There was a time—a half-century before Donald Trump ordered 14 bunker-busting bombs and 30 Tomahawk missiles dropped on Iran’s nuclear facilities (“It was my honor!”)—when an American president spent New Year’s in Tehran. Jimmy Carter landed in the Iranian capital at sunset on December 31, 1977, for a 17-hour stopover en route to India. He held a private meeting with Iran’s ruling monarch, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, known as the Shah, then joined him for a banquet at Niavaran Palace.

As dinner was served, Carter raised a glass to Pahlavi: “Iran … is an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world,” thanks to the Shah’s leadership and “the admiration and love which your people give to you.” As detailed in Scott Anderson’s absorbing new book, Carter’s aides hadn’t approved his fawning tribute. One of them, a 42-year-old National Security Council official named Gary Sick, recalled thinking, “I wonder if that’s going to come back to haunt us.”

It did. King of Kings tells the story of the popular revolt that, within a year of Carter’s visit, toppled the monarchy, forced Pahlavi into exile, and brought to power a theocratic regime led by the fundamentalist Shiite cleric Ayatollah Ruholla Mussaui Khomeini. This diplomatic fiasco would not only doom Carter’s presidency but plague the foreign policies of his successors at immense cost in American blood, treasure, and prestige. “The radically altered Middle East chessboard created by the revolution has led directly to some of America’s greatest missteps in the region over the past four decades,” Anderson writes, “and it has been a crucial contributing factor to most others.”

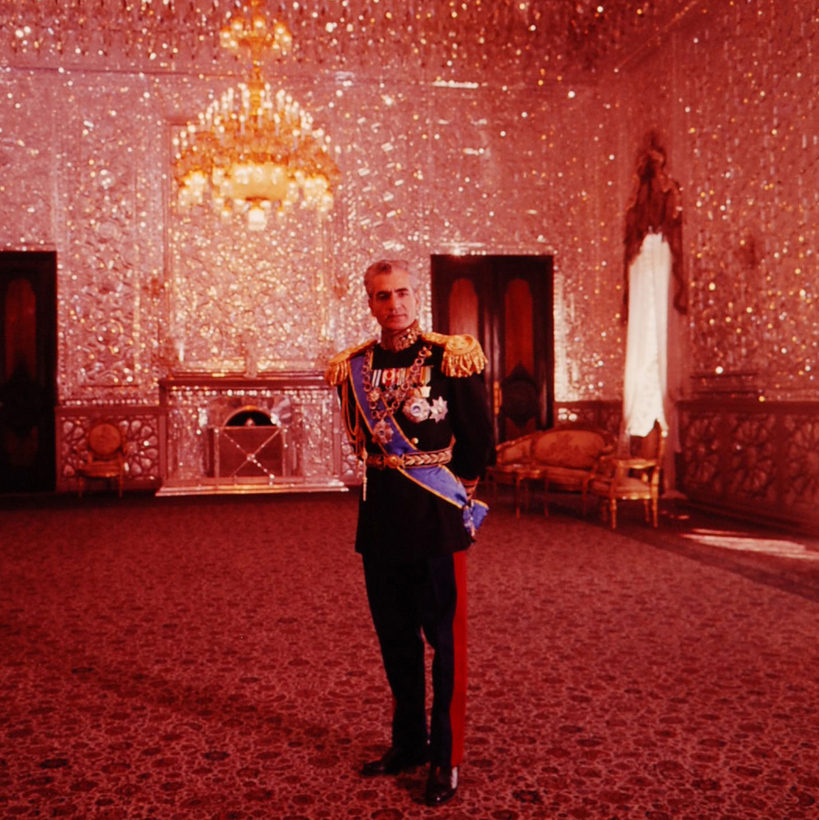

In Anderson’s telling, the bitter enmity that has come to define America’s relationship with Iran grew out of the coziness that preceded it. Installed by the Allied powers in 1941 at the age of 21, Pahlavi became Washington’s indispensable man in the Middle East, “a well-armed policeman working the beat in the most important and volatile neighborhood on the planet.” The C.I.A.-sponsored coup against nationalist prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh, in 1953, consolidated the Shah’s power, while also “forever marking the King of Kings as ‘the American Shah’ in the eyes of his countrymen.”

During the Cold War, U.S. reliance on Iranian oil produced a windfall for the Shah, which he used to finance extravagant building projects and parties, along with massive purchases of American weapons. By 1975, Iran’s military was the fifth-largest in the world and accounted for half of U.S. arms sales. At least 25,000 American workers and their families relocated to Iran, drawn by seemingly boundless commercial opportunities and “the lack of any motive to perceive obstacles ahead.”

That myopia was shared by the diplomats stationed in Tehran as well as successive U.S. presidential administrations, who dismissed Iranians’ resentment toward the Shah’s excesses and his foreign supporters. Despite a staff of 3,000, the U.S. Embassy in Tehran employed fewer than a half-dozen Farsi-speakers. King of Kings chronicles the ineptitude of the national-security establishment in anticipating the threat to the Shah’s rule posed by Khomeini’s movement. The C.I.A. never bothered to collect and translate the hundreds of cassette tapes of Khomeini’s sermons smuggled into Iran, which laid bare the cleric’s contempt for the Shah, Jews, and Western-style democracy. “Well into the mid-1970s, in the eyes of American officialdom,” writes Anderson, “Ayatollah Khomeini might as well not have existed at all.” Inevitably, the combination of American hubris and ignorance proved fatal, as the revolution gathered speed and spiraled out of the U.S.’s control.

While meticulously reported, Anderson’s ticktock of the Shah’s downfall lacks the élan of his previous book Lawrence in Arabia, about the end of the Ottoman Empire and the origins of Western attempts to remake the Middle East. Part of the problem was Pahlavi himself, “a waffler, an equivocator, even something of a coward” prone to blame-shifting and conspiracies. The moment the deposed Shah’s imperial plane lifted off from Tehran’s Mehrabad airport on January 16, 1979, “it seemed all of Iran erupted in jubilation.... Millions took to the streets to cheer and chant and embrace.” Anderson’s portrait makes it easy to understand why.

But that’s not the end of the story. Unbeknownst to all but a few members of his inner circle, the Shah was dying of leukemia. The book’s most riveting scenes focus on Carter’s struggle to resist pressure from the Shah’s powerful friends—notably Henry Kissinger and David Rockefeller, backed by National-Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski—to allow Pahlavi to settle in the U.S. Carter feared that doing so would wreck any hope of stabilizing relations with Iran’s new rulers, who’d already begun calling for “death to America.” Granting asylum to the Shah would only embolden the hard-liners and jeopardize the safety of the Americans still posted in Tehran. “Fuck the Shah!,” Carter erupts, after Brzezinski raises the issue once too often. “I don’t give a damn what happens to the Shah.”

Yet, in the end, the president relented, bowing to Brzezinski’s argument that abandoning such a stalwart ally would damage the U.S.’s credibility. “So what are you guys going to advise me to do if they overrun our embassy and take our people hostage?,” Carter asked, to silence from his advisers. On November 4, 1979, less than two weeks after the Shah arrived in New York for cancer treatment, a group of 125 Iranians stormed the U.S. embassy and took 52 Americans hostage, setting off a 444-day crisis “of such disastrous magnitude that both nations … are still dealing with its repercussions nearly half a century later.”

How long will they last? This summer’s 12-day war on Iran, waged by Israel and the U.S., has undoubtedly weakened Iran’s military capabilities; far less clear is the impact on the mullahs’ grip on power. “If the current Iranian Regime is unable to MAKE IRAN GREAT AGAIN, why wouldn’t there be a Regime Change???,” Trump posted on Truth Social. He might want to heed the warning of Khomeini’s first foreign minister, Ebrahim Yazdi, after being told of Carter’s decision to let in the Shah: “You are opening Pandora’s box.”

Romesh Ratnesar is a senior vice president at the Atlantic Council. He is a former State Department official and editor at Bloomberg Opinion and Time