Don McCullin has lived several lives in the field of photography, many of them simultaneously. Born in 1935, he grew up in what he called “a constant roundabout of violence,” in the tough Finsbury Park area of London, leaving school (as many did) at 15. In the mid-1950s, McCullin did his national service in the Royal Air Force, where he eventually worked as a photographer’s assistant. He bought a Rolleicord camera and began focusing on what others, he later said, “cannot bear to see.”

The first pictures McCullin took were of hoodlums and down-and-outs, subjects that reflected his own hardscrabble background. He soon moved on to more violent arenas, becoming one of the 20th century’s most renowned combat photographers. Best known for his documentation of the Vietnam War, McCullin also produced work of diamond-hard brilliance and empathy from the Biafra war, Beirut, and the so-called Cyprus crisis in the 1960s.

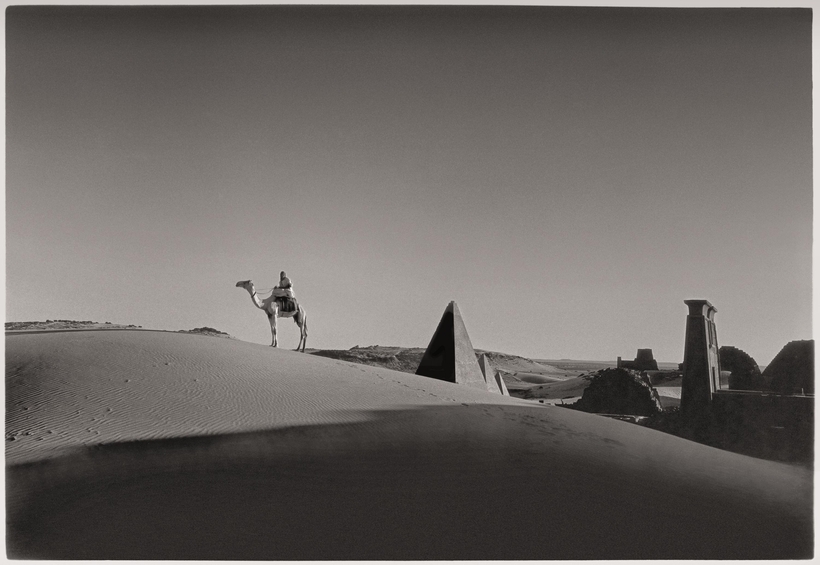

Then came star-snapper status. McCullin took the photographs used in Antonioni’s über-cool Swinging London film Blow-Up, and he was hired by the Beatles for their “Mad Day Out” photo session, in July 1968. After that, McCullin turned to rural landscapes and ancient remains, consciously retreating into nature and the deep past.

It is McCullin’s pictures of classical statuary that are the centerpiece of “Don McCullin: Broken Beauty,” an exhibition that opened yesterday at the Holburne Museum, in Bath, England. Though McCullin collected many of these in The Roman Conceit, a book published last year, a fair number have never been shown in a gallery before. And that’s not all. The exhibition also includes a whistle-stop tour of McCullin’s most indelible images: urban tough guys standing in a bombed-out house (The Guvnors); the extraordinary Goya-esque shot of a gunman sprinting down a Limassol street; the perhaps more extraordinary image of Falangist musicians serenading the corpse of a Palestinian girl in Beirut—the satanic inverse of a Piero della Francesca painting.

“It’s very easy to focus on the gore and the horror,” says the Holburne’s director, Chris Stephens. “But it provides a context for McCullin’s fascination with Roman sculptures. They are wounded and broken and fragmented, but also survivors of 2,000 years of history. There’s something interesting going on psychologically. He’s trying to find solace as a compensation for the awful things that he’s witnessed and recorded.”

McCullin has visited museums in Copenhagen, Tripoli, and New York to photograph statues. Most of them are the relics of grand-tour collectors, pieces that tend to be relegated to the dusty corners of museums—a fragment of a frieze here, the head of an emperor there. In The Roman Conceit, McCullin describes how these objects “consume” him. “I hold in awe,” he writes, “the mouldering stone, the fragments of dreams and the mysteries of the vanquished past. To observe the statues in the silence and stillness of their museum stands gives me solace—they don’t question my conscience or challenge my sense of guilt.”

Having recorded some of the most brutal acts ever committed, McCullin is entitled to brood on issues of guilt. Yet these days, now 90, Sir Don—he was knighted in 2017—cuts a calm, even contented figure. The Holburne is practically in his backyard, given his move in the 1980s to a village near the Somerset town of Shepton Mallet, less than 20 miles away. Still, the scars run deep. “Bearing witness is an important motivation and justification for what he does,” says Stephens. “He doesn’t like to talk about the complexity of his work as an artist. It’s about re-inflicting the pain on the subject each time he prints up the photograph; in the end, in his mind, he’s a photojournalist.”

“Don McCullin: Broken Beauty” is on at the Holburne Museum, in Bath, England, until May 4

Andrew Pulver writes about film for The Guardian and about art for The Art Newspaper. He lives in Oxford