A prince in exile. A German model. A shot in the dark. An unstoppable chain of events that, after the death of a teenager, would forever entwine the lives of strangers.

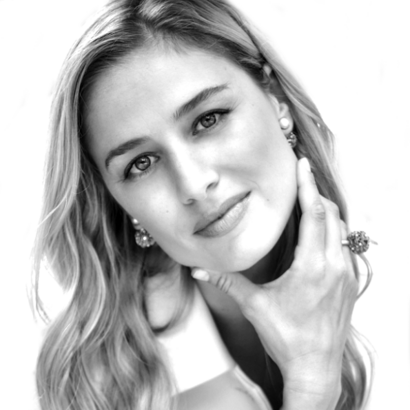

The King Who Never Was, a three-episode documentary series that I directed and co-produced for Netflix, tells the story of Italy’s last heir to the throne, Vittorio Emanuele di Savoia, and that of Birgit Hamer, a German model who was convinced that Vittorio Emanuele shot and killed her younger brother Dirk and fought for decades to bring the prince to justice.