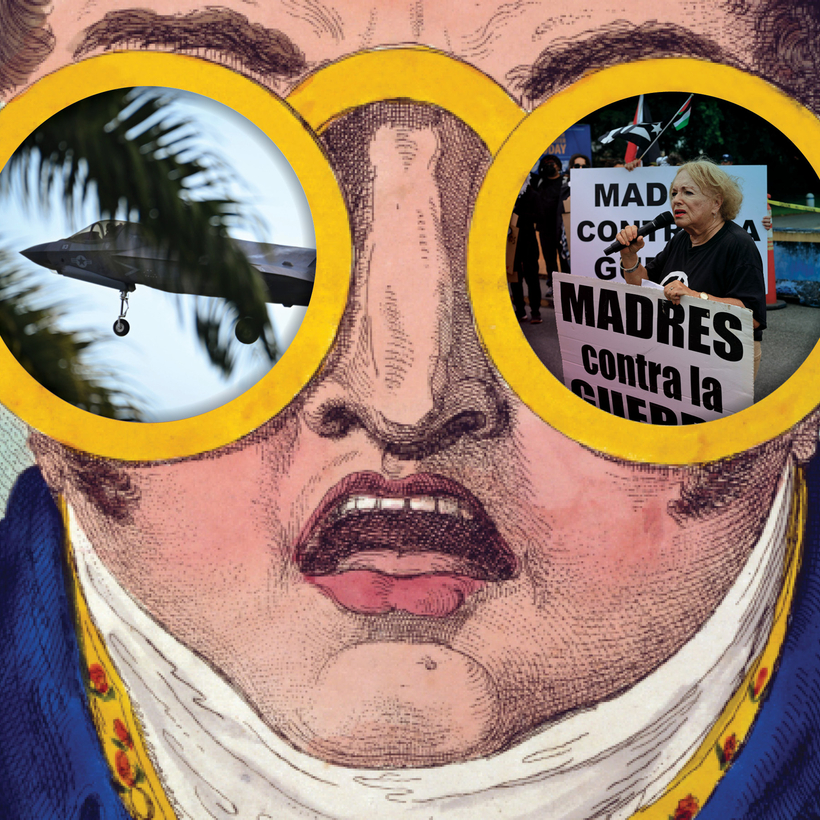

Last week, on his journey to Brooklyn’s Metropolitan Detention Center aboard a Department of Justice Boeing 757, Venezuela’s dictator, Nicolás Maduro, made an unscheduled stop—rumors swirled about a medical emergency—at Ramey Air Force Base, a former U.S. base on the west coast of Puerto Rico.

Although Ramey was officially closed in the 1970s, it—along with the giant Roosevelt Roads Naval Station, on the east coast—has seen a surge in military activity since the fall, reviving both good and bad memories for Puerto Ricans, depending on whom you ask.