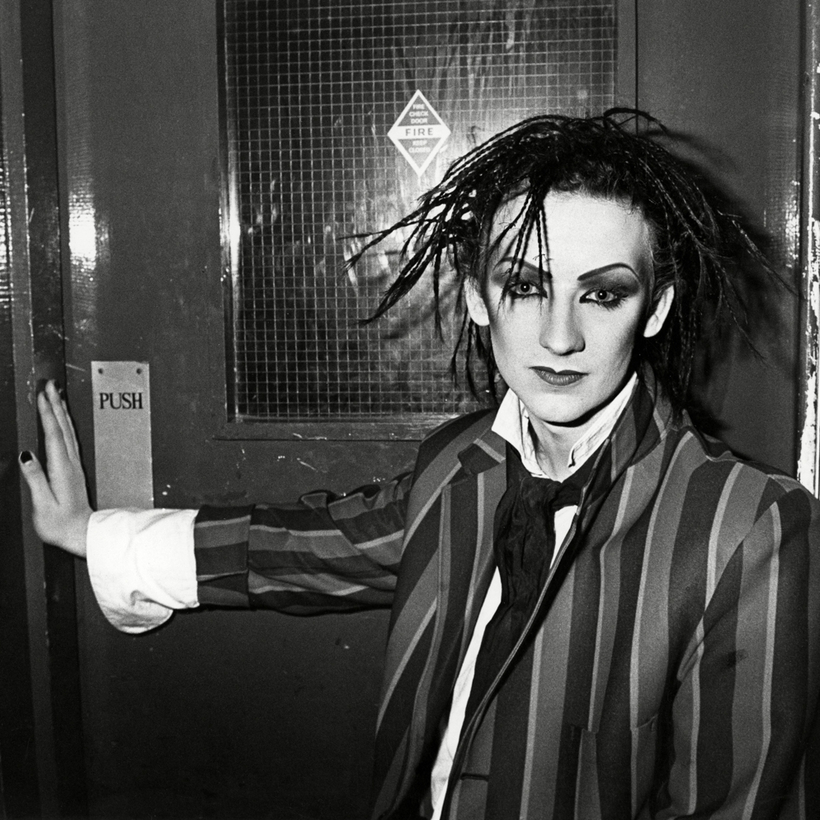

“The Blitz was an absolutely beautiful way to grow up,” Martin Kemp of Spandau Ballet recalls. “We didn’t talk about diversity back then because it was just part of the culture. The whole idea of new romantic was that you could be who you wanted to be: one day a soldier, the next a cowboy — or an Elizabethan cowboy — and it all made sense.”

In February 1979, on a dreary Tuesday night in Covent Garden — post punk, and amid the death rattle of disco — a new kind of club was born that fast became an incubator for a group of budding creatives. The club was the Blitz and it was to be the setting for a cultural earthquake that defined how the 1980s looked, sounded and felt. For 18 raucous months Tuesdays belonged to the flamboyant few. From 10 p.m. the pedestrian wine bar patrons were ushered out as Rusty Egan, the former Rich Kids drummer, began blasting out Teutonic electronica.