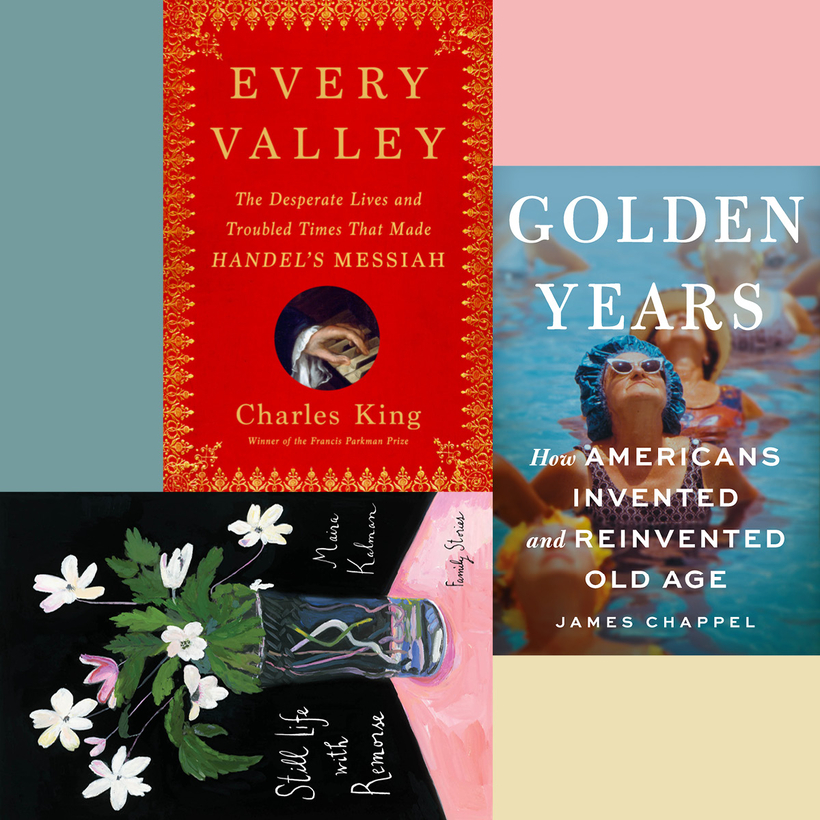

You do not have to be able to carry a tune to take part in the chorus for Handel’s Messiah, as countless sing-alongs around the world this time of year prove. It may well be, as Charles King writes, “the greatest piece of participatory art ever created,” but almost as miraculous as the composition itself is the way it was created. Handel had seen better days when he started work on it, in 1741, relying on a selection of scriptural quotations put together by a wealthy misanthrope. Handel himself performed the oratorio 36 times, and its popularity was due in large part to the composer’s agreeing to hold an annual concert featuring his work to benefit a charity for needy children.

King does an enthralling job orchestrating all the characters and the political atmosphere that propelled Messiah to such contemporary renown. It remains a minor mystery why Messiah, about the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus and written for Easter time, has become such a Christmas staple, but let’s be thankful the “Hallelujah” chorus elevates a holiday that has become so shamelessly commercial.