“I could have managed my life in a better way,” Whitney Tower Jr. concedes.

Tower is a descendant of both Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of America’s greatest money magicians, and William Collins Whitney, a Gilded Age prince who, though he never rolled in it the way the Commodore did, made a respectable fortune in streetcars.

Yet Tower has mixed feelings about his ancestry. For one thing, much of his family is nuts. He points to his great-uncle Payne Whitney, who was so disturbed by the neurotic tendencies in his bloodlines that he concluded that “his relatives were crazy enough to need their own mental institution.”

The result was the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic, in Manhattan. “I can’t believe we don’t have family reunions there,” Tower tells Michael Gross, who spoke to him in West Palm Beach while doing fieldwork for his latest book, Flight of the WASP, in which he sheds light on why America’s old ruling class produced so many basket cases.

Sitting in his wheelchair in Florida, Tower recalls the old Whitney homestead on Long Island. At its zenith, the estate comprised 800 acres and a mock-French château. It was sold for development in the 1950s, when Tower was seven. In 1961 his grandfather Roderick Tower committed suicide in Locust Valley, and a short time later he himself was dispatched to boarding school, where he “learned to drink.” After his expulsion, he was sent to public school in Westchester, where he “graduated to drugs.”

In his prime, Tower “chased the dragon” in Bangkok, and on returning to America “shot up at a family funeral” during which he asked Nancy Reagan why she urged people to “just say no” to drugs. He partied with Mick Jagger and mocked the midnight bell at Xenon, but as he reflects on his life, he is struck by the “irony of his wasted advantages.”

Even in his sere and broken state, the result of half a century’s worth of overindulgence in “alcohol, pot, cocaine, heroin,” Tower can’t forget that he was raised “to be superior.”

It is the plight of the WASP, a doomed figure who not only can’t live up to ancestral expectations of superiority but doesn’t really want to. Henry Adams wrote The Education of Henry Adams to try, and fail, to come to terms with the problem. When, as a boy, he was forced to help correct proofs of his ancestor John Adams’s prose, he vowed that “if he ever grew up to write dull discussions in the newspapers,” he would “try to be dull in some different way from that of his great-grandfather.”

And John Adams was the presidential ancestor Henry disliked least. He thought the other one, John Quincy Adams, a shit.

Whitney Tower Jr. has mixed feelings about his ancestry. For one thing, much of his family is nuts.

Gross finds the source of the pathology that afflicted Tower no less than Henry Adams in the mundaneness of the WASP mind itself. He begins Flight of the WASP with William Bradford, the pious Pilgrim who doubled as America’s original climber. Disembarking from the Mayflower in 1620, he aspired to found a new Zion in the wilderness. When that plan failed, he contented himself instead with amassing “the largest estate Plymouth had seen to that time.”

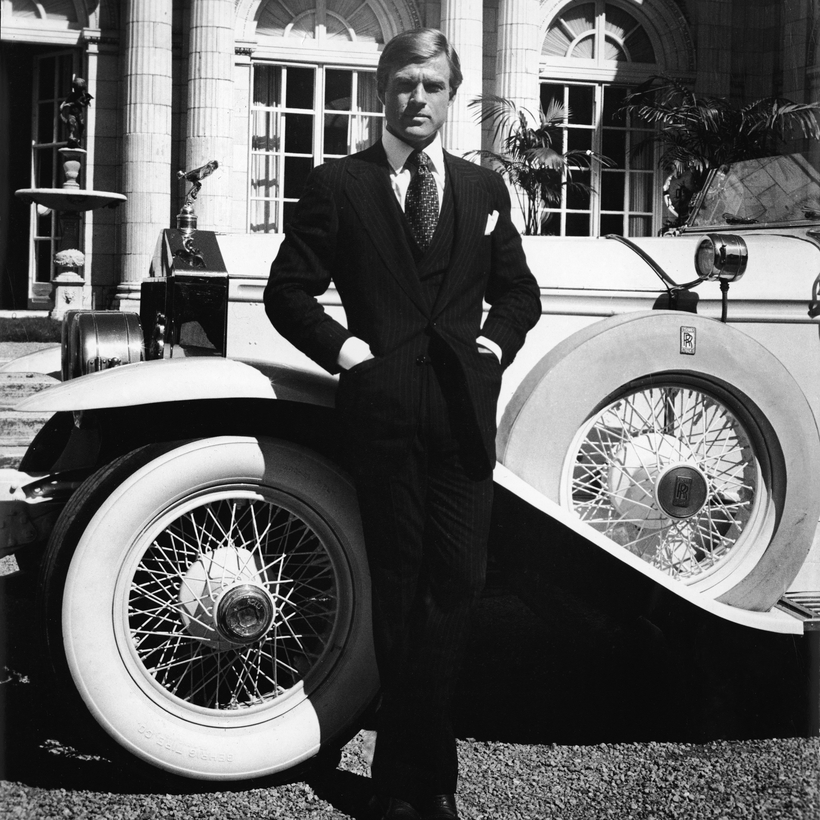

Bradford’s example of chucking high, vaguely poetic ideals for mere money hustling would soon recommend itself to other WASPs, as well as to most of the rest of the citizenry. Scott Fitzgerald, before he settled on the title The Great Gatsby for his novel, thought to call it Trimalchio in West Egg, as he winked at the vulgarities of James Gatz. But for Fitzgerald’s readers, the gaudy, non-U manners of Gatz (or Gatsby, as he re-christened himself) were the stigmata of an American saint, one whose salvation depended on his his embracing tackiness as a vocation.

At the height of the Gilded Age, William Collins Whitney—Whitney Tower Jr.’s great-great-grandfather—promised to break the philistine mold and show that America could be something more than a gigantic shopping mall. He seemed capable of it; he was very much the Yale man, the Skull and Bones man, with a winning way about him.

Only he couldn’t go through with it. The extent of his financial malfeasance will never be known, so intricate was the web he wove: but his extravagance rivaled that of the most garish figures of the age. His apologists try to explain his proto-Trumpian style as the lavishness of a Medici prince, but unlike the Medicis, Whitney patronized very few artists, and his taste was hideous.

In his prime, Tower “chased the dragon” in Bangkok, and on returning to America “shot up at a family funeral” during which he asked Nancy Reagan why she urged people to “just say no” to drugs.

The deeper difficulty, Gross shows in Flight of the WASP, is that high-minded WASPs—the genteel humanists with inherited incomes who sought a middle way between commerce and Kultur—were as limited as their brothers the stockjobbers. The Adamses, according to Henry, looked down on Boston’s State Street bankers, for the Adamses were superior persons who had read Tacitus, and who pursued public virtue after the high Roman fashion.

It was Santayana who pointed out that this genteel tradition was more deadly to the soul than barbarism itself.

Penelope Tree, another of Gross’s informants, traversed that genteel hell. Her pedigree is crowded with the great and the good of New England Brahminism—Endicotts, Peabodys, Parkmans, Cabots. Yet she grew up, she tells Gross, “in benign neglect.”

Or not so benign. Penelope’s mother, Marietta Peabody Tree, rebelled against caste expectations, divorcing C.I.A. spymaster Desmond FitzGerald to marry Ronald Tree, the Marshall Field heir, before having a walkout with Adlai Stevenson while Ronald was still living. Yet Marietta, blithe spirit though she was, insisted on subjecting Penelope to the same “joyless, punitive” upbringing that she herself had suffered—the way of the WASP.

While Marietta jetted frenetically between New York and Barbados, Washington and London, with Adlai, until the poor man dropped dead before her eyes in Grosvenor Square, she sent Penelope, a teenage habitué of Manhattan nightclubs, to a “strict all-girls Massachusetts prep school,” where she succumbed to anorexia.

Then, as if by a miracle, Penelope caught the eye of Richard Avedon. The occasion was the ball Truman Capote threw for Kay Graham to mark her emergence from mourning her husband, Phil Graham, after his suicide. Avedon promptly placed Penelope before his camera, but the “nonstop party,” obligatory for newly discovered fashion models, took its toll, and she soon found herself in the same pit into which Whitney Tower had fallen. “I started taking too many drugs,” Penelope tells Gross, and though she turned to Jung, to Buddha, and to a drummer in a surf-rock band, transcendence eluded her.

American Dreaming

Ralph Waldo Emerson believed that the defect of New England Yankeeism, the culture that gestated so many WASP pathologies, lay in its “near-sighted” vision. He deplored the shallow “materialized intellect” of Boston and New York elites; having never got beyond the “practical common-sense of modern society,” they never saw “the moon with all the muses at midnight.”

With inherited money to fall back on, Emerson could afford to dismiss “practical common-sense” and instead compose sentences about seeing “the moon with all the muses at midnight.” But he was onto something when he saw that Americans have difficulty externalizing their dreams. Virtually all pre-modern peoples, he knew, embodied their night visions in waking life in the transfigured form we call art: some, such as the Venetians, went so far as to make their habitats resemble living dreams.

Neurasthenic WASPs like Henry Adams and Isabella Stewart Gardner, oppressed by America’s banality in the Brown Decades after the Civil War, followed Emerson’s lead. They seized on the old cathartic, dream-driven arrangements they found in Venice and Athens and attempted to reproduce them in the museums, concert halls, and college humanities programs they lavishly endowed back home.

It was a bit cracked. When hysterics seek their own cures, they come up with things like humanities programs. But if WASP humanists failed to redress imbalances in the American psyche, their aspiration survived in the boomer WASPs of the Age of Aquarius, who looked to the madder music and stronger wine of the 1960s to regenerate the republic’s dream infrastructure.

Gross notes that it was a WASP, Michael Butler, who brought the country Hair; surely naked hippies singing “Good Morning Starshine” would get Americans out of their funk and in touch with their dreaming souls. Yet, oddly enough, the preppy flower children’s mock-ashram style proved as ineffectual, as a form of mental hygiene, as the mock-Venetian style of their ancestors.

Gross closes his illuminating history in the twilight of the WASP ascendancy, when hysterias that were once the luxury of the few pervaded the lives of the many. It is the virtue of his book that it brings the now defunct patricians to life in all their doubleness, begetters of American prosperities who drove themselves crazy trying to heal American hysterias.

Michael Knox Beran is the author of several books, including The Last Patrician: Bobby Kennedy and the End of American Aristocracy and, most recently, WASPs: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy