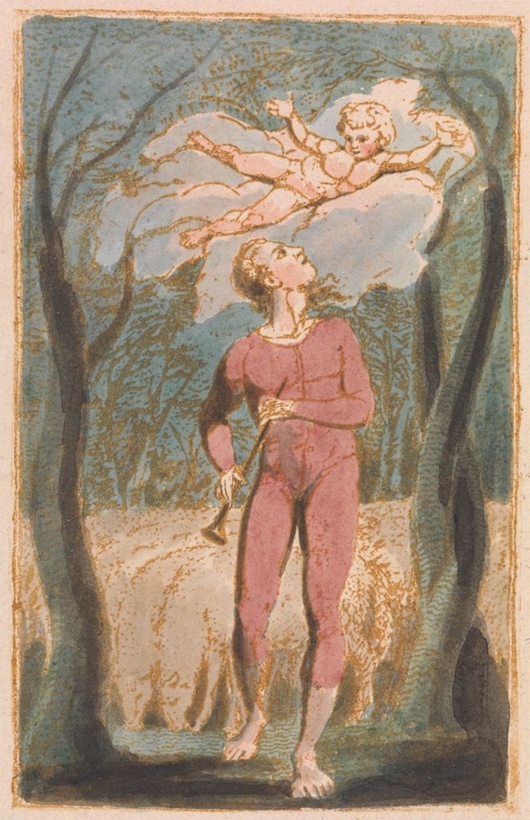

“I must create a system, or be enslaved by another man’s,” wrote the poet William Blake (1757–1827) in his book Jerusalem. And he did create a system. In manuscripts of poetry and personal mythology, using a printmaking process he invented, Blake’s words and illustrations intertwine in cosmic coherence. Inspired by visions he’d begun having as a child, Blake held forth on politics, literature, and history, often in immortal verse and with drawings pulled from his private fantasies.

“William Blake: Burning Bright” has just opened at the Yale Center for British Art, in New Haven, Connecticut. Organized by Elizabeth Wyckoff, the museum’s curator of prints and drawings, and Timothy Young, its curator of rare books and manuscripts, the exhibition presents Blake’s genius in its original form. It’s a “multi-sensory experience,” Wyckoff says of the more than 100 artworks on view.