Historians of the golden era of Himalayan mountaineering credit its triumphs to the use of bottled oxygen to overcome the thin air of the “death zone” above 25,000ft.

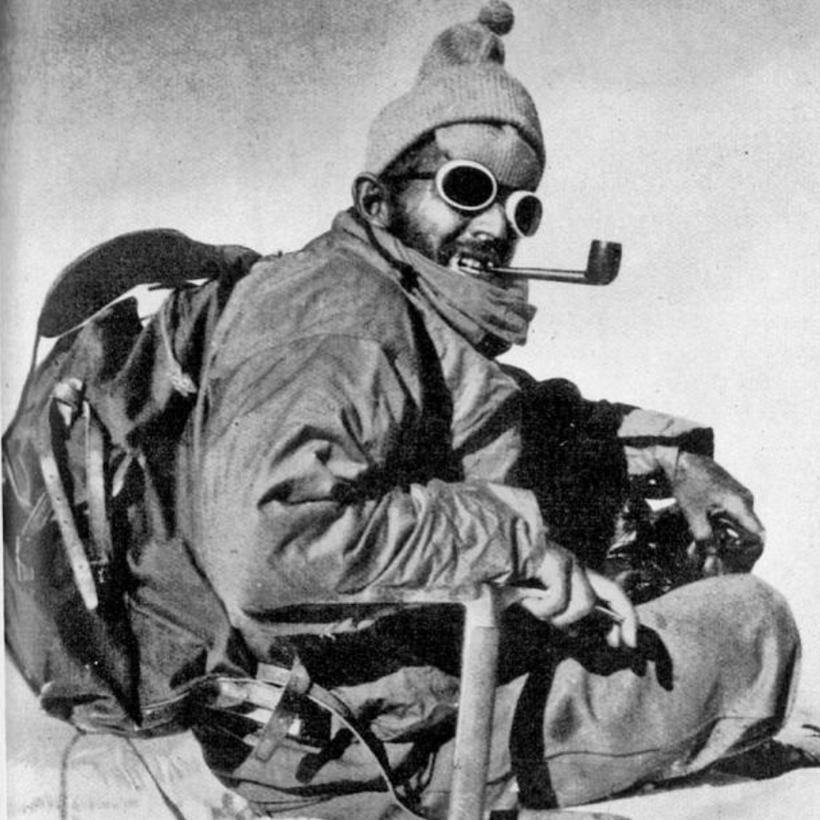

Perhaps they should have paid more attention to the expedition records, which reveal a little-known fact: many of our greatest climbers were not so much gasping for air as gagging for a cigarette. Packed in with mountaineering equipment such as ice axes and ropes, the records show, were truly heroic supplies for the smokers.