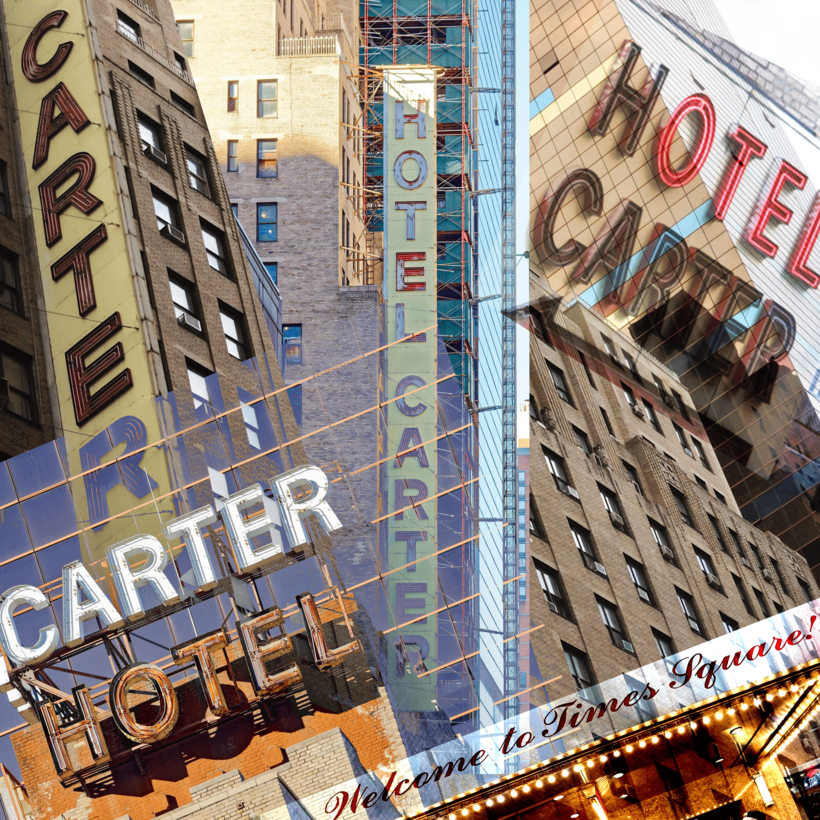

The bedbugs were bad. The breakfast was terrible. And the murders, many guests agreed, were far too frequent. There were the shootings in the strip club downstairs, a dismemberment on the sixth floor, and the occasional body falling from a window onto the street.

Not to mention the blood on the sheets. Blood on the curtains. Blood on the carpets. Multiple reports of “some kind of green and slimy mould” that hung from the ceilings and lubricated the door handles. Facilities dating “from the years of the Inquisition”. A one-eyed lady at the front desk who was “meaner than the fleas”.