That bad, bad time, exacerbated by the lawsuit McCartney filed on December 31, 1970, after John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr appointed the mob-boss-like New York accountant Allen Klein as the Beatles’ manager, led to McCartney’s remarkable second act. He was in bed one night with his American wife, Linda, having escaped London for a remote three-bedroom farmhouse in Campbeltown, Scotland, when Johnny Cash came on the television, playing with some country musicians he had never heard of. “I thought, here’s Johnny, he’s doing it. So I turned to Linda and said, ‘Do you want to form a band?’ And she went, ‘Sure.’”

So begins the story of Man on the Run, Morgan Neville’s film about McCartney’s post-Beatles life. Neville is adept at tales of adversity — his 2013 documentary 20 Feet from Stardom follows the backing singers whose job it is to make the stars sound good — and the film is really a tale of going back to basics, from fixing up a tumbledown cottage in Scotland to starting a new band from scratch, not easy when you’re the most famous musician in the world. As Mick Jagger says: “I’m not very good at fixing roofs, so I can’t really relate. But he wanted to be grounded in an ordinary life because the Beatles were free of any grounding.”

Neville says: “The film begins on the day the Beatles break up and it ends on the day John Lennon dies. Those were the seismic events that changed Paul’s life. The key that unlocked the whole film was quotes Paul gave to the press for the release of [his debut solo album] McCartney in 1970. The last question is, ‘What are you going to do now that you’re not a Beatle?’ The answer is, ‘I’m going to try and grow up.’ That was our story. How do you grow up, find a normal life, after having lived in outer space?”

Man on the Run works because, despite McCartney’s official endorsement, the film isn’t a hagiography. It’s a portrait of a normal man in abnormal circumstances, working it out as he goes along. Included is an admission of the “two months of boozing” he indulged in during his lowest ebb. “John broke up the Beatles, but I got the rap… that’s a bit of a weight to bear,” he says at one point, still sounding hurt.

There are testimonies on the less than generous wages doled out to various members of Wings, with the original drummer Denny Seiwell complaining of “living on a meagre retainer” despite playing behind a Beatle each night. “We worked for 70 quid a week,” Seiwell told Tom Doyle for his 2013 book Man on the Run: Paul McCartney in the 70s, on why he quit the band in 1973. “But I was making two thousand a week in New York as a session guy.” It makes you wonder what McCartney had to say about it all.

“John broke up the Beatles, but I got the rap… that’s a bit of a weight to bear.”

“This film is 100 per cent my film,” Neville asserts. “There is not a single edit that has anything to do with Paul or his representatives. I know it made him uncomfortable at times, but he was smart enough to allow me to present my version of the story.”

There are also revelations, like the time McCartney almost drowned after jumping off some rocks in Hawaii in 1975, the whole near-death experience captured on home movie footage. Was the man Neville dealt with much the same as the Macca we all think we know?

“There’s a line in the film, ‘I don’t have to be that Paul McCartney guy any more,’” Neville says by way of answer. “He has always been aware of his persona. And Paul can be tough, which he doesn’t necessarily show. You don’t become that successful without a fair amount of grit and drive.”

In a sense the film is simply about starting a band from scratch. “After the end of the Beatles I was faced with certain alternatives,” McCartney told me. “One was to give up music entirely and do God knows what. Another was to start a super-band with very famous people, Eric Clapton and so on. I didn’t like either, so I thought, how did the Beatles start? It was a bunch of mates who didn’t know what they were doing. That’s when I realized: maybe there is a third alternative. To get a band that isn’t massively famous, to not worry if we don’t know what we’re doing because we would form our character by learning along the way. It was a real act of faith. It was crazy, actually.”

Neville believes the success of the Get Back documentary series helped McCartney to open up about the worst period of his life. While Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 1970 documentary Let It Be cast the end of the Beatles as a terrible time, Peter Jackson’s three-parter showed that it wasn’t all bad. ”Get Back allowed Paul to forgive himself, because just from reading the reviews from the time and learning how people criticized everything he did, you can see why it was hard.”

He’s not wrong. As Lennon and Harrison’s early solo careers flourished, McCartney’s was blasted. Rolling Stone magazine went so far as to castigate the 1971 album Ram as “the nadir in the decomposition of rock so far”. I ask Neville how he thinks McCartney dealt with it, alongside the alienation from the friends with whom he had gone on the Beatles’ amazing journey.

“Scotland became his fortress of solitude,” he replies. “To this day he can still get riled up about those awful meetings with Allen Klein, which is why escaping to the farmhouse meant everything to him. There’s a line in the film where his daughter Stella says, ‘For all of us, that was the happiest time in our lives.’ Even when they moved to the south of England, the house wasn’t very big. He always wanted the family to be together.”

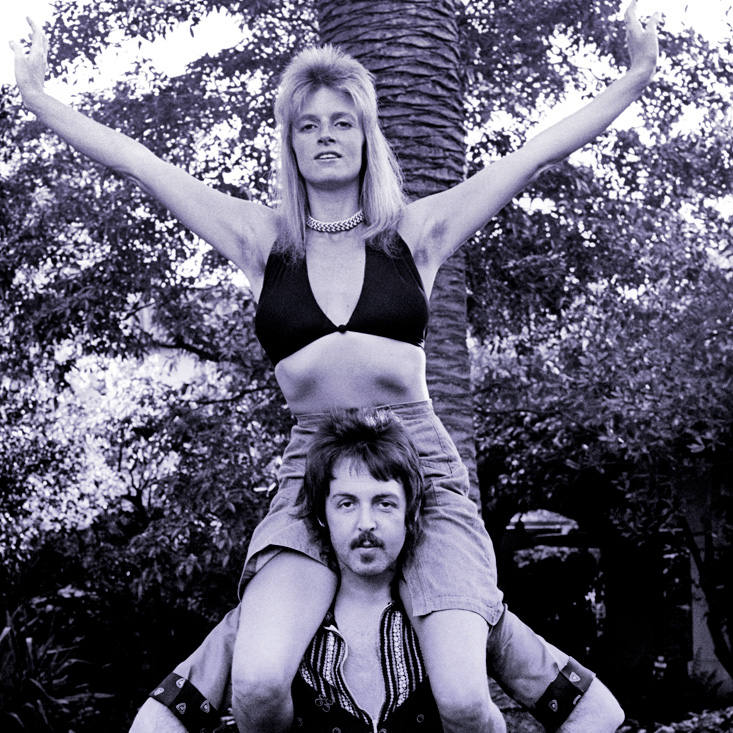

That included bringing in the wife on keyboards. “Getting Linda in the group, the attitude was: you’re crazy,” McCartney says. “But I wasn’t motivated by having a fabulous group. I was motivated by not wanting to leave my wife behind. We had only just married. What was I going to do, run off on the road? The Beatles weren’t very good when they started out either. The Beatles never won a talent contest in their lives.”

Linda McCartney, who died in April 1998, is the missing figure in Neville’s film. “Linda was incredibly strong,” the director says. “She had great taste in music, she’d had a whole career in the rock world [as a photographer], and she was his anchor. She was the person who kept the outside world at bay and let Paul be whoever he wanted to be.”

McCartney’s back-to-basics approach meant touring with Wings in an old van and charging 50p for concerts, but as the drummer Geoff Britton says in an interview from 1974: “He wants you to be all normal and equal. You ain’t normal and equal because he’s a world superstar and you’re a dog-faced nobody.” When asked to respond to accusations of meagre wages from former band members, McCartney explains that he hadn’t dealt with cash since his teens so he had no idea about it. That was a manager’s job.

“Paul says they didn’t confront him about it,” Neville adds. “They would have confronted a manager, but there was no manager, and this is Paul McCartney, who wouldn’t have been easy to ask for more money. It created a lot of resentment that was never articulated.”

Man on the Run also covers McCartney’s questionable lapses of taste. Once derided albums like McCartney and Ram may now be hailed as classics, but the 1973 TV special James Paul McCartney, with its Busby Berkeley dance routines and pub singalongs, does not demand repeat viewing and nobody is hailing the Wings version of Mary Had a Little Lamb as a misunderstood masterpiece. What happened there?

“Basically, he was living with children,” Neville says. “He sang Mary Had a Little Lamb to his daughter Mary. A manager would have talked him out of recording it, but whenever he asked Linda if he should do something she’d say, ‘It’s allowed.’ Paul’s creative instincts had served him so well, for so long, he didn’t want to doubt them.”

Those creative instincts led to such brave, brilliant moments as the 1973 album Band on the Run. After being busted for growing marijuana on the farm — “we planted ten and five came up illegal” — McCartney had the idea of rock stars as outlaws on the lam from the law, record labels, everyone. The album was recorded in Nigeria after McCartney ignored advice from EMI’s chairman Len Wood not to go there because of a cholera outbreak. Seiwell and the guitarist Henry McCullough quit days before they were due to fly out, leaving the McCartneys and Denny Laine to arrive in Lagos in monsoon season and discover a flooded, half-built studio. It got worse from there.

Paul and Linda were mugged at knifepoint while walking back to their villa one night, inspiring Linda’s immortal line: “Don’t touch him, he’s a musician!” Yet despite, or perhaps because of, such challenges, Band on the Run became McCartney’s first truly great album of the post-Beatles era, going to No 1 on both sides of the Atlantic. “Jet,” “Let Me Roll It” and the title song remain highlights of a McCartney concert to this day, and as he says: “The success of Band on the Run gave us confidence, especially Linda. Instead of being made fun of because of her lack of expertise, she was getting respected.”

There is another side to Paul McCartney explored in the film. If you tell him not to do something, he’s more likely to do it. Like bringing marijuana into Japan on January 16, 1980.

“I found footage of the bag of marijuana. It is sizeable,” says Neville, underplaying the fact that there was enough grass in that bag to keep a stadium’s worth of Grateful Dead fans happy. “Paul was looking at a seven-year sentence, and they were thinking about getting a house outside Tokyo so Linda could raise the children there. But throngs of McCartney fans outside the jail made it embarrassing for the Japanese government, so it was easier for them to claim Paul never officially entered the country. They said they hadn’t stamped his passport.”

The marijuana incident led to an awkward moment for Neville during a private screening of Man on the Run. “One of the grandchildren said, ‘Grandpa went to jail?’ I guess it wasn’t discussed at family gatherings.”

Wings broke up in 1981, with Laine feeling he wasn’t adequately compensated for the loss of touring income from the arrest, but after Lennon was shot on December 8, 1980, McCartney was ready to call it quits anyway. “The plan was: we’ll start from rock bottom, the kids will come with us, we’ll be a family and we’ll go through the tribulations together. I suppose because we couldn’t think of anything else to do.”

Ultimately, Man on the Run is a film about prioritizing family over career, of moving on when others want you to do the same thing; themes we can all relate to. “The film captures a time when Paul was carefree and creative in a way we don’t often see in rock stars,” Neville concludes. “Everything about Paul in the Seventies was handmade. Wings was like something you made on the kitchen table.”

Therein lies the eternal charm of Paul McCartney. He may have been a Beatle, but to borrow a line from Nowhere Man, he’s a bit like you and me.

Paul McCartney: Man on the Run is in cinemas now and will stream on Prime Video beginning February 27

Will Hodgkinson is the chief rock-and-pop critic at The Times of London