1.

Horsing Around

Konik horses tussle in a field

2.

Gaga for Goo-Goo

Researchers discover that baby talk is the universal language

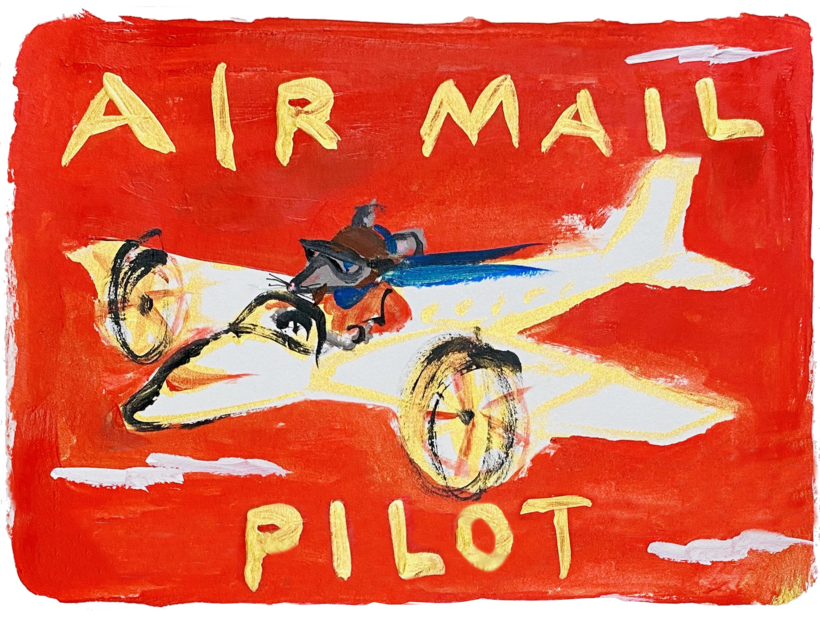

As Air Mail Pilot readers are only too well aware, adults do many things that are incomprehensible. One of those things is how they talk to babies.

Surely you’ve heard it, if not experienced it yourself in distant memory, the way adult voices get all high-pitched and coo-y when addressing infants: Awwww! Wook at that widdle sweeeeetie piiiiiiiie!