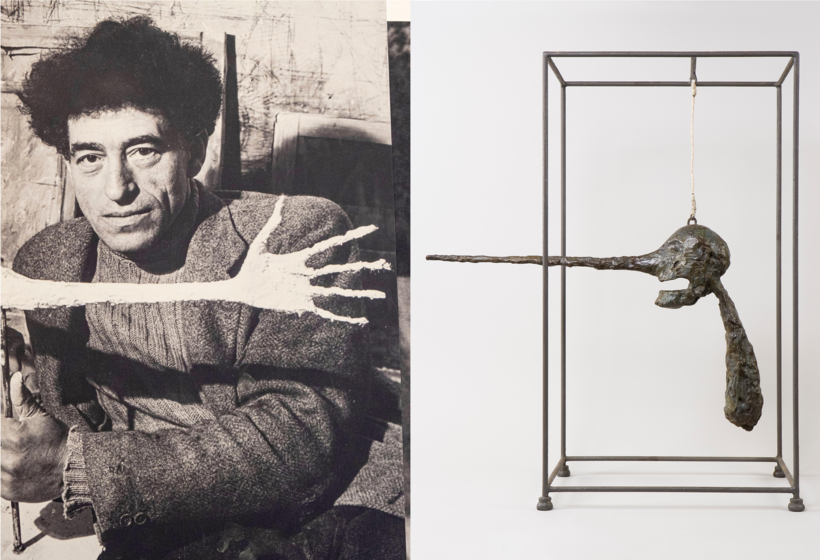

The art of Alberto Giacometti (1901–66)—so profound in its form and provocative in its meaning—continues to influence generations of artists. London’s Barbican Centre explores this legacy in a three-part series of exhibitions that places the work of contemporary sculptors in conversation with the master. The second installment, “Encounters: Giacometti x Mona Hatoum,” opened this week.

Giacometti was born in rural Switzerland. In 1922, he moved to Paris, where he spent the years between 1931 and 1935 as a Surrealist, before returning to the corporeal.

During World War II, he sought refuge in Geneva, where his sculptures, in response to the catastrophes of the conflict, shrank to the size of a matchbox. Then, in 1947, they suddenly became colossal forms, vigorously attenuated into portraits of people at the point of erasure.

Mona Hatoum was born to Palestinian parents in Beirut in 1952. After the Lebanese civil war broke out, in 1975, she was forced into exile in London. Following roughly a decade spent making performance and video art, Hatoum began creating sculptures and installations that turned household items, such as cheese graters and colanders, into objects of revulsion.

Like Giacometti, Hatoum grapples with alienation, displacement, violence, incarceration, and the human condition. “Both Hatoum and Giacometti are preoccupied with distilling the emotional and psychological effects of violence into sculptural forms,” explains Shanay Jhaveri, Barbican’s head of visual arts and the exhibition’s curator. “Their work asks us to reassess our assumed relationships to our surroundings, compelling us to recognize and take cognizance of the disquieting nature of our current reality.”

Hatoum personally selected all 12 Giacometti pieces in the show, mostly from the collection at the Fondation Giacometti, Paris, where she has spent time researching his practice. The first work to confront visitors is Woman with Her Throat Cut (1932), a particularly sadistic bronze of a dismembered mantis, contorted into a pose of postcoital destruction.

Then come pivotal pieces such as The Cat (1951), The Cage (1951), and The Nose (1947). The last consists of a sinister head suspended inside a cage, its snout projecting like a sword beyond the bars and its mouth frozen in an existential scream. For this exhibition, Hatoum has been granted permission to “recontextualize” the renowned work within one of her own.

“Hatoum acknowledges that Giacometti’s use of simple, metal enclosures has been a point of reference for her own work,” adds Jhaveri. “She is interested in challenging the relationships between individuals and systems of control, for which the cage becomes a potent symbol.”

Take Hatoum’s Cube (2006). It’s a cage constructed from bars of wrought iron, interlaced using the same technique as the grills that cover medieval windows. With no entrance or exit, and just too small for a human to stand up in, the enclosure speaks of detention and torture.

Cube is one of 29 Hatoum works on display—among them several new pieces made expressly for the show—which together span 40 years of her career. The exhibition comes to a crescendo with a group of works, says Jhaveri, “that visualize the wide-scale destruction of a world caught up in constant war and unrest.” As Giacometti said, “The form is always in proportion to the obsession.”

“Encounters: Giacometti x Mona Hatoum” will be on at the Barbican Centre, in London, until January 11, 2026

Harry Seymour is a London-based art historian and writer