Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time is enormous. About 3,200 pages in most English translations. The book is acclaimed as “the world’s longest novel” by Guinness World Records, its authors lauding its “9,609,000 characters”. (“Each letter counts as one character. Spaces are also counted.”) If the serious reader is liable to fret that the accolade is a doubtful one — the literary equivalent of “world’s fattest man” — the frisson of a challenge is not easy to ignore either.

To the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik, In Search of Lost Time is “Mount Proust”. The ascent is the final test of bookish endurance. “9,609,000 characters? Bring it on.” Or so I muttered to myself in the dying days of 2022, contemplating with a mountaineer’s appraising squint the sky-blue and yellow livery of my elegant 12-volume (12!) secondhand edition. One does not casually pick up Proust. One makes a vow, a commitment, a resolution. Proust was my New Year’s resolution.

I read In Search of Lost Time on beaches, on airplanes and on rain-lashed buses toiling through wintry Hackney. I read it in cafés, in the Times canteen and lying prone on my bedroom floor, eyes watering in concentration as I forced myself through another of Madame Verdurin’s 150 page-long salons. Though I cannot be the only reader to have turned the final page of Time Regained with the half-expectation of being led to a podium and sprayed with champagne by bikini-clad women, Proust is not a race, or an endurance challenge for nerds. It is literature. What can you expect to get out of those 3,200 pages?

One does not casually pick up Proust. One makes a vow, a commitment, a resolution.

In a lecture at Cornell University Vladimir Nabokov provided his students with a useful warning: “The matter-of-fact reader will probably conclude that the main action of the book consists of a series of parties.” Not only the matter-of-fact reader. Another of the 20th century’s great novelists, Cormac McCarthy, damned Proust for his triviality and failure to “deal with matters of life and death”. “That’s not literature.” McCarthy is the representative of those who approach Proust with the serious-minded anticipation of improving themes presented with the appropriate authorial fanfare. But In Search of Lost Time lacks many of the distinctive markings by which we have been taught to identify a great novel. Proust is not sentimentally preoccupied with social justice like Dickens, he unfolds no theory of history like Tolstoy, he indulges in no multi-chapter theological wranglings like Dostoyevsky.

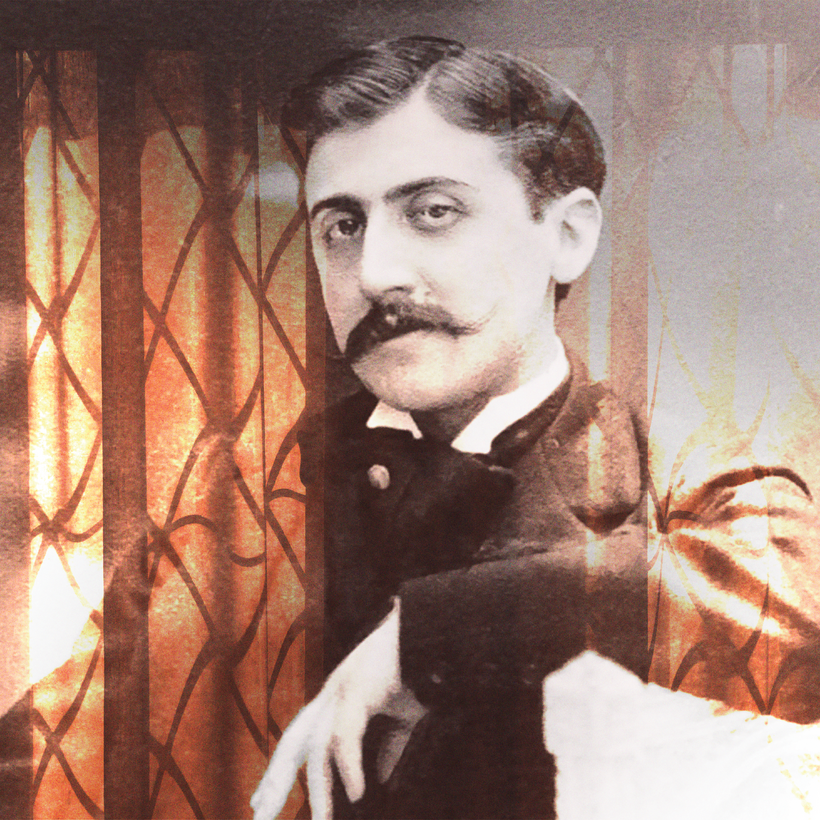

Proust (1871-1922) lived a life derided even by his privileged contemporaries as cosseted and inconsequential. The novel reflects that life. A neurotic, effeminate and snobbish young man attends a lot of high-society parties in fin-de-siècle Paris, pines for the friendship of duchesses (those “queens of society pursuing their course in the heavens at an infinite distance”) and falls in love with a succession of girls whose names (Gilberte, Albertine, Andrée) and sexual habits (prodigious, uninhibited, alfresco) make them sound much more like homosexual men than bourgeois women of the late 19th century — a fact noted by virtually every gay reader since André Gide.

It is not that Proust does not have ideas — his philosophy of time is one of the book’s guiding principles. But I feel that he has the mind of an aphorist, not a theorist. “Grief is as powerful a modifier of reality as intoxication”; “we fall in love for a smile, a look, a shoulder … then, in the long hours of hope or sorrow, we fabricate a person, we compose a character”; “whenever society is momentarily stationary, the people who live in it imagine that no further change will occur, just as, in spite of having witnessed the birth of the telephone, they decline to believe in the airplane.” These observations (the book is full of them) are thoughts, not laws. Their power — like so much else in the novel — derives from their ephemeral brilliance.

Proust knows that the complex, mutable, eccentric stuff of life cannot be crammed into the awkward bulging Christmas stocking of a grand theory like so many walnuts and chocolate coins. People, parties and social relationships must be seen and understood individually and in the moment.

Proust has the mind of an aphorist, not a theorist.

It is a pre-eminently novelistic view of things. Proust is the opposite of the sort of writer who half-wishes his novel was a political manifesto, or a philosophical treatise or a logic puzzle or a collection of essays. He has the novelist’s natural biases in the nth degree: towards individual peculiarity, human psychology, the telling detail, the hidden beauty of the everyday.

In Search of Lost Time is the best butterfly net that has been made for catching fleeing, glittering life. The narrator waits in the drawing room of the girl he loves. The room (in CK Scott Moncrieff’s sometimes over-gorgeous but still unbeaten interwar years translation) “was quite small, empty, its windows beginning to dream already in the blue light of afternoon; I was left alone there in the company of orchids, roses and violets, which, like people who are kept waiting in a room beside you but do not know you, preserved a silence which their individuality as living things made all the more impressive, and received coldly the warmth of a glowing fire of coals, preciously displayed behind a screen of crystal, in a basin of white marble over which it spilled, now and again, its perilous rubies.”

Some readers may wonder whether they can stomach 3,200 pages of this sort of thing. Be reassured that Nabokov (a remarkably useful and skeptical guide to Proust) described only “the first half” of In Search of Lost Time as a masterpiece of 20th-century literature. If you stop at the end of The Guermantes Way you will have had much of what is best in the book: childhood, first love, aristos, duchess-worship. You will avoid being dragged along to the book’s dullest parties and dodge the interminable episode of the narrator’s paranoid imprisonment of his promiscuous lesbian girlfriend, Albertine (more boring than it sounds).

Be reassured that Nabokov (a remarkably useful and skeptical guide to Proust) described only “the first half” of In Search of Lost Time as a masterpiece of 20th-century literature.

You can excerpt no single passage of Proust that unanswerably demonstrates the novel’s profundity. Its power emanates mysteriously out of the accumulation of all those parties, love affairs, sexual assignations, disappointed snobberies and ravishing descriptions of drawing rooms. Through the apparently unending social whirl you begin to perceive that the characters’ lives are altering: powerful men are disappointed, great lovers lose their appetites, the young grow sick and old, and the characters who are already old disappear.

There is a famous scene in which the wealthy socialite and womanizer Charles Swann, whom we first knew one and a half thousand pages previously as the cynosure of fashionable Paris, appears at a party on the point of death. “His face was mottled with tiny spots of Prussian blue, which seemed not to belong to the world of living things, and emitted the sort of odor which, at school, after the experiments, makes it so unpleasant to have to remain in a science classroom.” It is ghastly but unremarkable. A man is dying. But men die. The party flows on. When Swann says he has not got long left to live another character tells him to eat his lunch.

In the final volume, Time Regained, the narrator attends an even more frightening party of old acquaintances whom time has transformed into gargoyles from a picture of Hell by Hieronymus Bosch. One man’s face has acquired “enormous red pockets which prevented him from opening his mouth and his eyes properly”, another is “like one who had come back from dead … so pale, so beaten”. The narrator thinks he hears an old friend and is shocked to find “the voice of my old comrade seemed to have been housed in [a] fat old fellow by means of a mechanical trick”. It is life’s most frightening and most ordinary horror show. “At first it is painful to realize that so much time has passed, afterwards one is surprised it is not more.”

Proust’s parties are profound because parties are full of people, and it is by people and their stories that we register the progress of our lives and the vanishing of the past. What is a human life but an accumulation of incidents that, taken individually, are only fragments of trivial gossip? To say that Proust does not deal with life and death is absurd. The real human truth about life and death is not found in the drama of gory cowboy gunfights but in the disturbing appearance of an old friend in the guise of a ravaged and obese old monster. Suddenly you realize you have been shown the whole of life.

James Marriott is the deputy books editor at The Times of London. He also writes editorials, opinion columns, and features