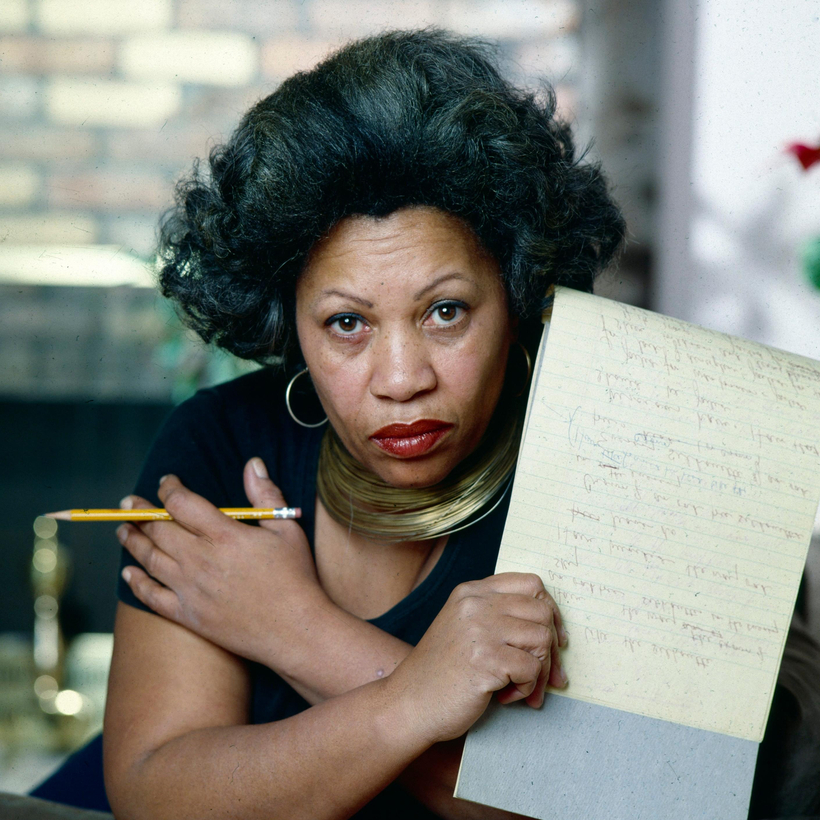

I’ve spent a lot of time reading Toni Morrison’s editorial correspondence from her time at the publishers L. W. Singer and Random House, where she edited more than 50 books between 1971 and 1983. During that time, some things I thought I knew changed.

I had heard, for instance, that Morrison was part of a group of Black women in New York (Alice Walker, Ntozake Shange, and June Jordan among them) who, in 1977, resolved to start their own publishing company. The most modest lore about Morrison’s involvement offered her as a key participant in the planning. The more elaborate versions had her plotting her escape from Random House and taking the Black women authors on her editorial list with her. As it turns out—the archive tells its own story—Morrison attended only one of the meetings of what Jordan dubbed “the Sisterhood,” and corresponded with members of the group only once or twice more about the kinds of things a start-up publishing house would need.