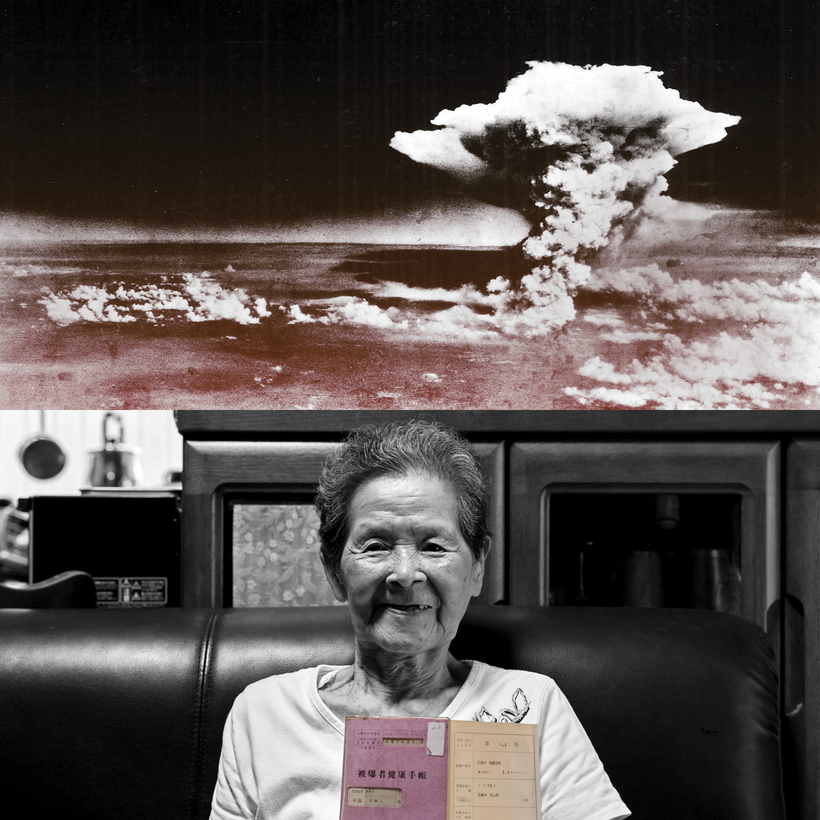

She was just eight years old, but a lifetime later Ayano Hirashima clearly remembers the first time she was exposed to an atomic bomb. It was Monday August 6, 1945, and she was taking off her shoes when the 13-kiloton uranium weapon nicknamed “Little Boy” exploded 635 yards above the center of Hiroshima, 30 seconds after 8.15am.

“I was about to pick up the indoor slippers to go into school when I saw the flash around me,” she says. “Boom! Suddenly I was covered in rubble. I managed to crawl out, and I got home somehow. My feet were bare and they were bleeding. I saw people in the fields — they might have been dead, although I was a child so I didn’t know.”