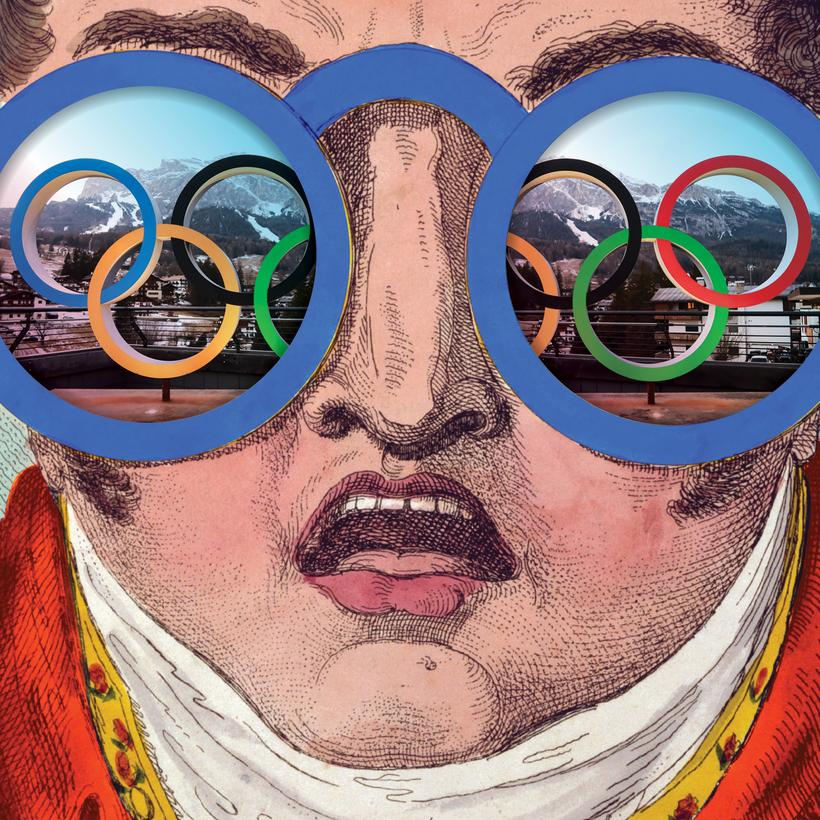

Last week, the population of Cortina d’Ampezzo breathed a collective sigh of relief: snowflakes were finally descending from the gray sky. A little over a week before the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics were set to begin, on February 6, the town was experiencing its first real snowfall of the year: 22 inches’ worth.

By the time the flakes arrived, reports detailed cars stuck on the roads, tires slipping and sliding. A 55-year-old security guard died during an overnight shift at a construction site near Cortina d’Ampezzo’s ice arena as temperatures dropped to 10 degrees. When I asked a Cortina regular if there was any controversy surrounding the Olympics, she said, “Just that it hasn’t snowed.” She called me a couple of days later: “Just that it has.”