Ask ChatGPT to create a portrait of Quentin Blake in the style of Quentin Blake and the results are so preposterously bad, it’s tempting to think that artificial intelligence might not be the death of everything that is pure and good after all. Not yet, anyway.

I show its attempt to the real life Blake, who is sitting in a wicker chair in the bay window of his studio. Sunshine floods in. Parakeets screech from the elegant London garden square below.

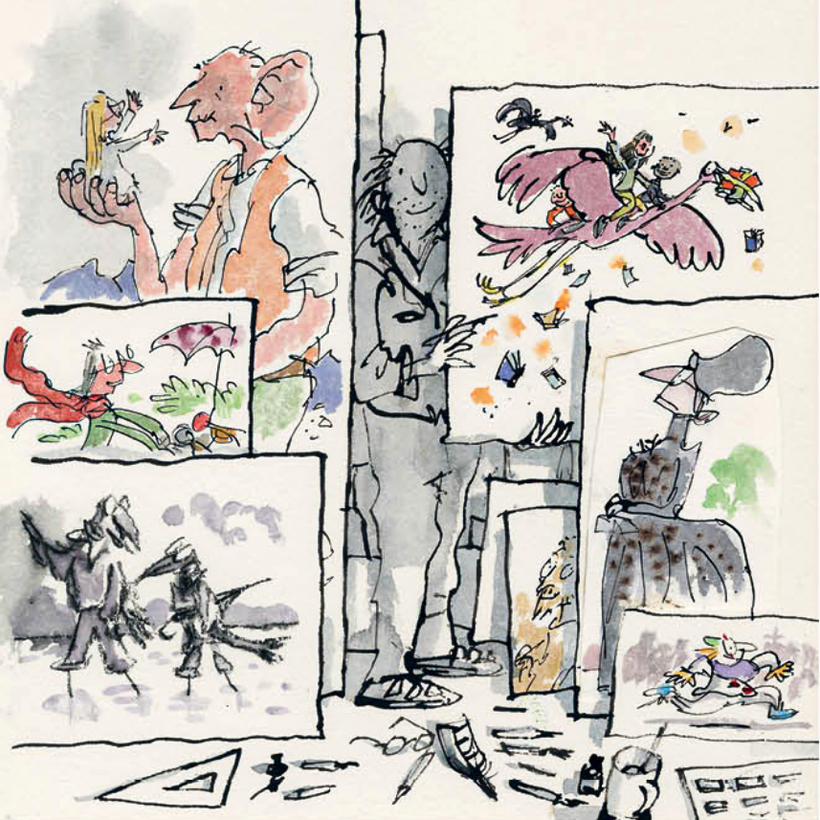

What does he think? “I can think of many things, none of them complimentary,” he replies with a twinkle. At 92, Blake is looking increasingly like one of his own drawings. Lively eyes. A wild wisp of hair. The lilac scarf gives the debonair flourish of a man who should be playing pétanque in the south of France, but the black ink stains all over one wrist suggest there is work to be getting on with. He is slower perhaps than he used to be, but still as spirited — his general demeanor that of a cheery tortoise. He has surprisingly soft hands.

Data mining, screen addiction, the plundering of copyrighted work, the number of children (and adults) who scroll instead of read: how alarmed is Blake by the many threats posed by Big Tech? “If I stopped to worry, I would worry. I think all I, or people in my position, can do is to go on being as interesting as possible.”

No software, nor for that matter any other artist can draw a line quite like Blake. As Chris Riddell, his fellow illustrator and former children’s laureate, puts it: “There are lots of people trying to draw like Quentin Blake. And there’s Quentin Blake. It’s very easy to tell the difference.”

The man himself rarely gives interviews these days, so the homogenizing force of digital culture only adds to the analogue thrill of sitting among the reed pens, quills and ink pots that clutter Blake’s studio in his flat in Earls Court, west London — the same studio where he has been working for 50 years.

There are two large desks, one for drawing, another for coloring. A jester’s hat sits on a shelf. On the mantelpiece, two squashed frogs — “real, I’m afraid” — are displayed in a picture frame for reasons no one can quite remember. A volume of Voltaire is kept close by his chair — Blake is fluent in French — and the shelves are packed with the classics he has illustrated over the years, including, I’m delighted to see, the same 1988 first edition of Roald Dahl’s Matilda that I received for my ninth birthday. It remains my most cherished hardback.

There have been homes in Hastings and in his beloved France, but this is now the permanent home he rarely leaves. Linda, his friend of 55 years, is there to support him, and a small, dedicated team, including an archivist and a conservator, keep the Blake empire ticking over. He cannot remember going a day without drawing. Linda tells me that if he stops halfway down the corridor and says, “I need to do a drawing,” he doesn’t mean in five minutes. He means right there and then.

These days, he wakes early. “Sometimes I’ll start drawing at 4am in bed, almost to cheer myself up. Hardly anybody ever sees these,” he says, reaching for a burgundy sketchbook he keeps by the bed and opening it to show a series of featureless heads in fuzzy red Biro.

Who do they depict? “I’ve no idea. I just make them up. This is what I’m drawing to entertain myself.” He likes the humility of a Biro — “the most pedestrian thing you can find to draw with. It’s what most people have in their pockets and I can’t help liking that.” Cars are his least favorite thing to draw. “Well, they have to be a bit battered — anything that’s very smooth is difficult. Whereas I’ve done drawings of people flying through the air on bicycles and things like that.”

Vision is an issue. “I have a problem with my eyesight at the moment. I find it very hard to read,” he says with some frustration. But don’t panic. Just as I am digesting what that means for the nation’s most celebrated illustrator, he triumphantly pulls out a huge magnifying glass. “I generally have one of these within reach so I can see what I’ve drawn. I can make sure that I’ve got the eye in the right place, that sort of thing,” he says with a chuckle.

It is in character that Blake should draw first, then check where things are. This, after all, is the man whose approach to life drawing at art school was to take one look at the model, then do the rest from his imagination. “I can almost say I never draw from life.”

Of course, I joke, you’re Quentin Blake, you can probably draw with your eyes closed. He nods. “I have done that.”

As if to prove the point, on the desk next to us is a drawing he completed two weeks earlier. It shows a man and his dog and it is beautifully, unmistakably Blake. The only concession to age is the scale: it is on a much bigger sheet of paper, the ink dipped from larger inkwells. Everything is scaled up, including his workload: Blake is busier now than in years. “I am hard-working but not out of a sense of duty or diligence. Because I like it.”

He is delighted that when he was appointed Companion of Honour in 2022, aged 89, he was told the award recognized not only past achievements but future ones too. “I thought it was extremely intelligent. I’ve had awards of one kind or another, but to give somebody a medal and say, ‘This is for what you’ve done, now go away and do some more,’ seems to me the most enlightening thing you could do.”

Which explains why this year there will be a big exhibition of his work at Lowry, Salford; another exhibition of 90 new drawings at the Bankside Gallery in London; new pro bono work to brighten the family rooms in UK prisons; and four new books.

Those who know Blake well say that, beneath the twinkle, there’s a certain shyness. Although his work fizzes with children and animals, he has never had children or even a pet. “I’d like a jackdaw or a parrot. But I couldn’t promise to look after it.” John Yeoman, his friend of 70 years and the writer with whom he collaborated more than any other, died last year. (He considers their 1984 project, The Hermit and the Bear, “the funniest book I’ve ever read”.)

I wonder if being one degree removed from the bright, busy worlds he draws helps him to capture something universal. Consider Zagazoo, for example. For my money his story about a bewildered couple who watch their baby transform into a series of different animals as he grows up is not just one of the best picture books, but the perfect parable of parenthood.

“Oh, I’m so pleased that’s one of your favorites. I enjoyed it tremendously,” he says, beaming. “I think the fact that I had not been through those experiences helped me. They’re the stages of childhood development. I just thought if I’d had children I might have been too close to it to think, oh, [now] he’s turned into an elephant.”

Has his drawing life required any personal sacrifices? “[It’s] the opposite of sacrifice. I’ve been well paid for doing what I like — and that also means I can do a lot of stuff that I don’t get paid for.”

Those pro bono commissions have resulted in some of his most interesting, least familiar work, such as his sublime drawings for a maternity hospital in Angers, France, of naked mothers meeting their babies for the first time. He had never personally witnessed that moment, so was delighted when a midwife later said to him: ‘“How did you know? We see that look all the time.’ That was marvelous. It was the best thing anyone could have said.”

Is he self-critical? “Well, if I am, I’m terribly nice about it,” he quips. “But actually, the correct answer is yes. That’s why very often I’ve done things twice. Some only see the light of the wastepaper basket. If I really don’t like them, I tear them up because it makes you feel better.” He describes himself as “a ridiculous optimist”.

If there has been criticism of his work, it is the cheerfulness, he says, recalling a scathing review for a show at the Dulwich Picture Gallery. The critic “couldn’t bear the cheerfulness. In the middle of the article, he said, ‘I hate it, I hate it.’ He didn’t like the smiles. That’s because I think he hadn’t seen enough. He hadn’t looked at enough pictures.”

Perhaps he hadn’t seen that image from Roald Dahl’s autobiography, Boy, showing the young Dahl being forced to warm the lavatory seat, which seems to lament the loneliness of every abandoned and bullied child at boarding school.

Or his heartbreaking illustration of Michael Rosen for his Sad Book, “being sad but pretending I’m happy”, as he reels from the death of his 18-year-old son, Eddie, from meningitis. “Try drawing that,” Blake says. “I did it 14 times.”

His work never seems to date. Why does he think that is? “It’s one of the things illustrations can do. It’s colloquial, easy to read, easy to understand. You don’t feel you have to have qualifications to do it. In a sense it’s spontaneous, but it’s very accurate actually.”

Does it bother him that he’s better known as a collaborator, rather than an author-illustrator in his own right? “No, I don’t think so. I wouldn’t want to be only illustrating myself.” He is bored with questions about Dahl, and prefers not to talk about him.

Next spring the Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration will open in London. It’s a project close to his heart. It will eventually house his archive, but he hopes it will also celebrate English illustration more broadly. He laments that his hero George Cruikshank, the caricaturist who illustrated the early works of Charles Dickens, is not better known, pointing to his engraving of Fagin in the Condemned Cell: “There isn’t anything in Oliver Twist as good as that picture. It’s extraordinary.”

How would Blake like to be remembered? He replies by saying how he would like his work to be remembered, as if the man and the work are one and the same. “I would like to think that it was spontaneous and cheerful, but also led you to take illustration seriously.”

Does he think about his legacy? “I’m not thinking about it,” he replies impishly. “But I am doing something about it.”

“Quentin Blake: Ninety Drawings” is on view at Bankside Gallery, in London, through July 27, 2025. “Quentin Blake and Me” is on view at the Lowry, in Salford, through January 4, 2026

Lucy Bannerman is a writer for The Times of London