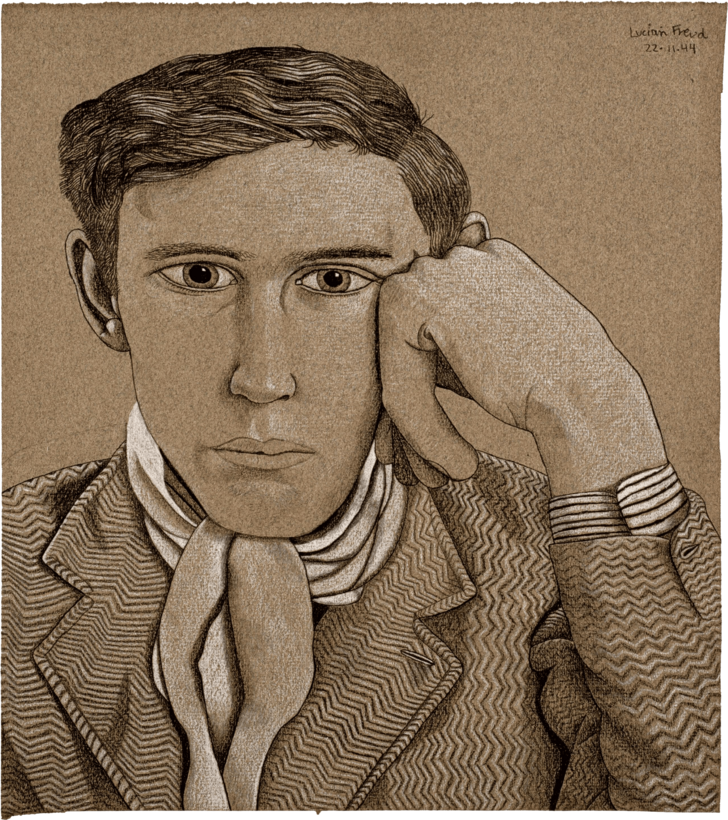

Four years after Lucian Freud’s death, in 2011, his childhood artworks, letters, and sketchbooks, filled with hundreds of drawings, were given to the British government in lieu of death duties, and the Lucian Freud Archive at the National Portrait Gallery was born. This collection provides the foundation of the exhibition “Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting,” which has just opened at the gallery. Here, we can follow Freud’s artistic journey from the brightly colored sketches of a little boy who invented a “zebra unicorn” as a dream pony to the towering figure of 20th-century British art, whose work radiates postwar ennui with a limited “Londony” palette.

“What makes this exhibition so interesting,” says Sarah Howgate, who organized the show and is the senior curator of contemporary collections at the N.P.G., “is how Freud’s work changed. At the beginning, his paintings were more like drawings. Ultimately, his drawings became like paintings. He drew all the time, even after the focus of his work shifted to painting. Sometimes he sketched his own paintings, as with After Watteau, a work in which he was emotionally invested. The sketch was an aide-mémoire.” The final expression of such memory-making is embodied in Freud’s etchings, a practice explored in the final room.