It started out innocently enough. In the summer of 1892, Earth was making its closest approach to Mars in 15 years, causing excitement not only among astronomy buffs but the general public. To the naked eye, the fourth planet from the sun shone brighter than all the stars in the night sky. Through telescopes, ever improving technologically, Mars’s surface revealed itself to have exotic stretches of desolate, red-ocher terrain and more familiar-looking polar ice caps. Joseph Pulitzer, having recently purchased and turbo-yellow-ized the New York World, hyped these developments in his paper with such headlines as VISIT MARS! and MARS AND ITS MEN.

In his entertaining new book, The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America, David Baron, a former NPR science correspondent, brings to life the “Mars boom” that resulted from this confluence of factors. It’s a lively story that will be entirely new to most modern readers, though, like many a chapter in this country’s history, it’s a typically American tale of industriousness and can-do spirit that ultimately runs aground on flimflam, bunkum, bosh, and hooey.

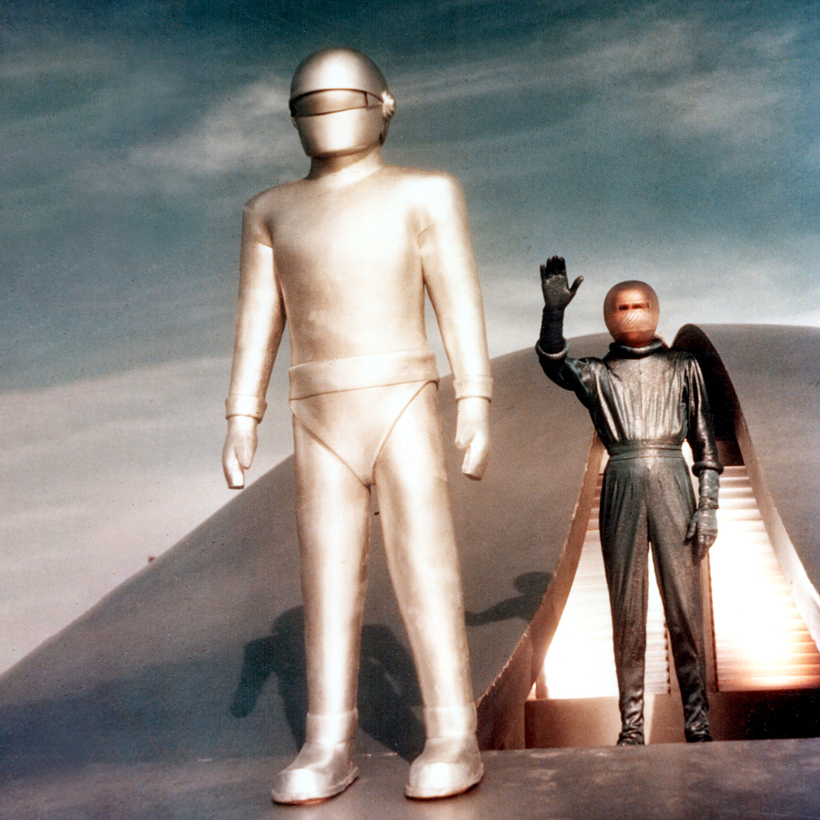

The “alien craze” suggested in the book’s subtitle is a little misleading. Unlike the Mars-mania that arose half a century later, when such gonzo 1950s science-fiction movies as Invaders from Mars and It! The Terror from Beyond Space served up slimy green men and Red Scare allegories, the period covered by Baron abounds with optimism and wonder. While Mars itself is the subject of fascination and rabid speculation, Martians, as a species and concept, remain mostly an abstraction. (Indeed, as The Martians begins, the very word “Martian” has not yet taken hold as le mot juste. Late-19th-century publications refer to the planet’s theoretical inhabitants variously as “Marsonians,” “Marsites,” and “Martials.”)

Baron’s protagonist is Percival Lowell, Harvard class of 1876, a pampered product of the Boston Brahmin family whose exalted place in the New England–society pecking order was summed up in the aphorism “The Lowells speak only to the Cabots, and the Cabots speak only to God.” By the early 1890s, Lowell wasn’t speaking much to anyone. He was a rich kid who had failed to launch. Though he briefly found validation as a lecturer on East Asia, having been one of the first Americans to travel extensively in Japan and Korea, he was prone to crippling bouts of what was then called neurasthenia and would now be called clinical depression.

But the press coverage of Mars awakened something in him. Lowell threw himself into astronomy, using his wealth and position to strike up friendships with the trained astronomers and fellow Mars enthusiasts Giovanni Schiaparelli, of Italy, and Camille Flammarion, of France. In the days before photography was an available tool, astronomers toggled between the viewfinder and the sketch pad, transcribing their telescopic findings to the printed page.

It was Schiaparelli who first noted a series of line-like markings across Mars’s surface, which he called canali, the Italian word for “channels.” He was being merely descriptive, but Anglophones in Britain and the U.S. mistook his intent and assumed he was talking about actual canals—intelligently designed bodies of water. Out of this misperception grew an orgy of reckless extrapolation, with Lowell presiding in the Hef robe. These Martian canals, he concluded, were surely built by a civilization of sophisticated beings, maybe or maybe not extant, who irrigated the planet and fostered agriculture by using meltoff from the polar ice caps.

In 1894, Lowell set up his namesake observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, whose elevation, remoteness, and dry air proved favorable to night-sky viewing. The Lowell Observatory stands to this day and is an important part of astronomical history; it is, for example, where Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto, in 1930. But as Baron relates in meticulously researched detail, Lowell, untrained and often unstable, did not approach his Mars-gazing with scientific rigor.

By 1903, he was compulsively turning out hundreds of drawings of Mars’s canal system, assigning them earthly names—the Euphrates, the Ganges—and embellishing his narrative of intelligent Martians ever further. If nothing else, his lectures and books proved inspirational to such authors of fiction as H. G. Wells and Edgar Rice Burroughs, who in turn inspired Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke. Baron dryly notes that Lowell also inspired his share of kooks, such as a well-dressed gentleman who calmly walked into a Gramercy Park church one evening and proclaimed to the congregants in all seriousness, “Listen, ye mortals of Earth, I am a messenger from Mars, the first ever sent by our glorious ruler to the mean inhabitants of this lowly planet.”

Over time, as astronomy grew more sophisticated, Lowell’s credibility steadily eroded. As early as 1896, he suffered a public-relations blow when he proclaimed with excitement that he had discovered a network of lines on Venus. Even back then, it was well understood that the surface of Venus cannot be seen from Earth—it is perpetually obscured by a layer of clouds. What Lowell probably saw was a projection of his own retina’s blood vessels onto the eyepiece of his telescope.

Baron is a clear, rigorous storyteller who, perhaps because he has spent so much time immersed in 19th-century clippings, occasionally lapses into waxed-mustache prose. (“The maples in Boston had turned and the evening was brisk when a procession of carriages and motorcars filled Copley Square as if it were a grand opera night.”) But I am grateful that he has disinterred this peculiarly American story.

It’s not giving anything away to say that we now know there are no Martian canals. What Schiaparelli observed in good faith, and Lowell in blind faith, were optical illusions caused by dust storms and the chance alignment of surface features like craters. The intrigue in The Martians comes from its author’s patient demonstration of how half-truths and subjective observations can snowball into consensus.

Modern politics do not intrude upon The Martians, you’ll be thankful to know. But reading it, I couldn’t help but think of another scion of a prominent Boston family who struggled for years to find his métier, traded on his last name to get by, and finally won a measure of credibility before going off the rails, consumed by fictitious anti-science narratives he asserted as fact. Today he is the secretary of health and human services.

David Kamp is a Writer at Large at AIR MAIL and the author of several books, including Sunny Days: The Children’s Television Revolution That Changed America