A man who was older and in a position of power once said to me, “I feel sad for you. You’ve already been the most beautiful you will ever be, and now you have to spend the rest of your life watching your beauty fade.” I was just 30. I found a dermatologist, got Botox. “At your age,” this doctor told me, “it’s preventative.” The message was clear: Render your face immovable—lifeless!—and avert the crisis of aging.

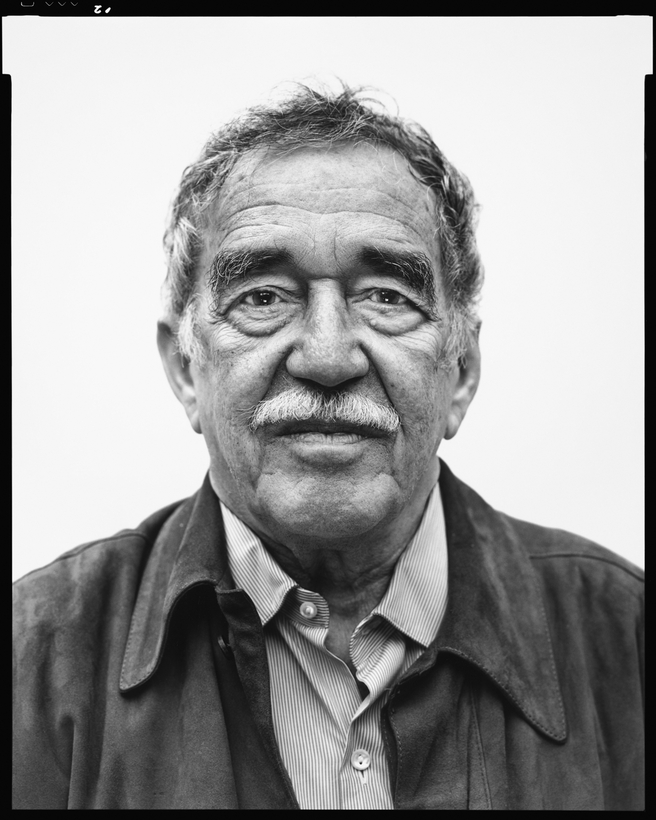

Next Thursday, a commanding meditation on that crisis, “Richard Avedon: Immortal,” opens at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Subtitled “Portraits of Aging, 1951–2004,” it features nearly 100 photographs that dramatize our universal mortality. Considered scandalous when Avedon began taking them, in the early 50s, the portraits struck many critics as “attention-grabbing,” a photographic “revenge” against his celebrated subjects or an act of penance for his early work in fashion, where youth and beauty reign.