Trunk Show

Veggie Tales

Once upon a time, there was a thing called the Oscars, an awards show for movies that people used to care about. Your parents might remember it. But the American Library Association (A.L.A.) Awards for children’s literature are still a big deal, and this year’s were announced on Monday.

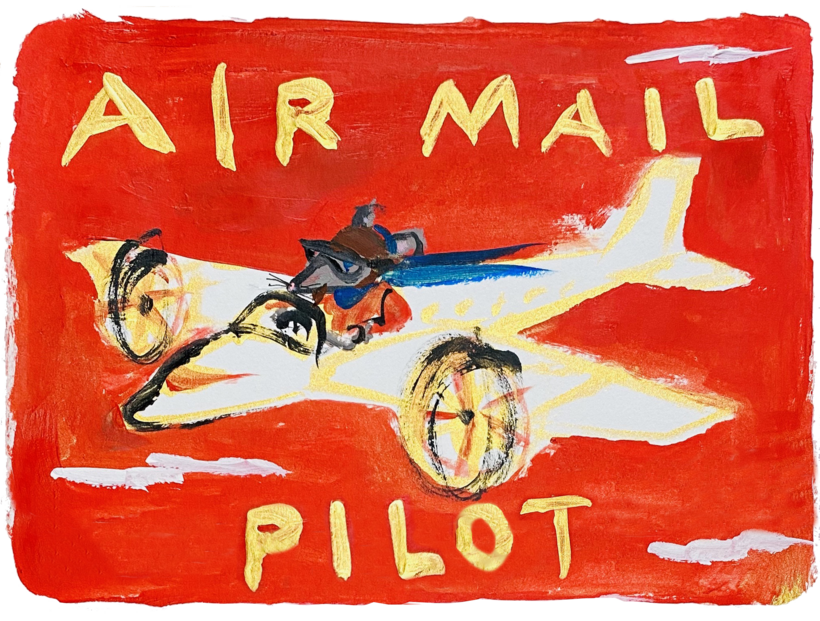

The A.L.A. honors books in all kinds of categories, but Air Mail Pilot is particularly attached to the Randolph Caldecott Medal, which is given each year to “the most distinguished American picture book for children.” Children? No offense, young readers, but Air Mail Pilot firmly believes that picture books are for everyone!