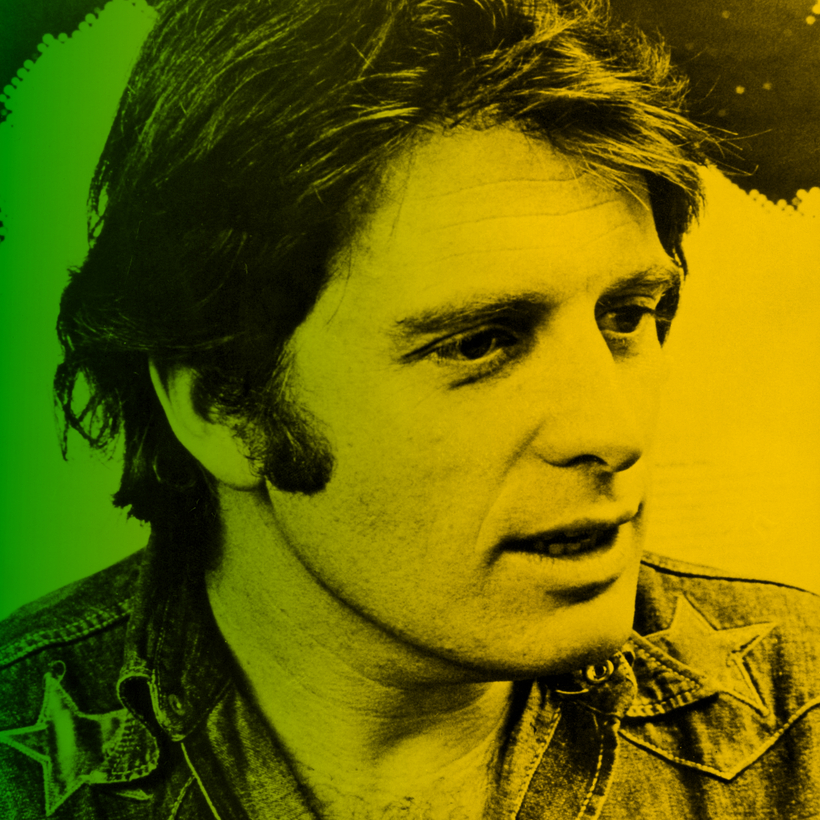

One night in 1958, a 21-year-old Chris Blackwell went with a friend to see the Miles Davis Quintet at Café Bohemia, in Greenwich Village. Afterward, he wrangled his way into a small, smoky backstage room to meet both Davis and John Coltrane. Davis took a liking to the young, white Jamaican, and they began to hang out. One night, watching Blackwell moving his leg unconsciously up and down to music, he scolded him. “Slow down, man. Enjoy it in your head. Keep it to yourself.” Stay cool and be cool—it was a message from the master.

In The Islander, Blackwell (working with journalist Paul Morley) has written a highly entertaining, rapid-fire, hard-to-put-down memoir. The record producer/label founder/hotelier/film producer takes us on a rip-roaring ride through the 60s, 70s, and 80s, the most exciting years in popular music. Davis’s advice to keep cool aligned with the no-worries Jamaican vibe Blackwell was born with. In his approach to both life and business, Chris Blackwell would always manage to stay cool.

Blackwell was a white colonial boy who grew up a hybrid, comfortable in both white and Black worlds. Living with Black people, entranced by Black music, he developed a competitive advantage over other white record executives when Black music began to grow in popularity and, eventually, take over popular culture.

Disclaimer: I’ve known Blackwell for many years and have shared adventures with him. I could be biased. But I think I’m just impressed. This man built an empire in music, expanded into all sorts of other venues, and retained not just the respect but the friendship of some of the most important and popular musicians of our time. Bob Marley, Steve Winwood, Jimmy Cliff, Cat Stevens, Nick Drake, Tom Waits, and U2 are just the top line of artists Blackwell worked with during the height of their success. He’s probably best known as the man who brought reggae to the world, starting with his genius move to market the charismatic Marley as a rock star.

The Islander is packed with juicy stories about the rise of rock music in the 60s and 70s, when the culture seemed to take direction from the radio. Blackwell had a great talent for being everywhere at the right time. You never know who is going to pop up.

In one early chapter, he argues with a long-haired teenage clerk in a London record store over obscure R&B records. It’s Brian Jones, and Blackwell goes to see his group, the Rolling Stones. He is impressed. Seven years later, when his friend Mick Jagger asks if Island would be interested in signing the Rolling Stones, now the biggest band in the world, Blackwell demurs. He doesn’t want Island Records to have an act that is bigger than the label.

He likes to keep everything cool.

Rebel Music

Blackwell was born in 1937. His parents moved from England to Jamaica when he was six months old. There, his mother Blanche Lindo’s family was the aristocratic “first family of rum.”

As an only child on his family’s estate, outside Kingston, young Chris spent most of his time with the 15 Black staff members, who taught him the ways of the other Jamaica. At 18, Blackwell had a transforming experience when his small boat was wrecked on a remote jungle-lined beach and his life was saved by a Rastafarian, a member of a Jamaican cult who were said to be thieves and killers. The incident not only began a connection between Blackwell and the Rastas; it furthered his rejection of the racism that was part of his colonial heritage.

When mismanagement ruined the family rum business, the Lindo-Blackwells found themselves in greatly reduced financial circumstances. Blackwell stepped onto the bottom rung of the music business: servicing jukeboxes all over the country.

From there he began buying hard-to-get R&B records in the U.S. and selling them to Jamaican sound systems—rolling outdoor discos. He was deemed a “selector,” a man who could pick out the best songs and put them in the right order. All of which led to his starting Island Records, initially to record local acts for the Jamaican market.

Chris Blackwell had a great talent for being everywhere at the right time.

He rose from water-ski instructor to music-business mogul in the 60s, the Wild West days of the record industry. Blackwell was an outlier even among the rogues’ gallery of early rock and rhythm-and-blues groups, the man in flip-flops. He started Island in 1959 for $10,000 and made it a reflection of himself, a place for wanderers and misfits. Bono of U2, one of his banner acts, said that, without Island, Blackwell would be “unemployable.”

Blackwell’s story is enhanced by his portrait of the late colonial Jamaica of his youth. Errol Flynn washed up in a storm and stayed. He tried to seduce Blackwell’s mother. Instead, Blackwell got caught bedding Flynn’s girlfriend and Flynn punched him out.

Ian Fleming lived on the north coast at an estate called Goldeneye, writing James Bond novels. He dated Blackwell’s mother, who was the inspiration for Pussy Galore in Goldfinger. Blackwell grew up around Fleming, Flynn, and neighbor Noël Coward. He was hired as a location scout for Dr. No, the first Bond film. When he became wealthy, he bought Goldeneye and restored it to its early glory.

At a time when successful entrepreneurs often seem to be socially inept and psychologically damaged, Blackwell’s story puts us in the company of a businessman who was as ethical as he was fun and strong-willed. He also has incredibly good taste. As the decades rolled by, he sold Island to Polygram and moved into real-estate development, hotels, and movies.

The book focuses almost entirely on his musical adventures, touching just lightly on his pioneering work in the hospitality business, as a first mover in the rebirth of South Beach and, then, his last act—a return to his beloved Jamaica, where he founded a high-end, idiosyncratic luxury-hotel group, Island Outpost. Goldeneye is its centerpiece.

Blackwell now lives like a barefoot prince in Jamaica, overseeing a new rum company that bears his name.

The Islander is 320 pages long. I could have read 320 more.

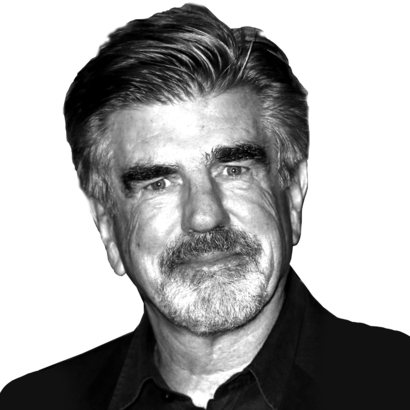

Tom Freston is a media-and-entertainment executive, a co-founder of MTV, and the board chair of the ONE Campaign, an anti-poverty organization