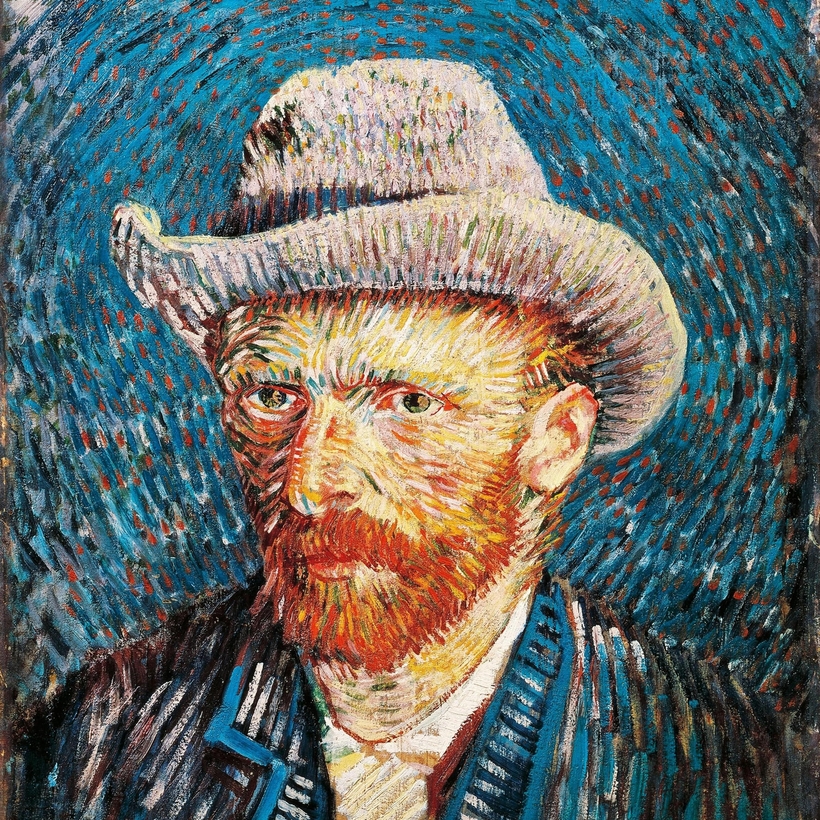

Irv Arenberg, an 85-year-old retired ear surgeon, lives in Arizona and counts among his patients the late artist Vincent van Gogh. Arenberg was a teenager when he first encountered Van Gogh, in the guise of the 1956 biopic Lust for Life, and he became fascinated by the Dutch artist, whom he gradually got to know through undergrad art-history classes and the posters he hung in his dorm room.

In 1990, after years of practicing medicine and reviewing Van Gogh’s case history via his hundreds of letters, Arenberg published a paper in JAMA diagnosing Van Gogh as suffering not from epilepsy, as the artist’s physician claimed a century earlier, but from Ménière’s disease, an inner-ear affliction that can cause vertigo, of which Van Gogh complained, and tinnitus, a persistent ringing in the ears. Ménière’s, to Arenberg, could better explain Van Gogh’s decision to slice off his ear. After retiring, in 2017, Arenberg recommitted himself to studying Van Gogh and became convinced that art historians had made an even more alarming mistake: Van Gogh had not committed suicide. He’d been murdered.