We’re all familiar with the idea that art imitates life—thank you, Aristotle. But life imitating art is more intriguing. College kids play Quidditch (from Harry Potter), and there are devotees who speak one of the Elvish languages (from The Lord of the Rings). Ordinary people take inspiration from The Scream and American Gothic when they pose for pictures. The entire world these days seems to be a version of 1984 and Wag the Dog.

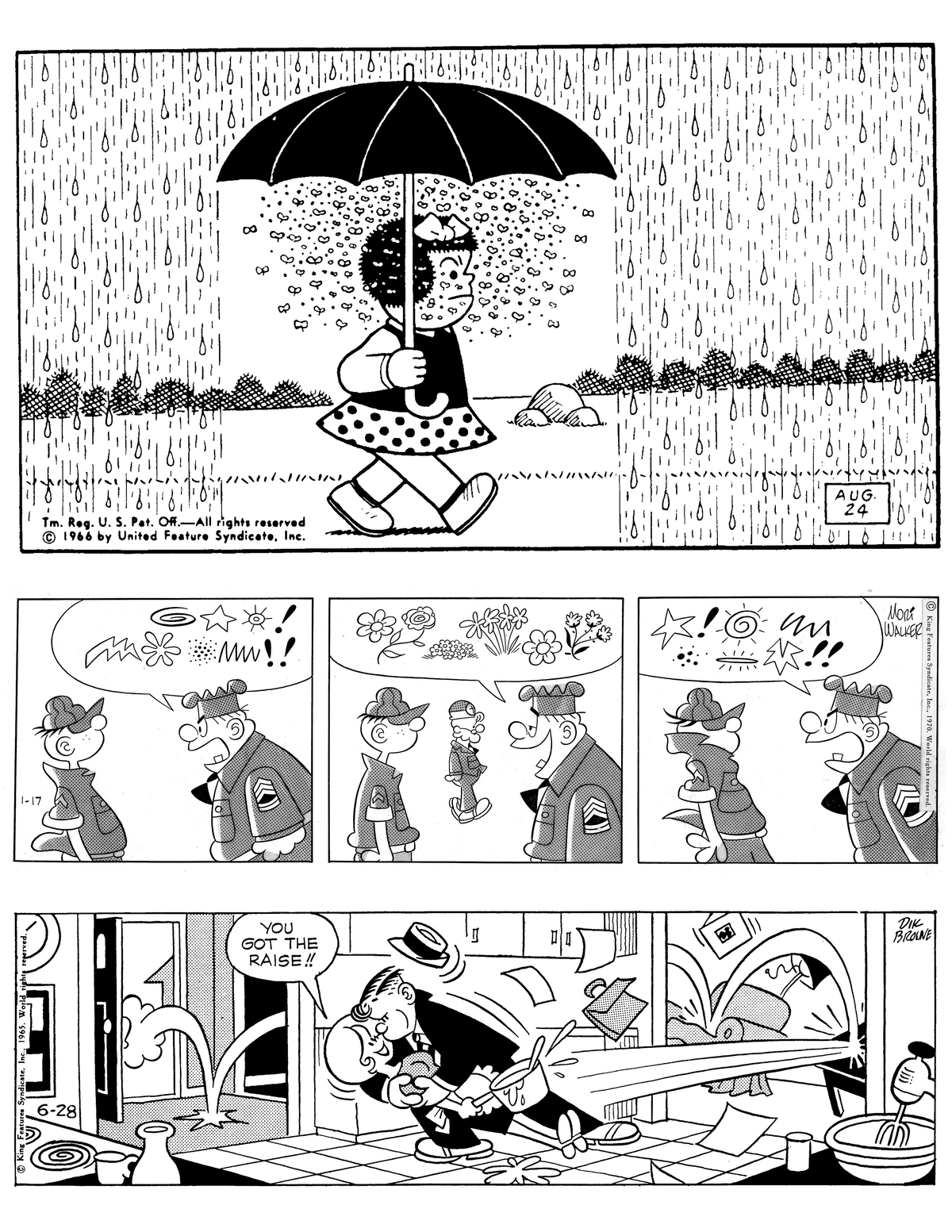

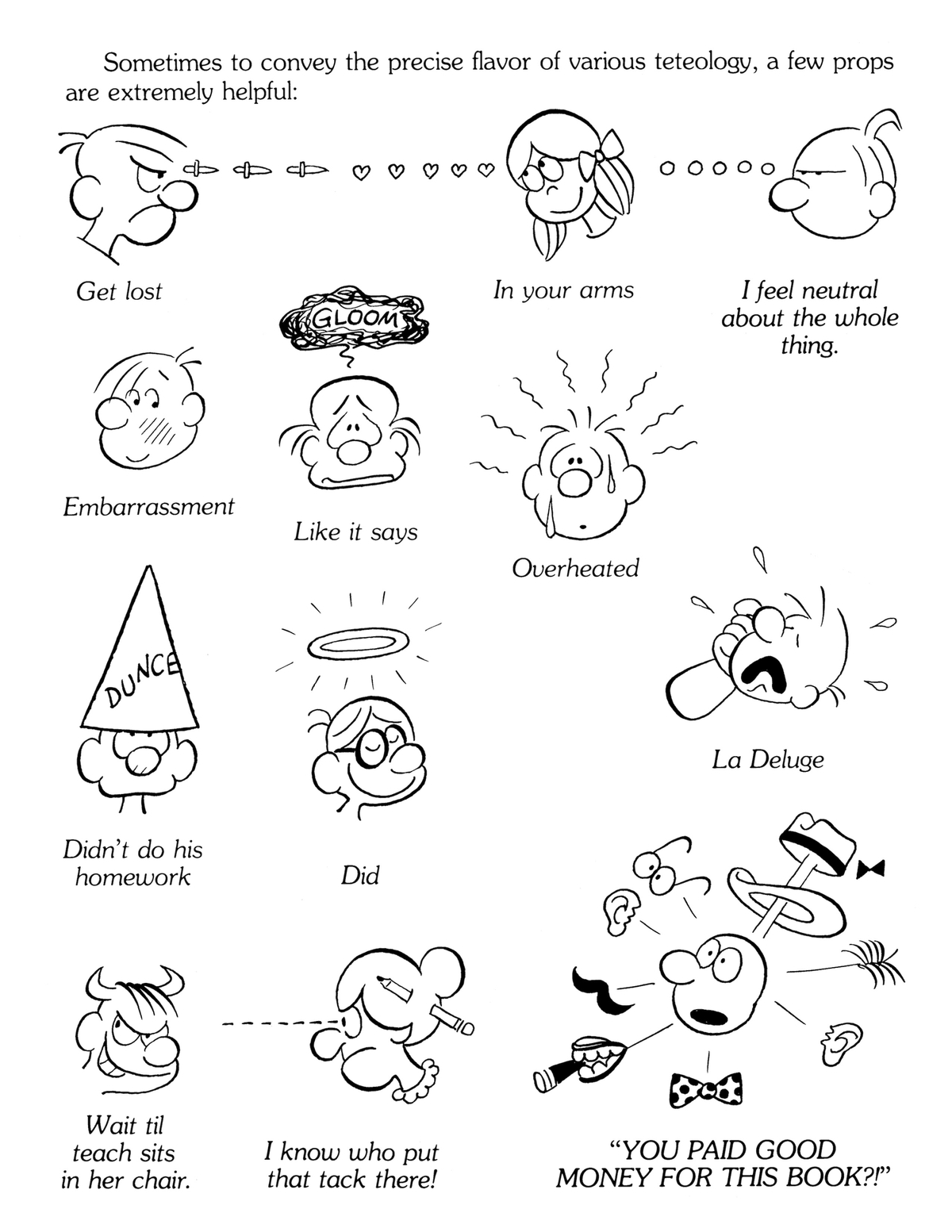

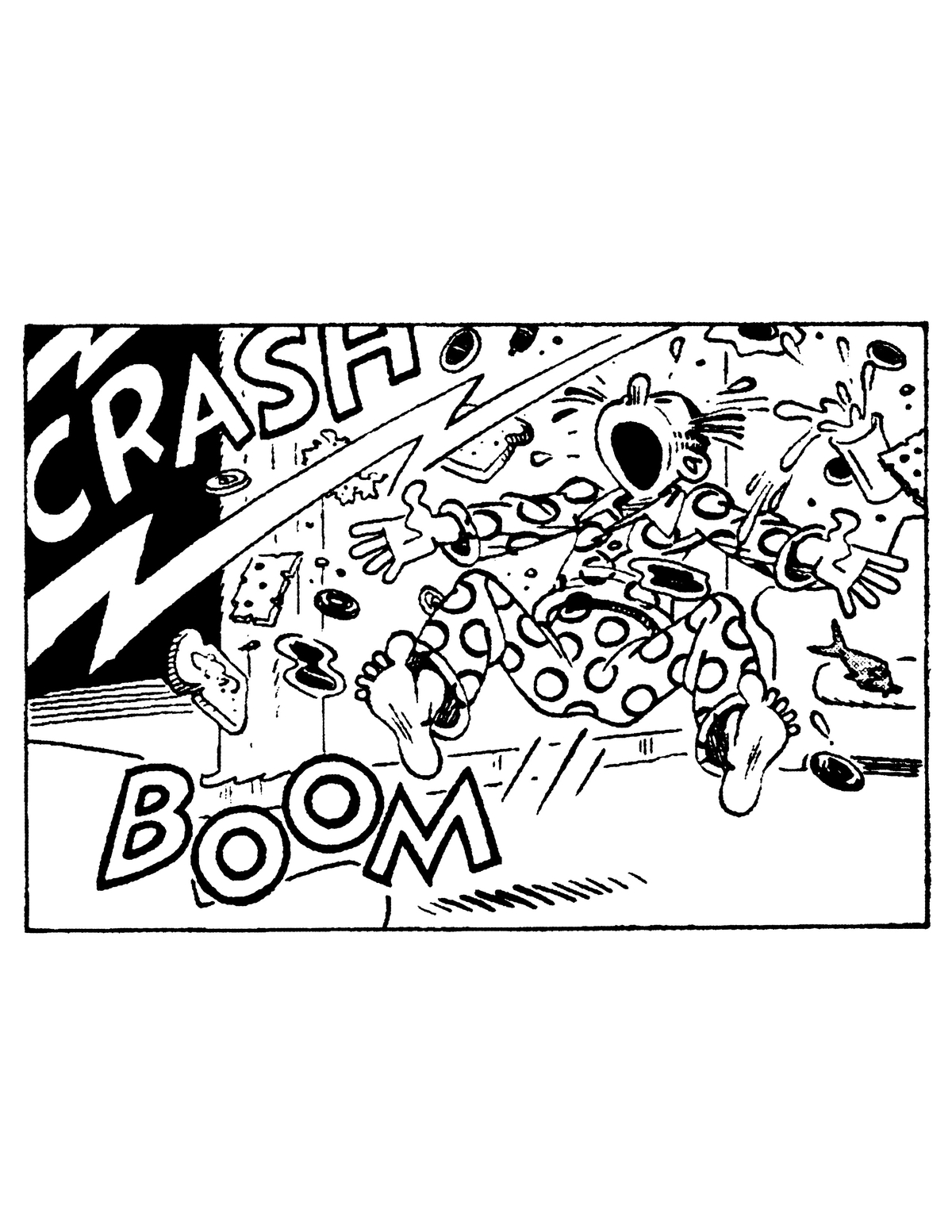

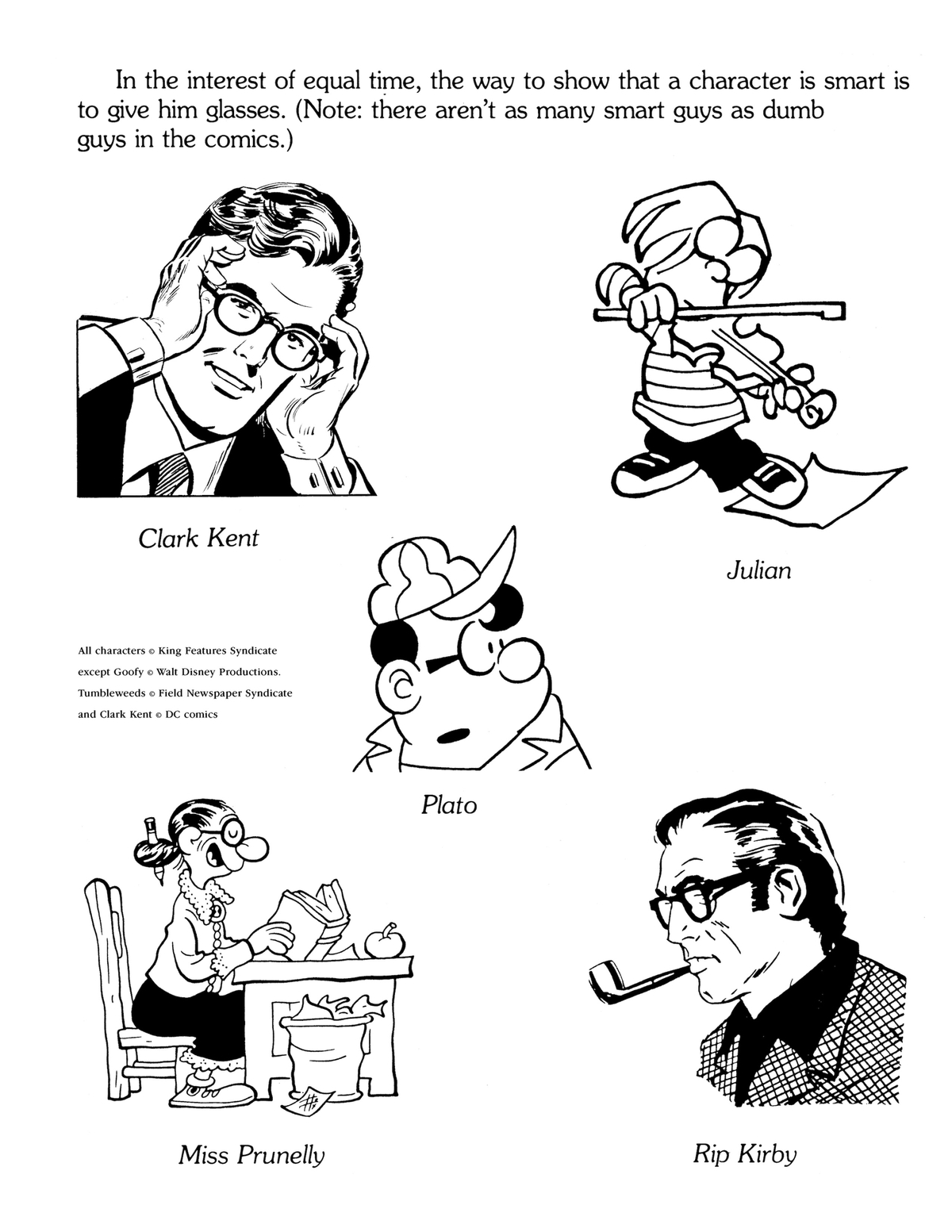

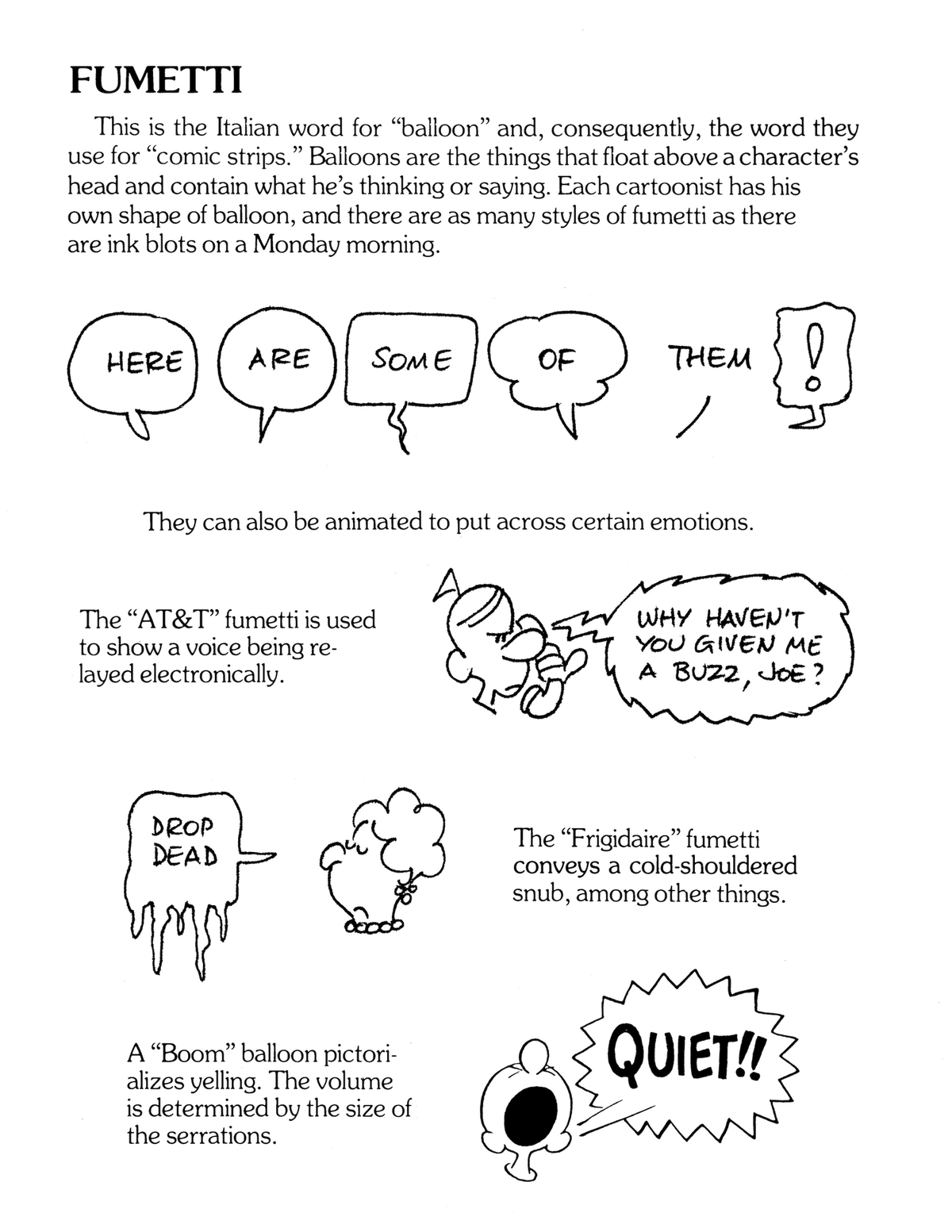

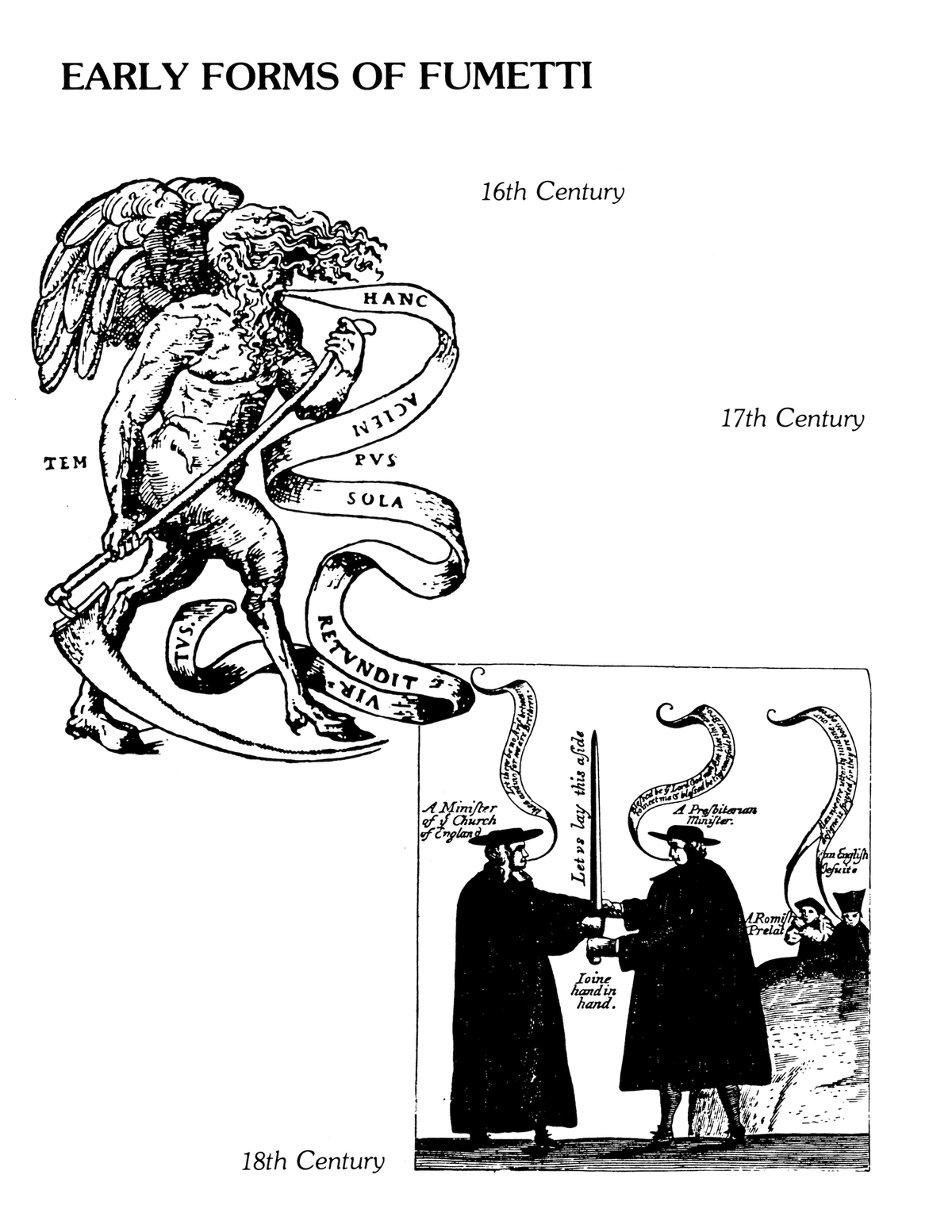

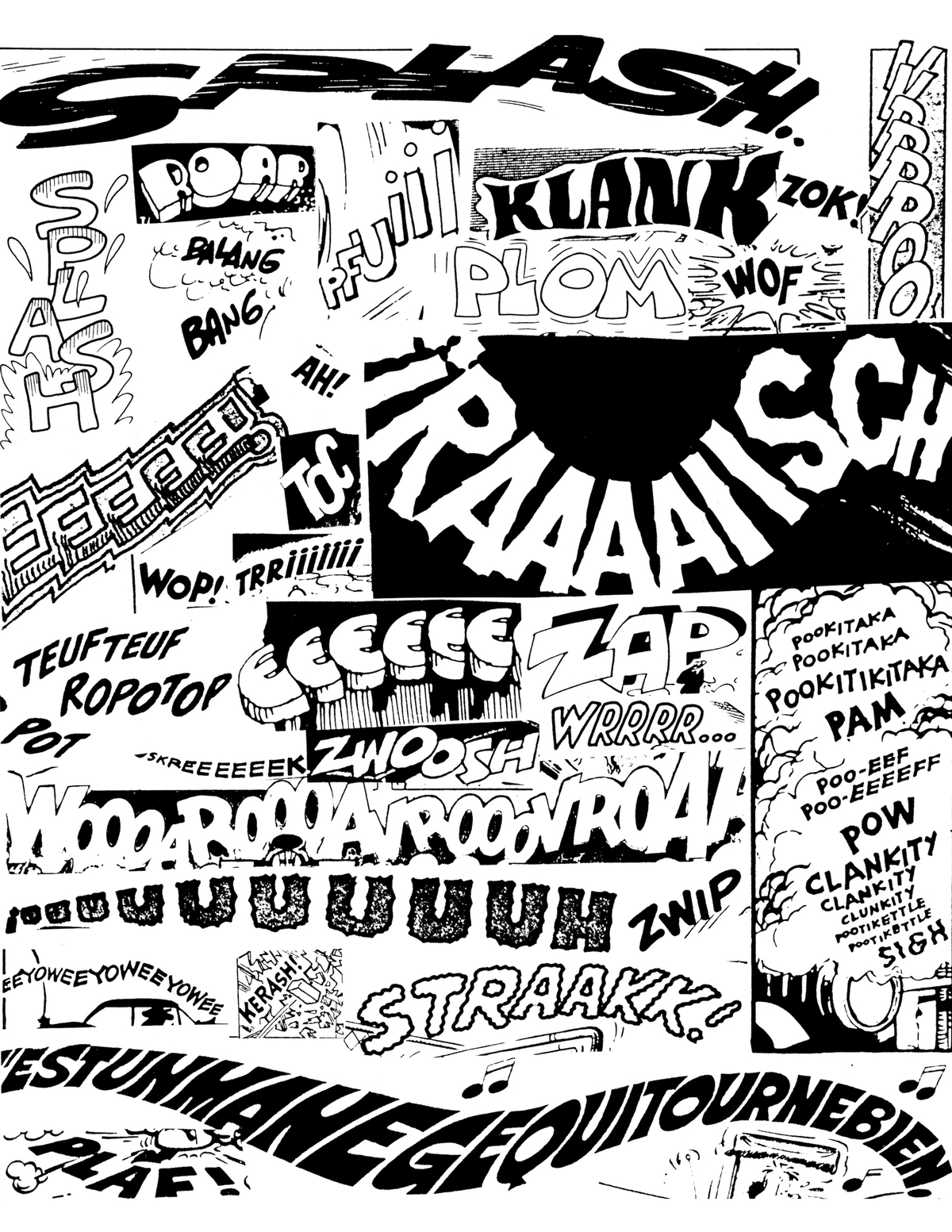

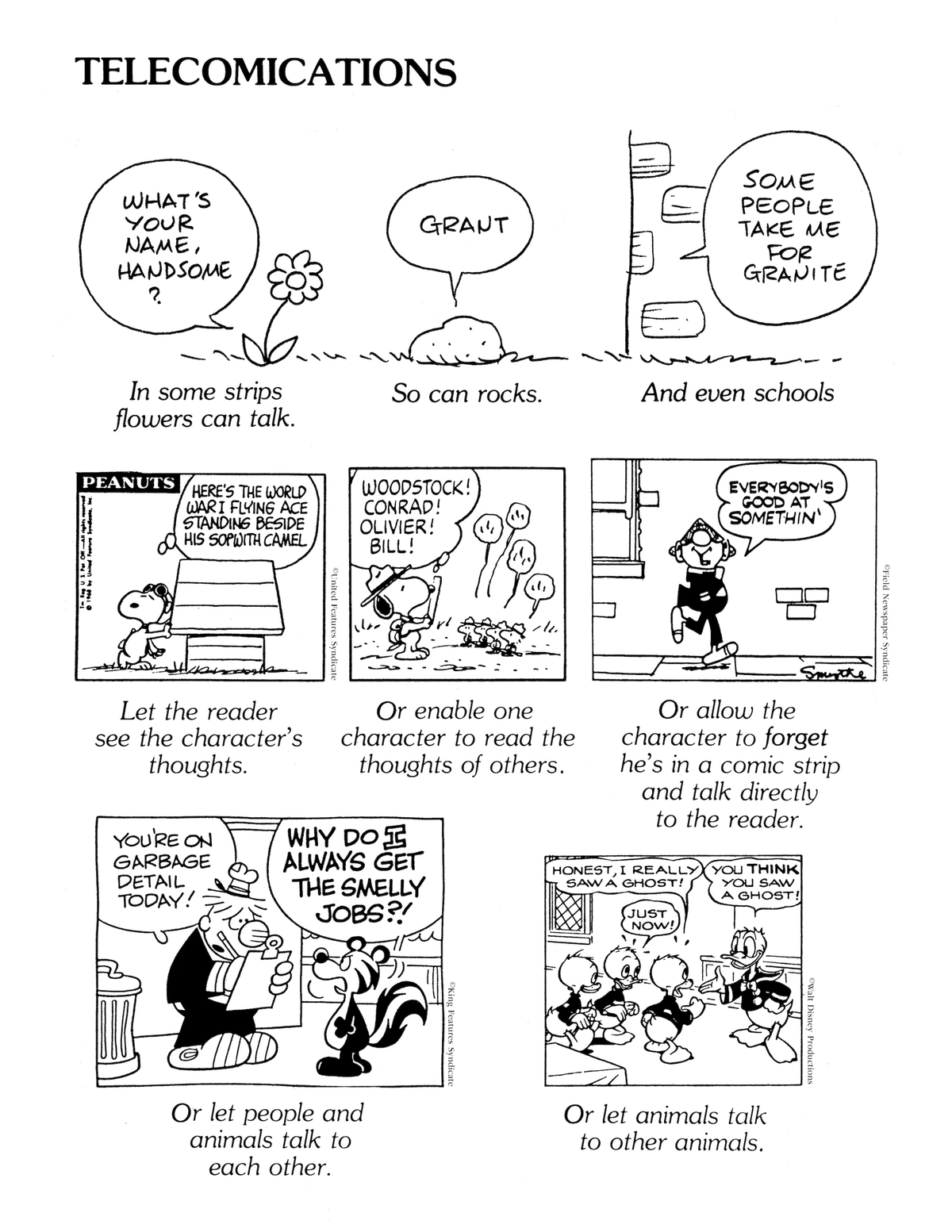

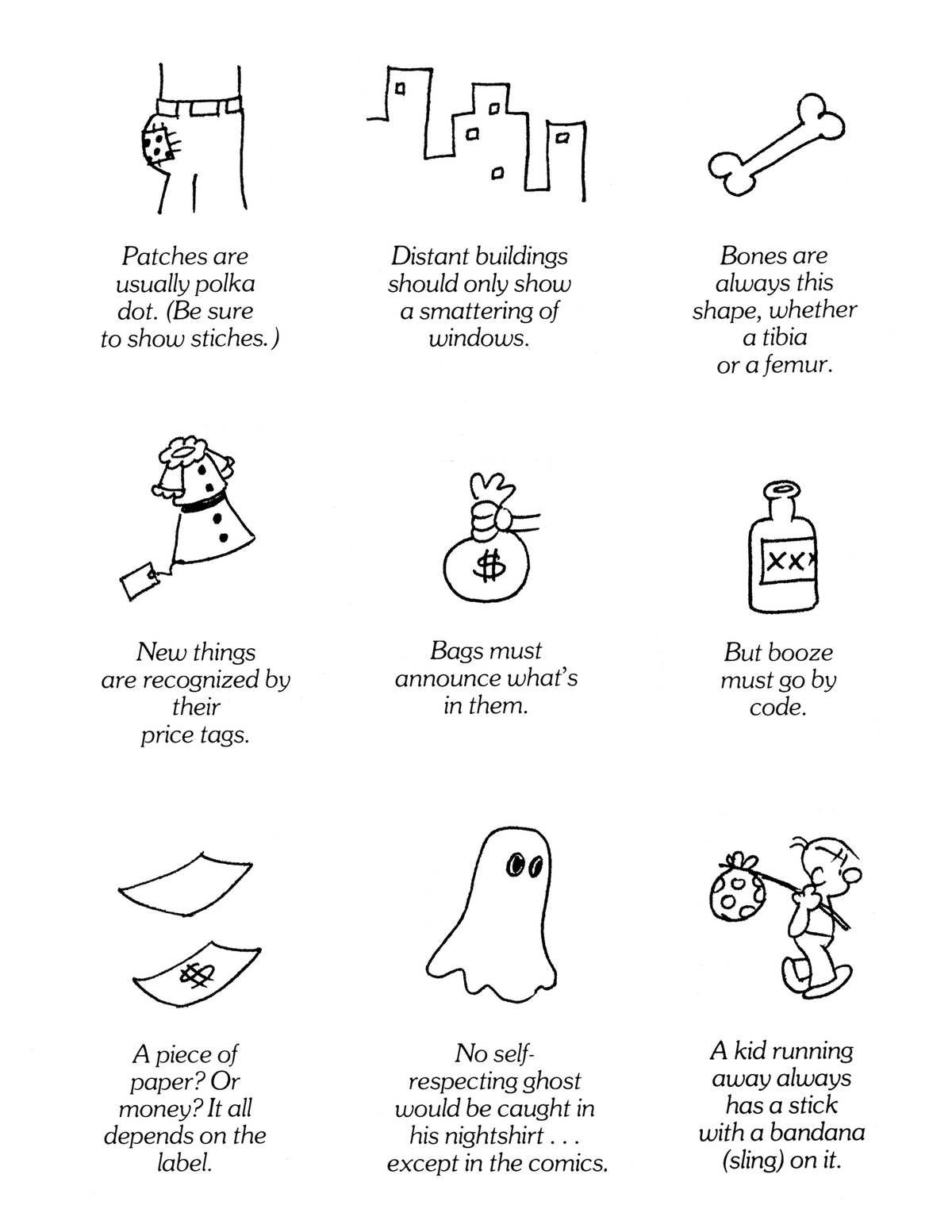

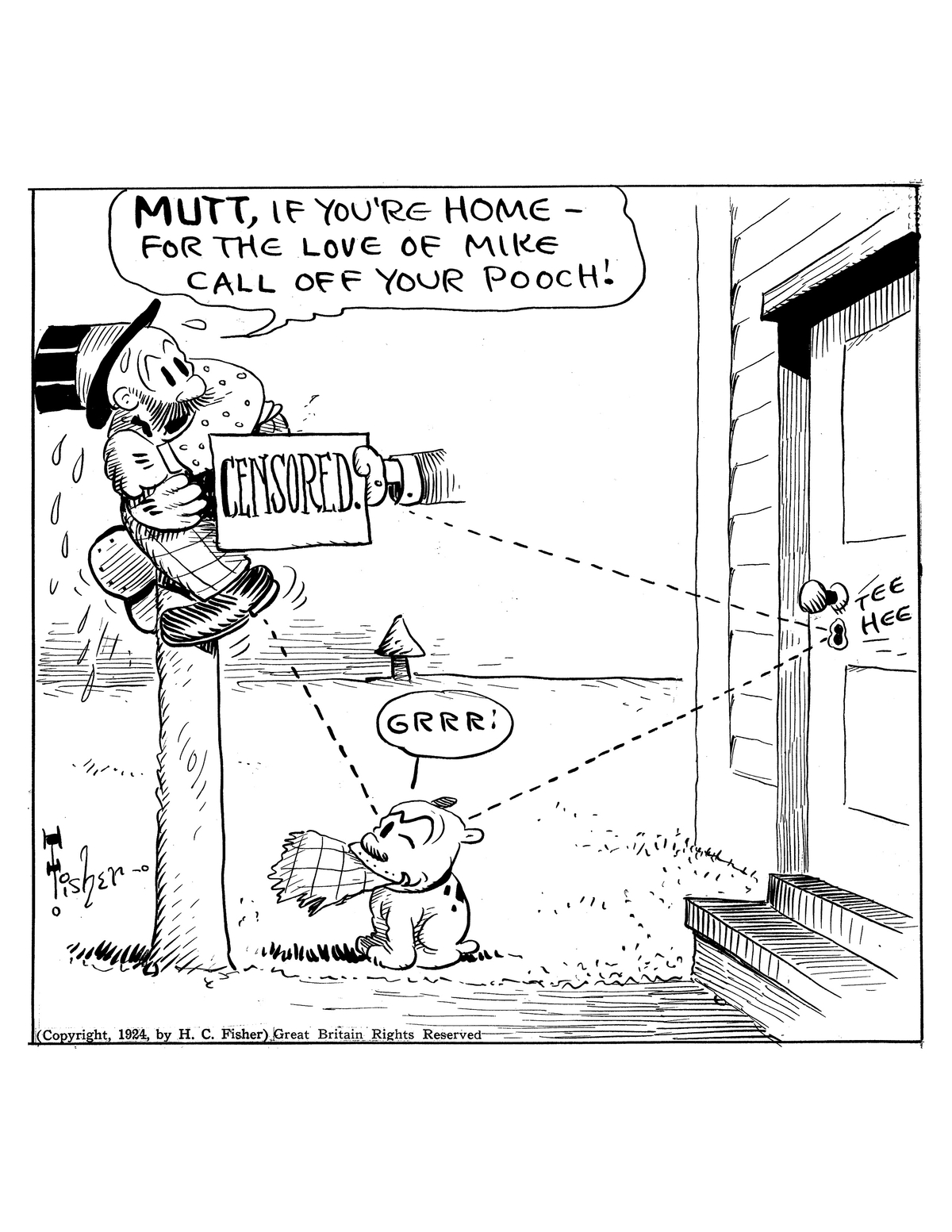

The cartoonist Mort Walker’s The Lexicon of Comicana—which began as an exhibition half a century ago at the Museum of Cartoon Art—offers a textbook case of life imitating art. Walker conceived his lexicon as a lovingly ironic send-up of comic-strip conventions. He invented names for time-honored graphic elements—for instance, hites and briffits, the straight lines ending in little clouds that convey the idea of speed—and gave new life to terms invented by others that had been circulating for a while (such as plewds, the small drops of flying sweat that indicate exercise or embarrassment).