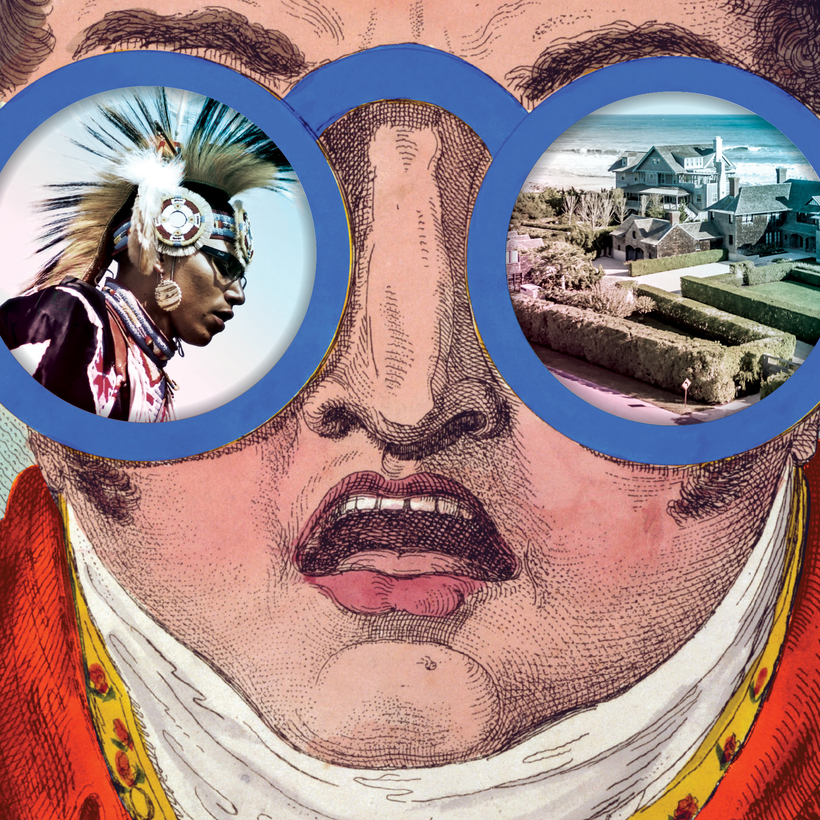

Every summer weekend, thousands of visitors and locals alike inch eastward on Route 27 toward the eastern tip of Long Island, encountering what locals call the “Shinnecock Squeeze”—a legendary traffic bottleneck that occurs when the two lanes narrow, becoming one.

To most, it’s an irritation en route to the East End. Few realize they’re passing through an Indigenous nation.