Hal Ashby’s 1970 directorial debut, The Landlord, begins with a baffling scene, just a few seconds long, featuring none of the characters from the film. We open on a wedding party at the altar as the bride leans over to kiss the best man. Viewers had no way of knowing that this footage came from Hal Ashby’s actual wedding to his (fifth) bride, that the recipient of the smooch was the film’s producer, Norman Jewison, or that the kiss itself was symbolic thanks for launching Ashby’s directorial career.

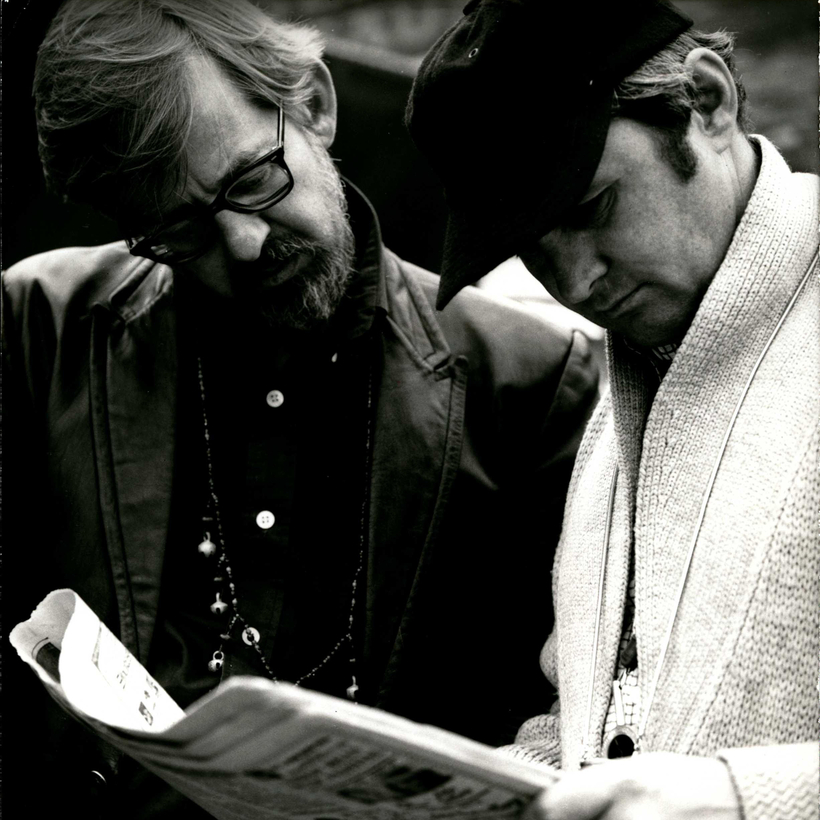

In the late 1960s, Ashby and Jewison were one of the great creative teams in Hollywood. The relationship began with Ashby serving as editor extraordinaire on The Cincinnati Kid and The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming. By In the Heat of the Night, Ashby had ascended to associate producer. By The Thomas Crown Affair, their relationship was almost symbiotic. They were “brothers,” Ashby said. When scheduling issues prevented Jewison from directing The Landlord, adapted from the book by Black American novelist Kristin Hunter, he offered the gig to Ashby.