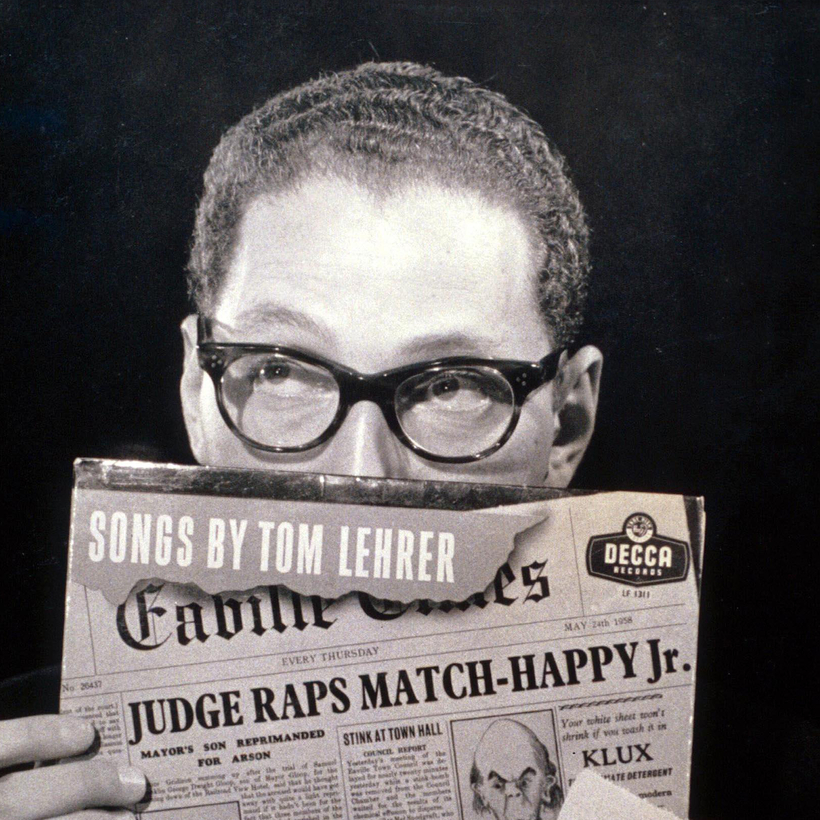

The inimitable Tom Lehrer once told an audience that his ambition was to advance “from adolescence to senility, hoping to bypass maturity.” By all evidence, he had achieved only two-thirds of those goals when he died last week at age 97, his sparkling, subversive wit still intact.

As recently as November 2022, Lehrer posted notice on his bare-bones Web site—tomlehrersongs.com—renouncing copyright for all of his works, and granting permission “to anyone to set any of these lyrics to their own music, or to set any of this music to their own lyrics, and to publish or perform their parodies or distortions of these songs without payment or fear of legal action.” But he warned: “THIS WEBSITE WILL BE TAKEN DOWN AT SOME DATE IN THE NOT TOO DISTANT FUTURE, SO IF YOU WANT TO DOWNLOAD ANYTHING, DON’T WAIT TOO LONG.”