André Bishop began his career in the theater as a bagman. He stood at the door of a tiny, impoverished Off Broadway theater holding a shopping bag and hoping people would throw in a few dollars at the end of the show to help keep the lights on. One man was especially generous. He came every night and always threw $20 into the bag. His daughter had a musical being performed at the theater.

Bishop eventually took charge of the organization—Playwrights Horizons—and turned it into a major Off Broadway institution. He produced plays and musicals by James Lapine, Bill Finn, Stephen Sondheim, Christopher Durang, and Wendy Wasserstein, who became one of his best friends. The man who gave Bishop $20 every night was Wasserstein’s father.

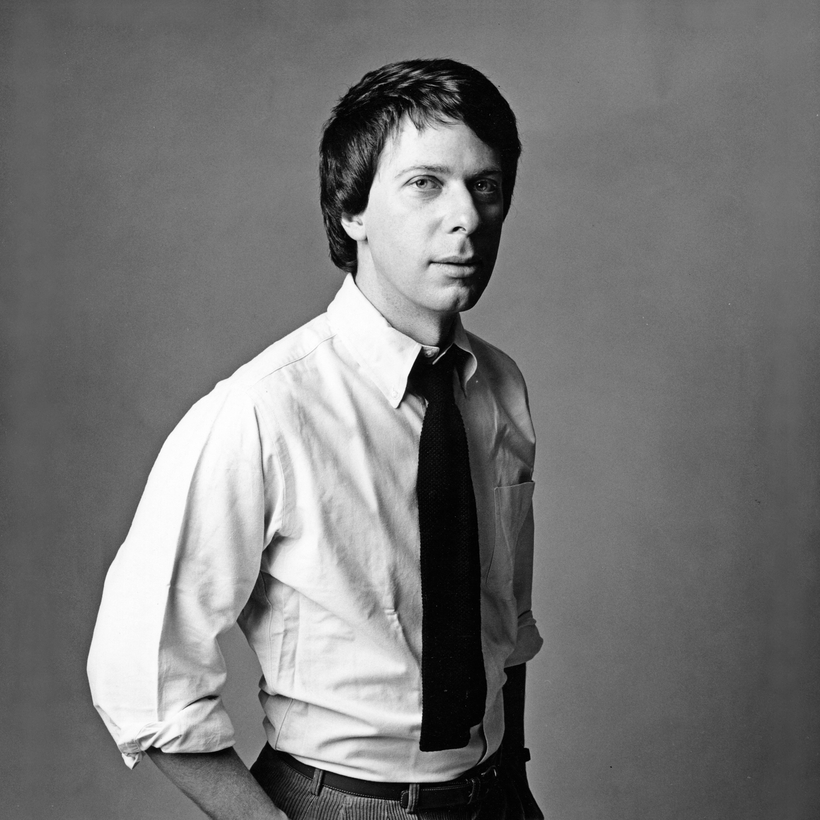

In 1991, Bishop landed one of the top jobs in the American theater—producing artistic director of Lincoln Center Theater. After 33 years, 11 Tony Awards, and 80 productions, he stepped down at the end of last month.

“It was time,” he says. “I wanted to leave the job with some sense that I wasn’t so decrepit and pathetic. I have this vision that in a year or so I’ll be selling pencils or apples on the street corner, and I want to have the energy to at least do that.”

Bishop was one of the most popular—and powerful—producers in the theater. But he exercised his power quietly. He wasn’t a flashy, tyrannical impresario such as Joe Papp, who created the Public Theater. Papp wore long camel-hair coats, smoked cigars, and shouted orders. Bishop, usually attired in a blue blazer, is elegant and soft-spoken. His biggest flaw, he says, is anxiety—but even that worked to his advantage.

“Wendy always used to say that the great thing about André as a producer is that you feel sorry for him because he’s more nervous than you are. Your nerves go away because you’re always trying to calm him down. She always thought that was one of my more endearing qualities.”

His father, a stockbroker, died when Bishop was five, and so he was raised by his formidable mother. “She was both loving and distant,” he says. “She was one of those people of her generation who didn’t fulfill what she might have wanted to.”

But she loved the arts and took him to his first Broadway show—Peter Pan, starring Mary Martin. He was enchanted. A black-and-white photo of Martin flying over the stage sat on a shelf above his desk. It was among the last mementos he packed up.

His mother sent him to boarding school, where he was “lonely and unhappy,” but “luckily I found my way to the theater.” After graduating from Harvard, Bishop came back to New York to be an actor. He wasn’t exactly a matinee idol. “I was inevitably cast as a doddering old person, 50 years older than I was, or the neurotic young man,” he says. “That was my contribution to the art of acting.”

Lost, with few jobs coming his way, he heard from a friend about Playwrights Horizons, a tiny theater run by Robert Moss devoted to new work. “What do you want to do here?,” Moss asked Bishop over lunch one day.

“I don’t know,” Bishop said.

“Well, come here and do something.”

Bishop answered phones, ran errands, and bagged money at the door. He also read submissions. Moss came to value his judgment. “I was the literary manager, though I didn’t even know what that was because I hadn’t been to drama school,” Bishop says.

Playwrights Horizons was located on West 42nd Street between 9th and 10th Avenues, a neighborhood that back in the 1970s was straight out of Taxi Driver. “There were ladies of the night,” Bishop recalls. “Some of them even claimed to have Equity cards and wanted to be in the shows. It was a slightly scary but extremely vibrant community, however odd it was.”

Moss was constantly scrounging for money. The dingy theater was badly in need of a facelift. He appealed to his friend, Richard Rodgers. The renowned composer didn’t send cash—he sent a truck full of paint, Lysol, mops, and brushes. “So that’s what we used to clean up the theater,” Bishop says.

With the help of Bob Ullman, a savvy publicist with strong connections to The New York Times, the theater got attention and attracted a following. The board expanded to include people who had a passion for the theater and, more importantly, money to keep it going. But after 10 years, Moss was worn out. “We have two choices,” he told Bishop. “One is to shake hands and close the theater. The other is that you take over.”

“What have I got to lose?,” Bishop thought.

What followed was an extraordinary 10-year run of attention-grabbing shows—Driving Miss Daisy, Sunday in the Park with George, Falsettoland, The Heidi Chronicles, Assassins.

Bishop thought he’d be at Playwrights Horizons forever. But then he was offered Lincoln Center. He accepted with some trepidation. He had run a theater with 299 seats. Now he’d have to fill the Vivian Beaumont, a 1,200-seat Broadway house. But his friend the director Gerald Gutierrez allayed his fears: “Oh, darling, just think about it like you’re moving into a slightly bigger apartment.”

Bishop had long harbored a desire to do full productions of his favorite musicals and plays with large casts. Playwrights Horizons was too small for that. The Beaumont was perfect. And Bishop filled it with sumptuous, critically acclaimed revivals of Carousel, South Pacific, The King and I, and My Fair Lady. He also produced Wasserstein’s The Sisters Rosensweig and several Tom Stoppard plays—Arcadia, Hapgood, and the nine-hour epic The Coast of Utopia, which won the Tony Award for Best Play in 2007.

With his enviable track record, I wondered why he never became a commercial producer. He was well compensated at Lincoln Center—nearly $1 million a year—but with his eye for hits he could have made 10 times that on Broadway.

The thought never occurred to him. “I love the life inside these buildings,” he says. “Putting on plays is great, but the daily life of a theater company is what I’m going to miss the most. The chance meetings you have with a staffer who needs advice. The artist who drops in just to say hello. The performance that doesn’t start for an hour because someone is sick, and you have to get up and make a speech. I’m an institutional person because I believe, at their best, institutions create and sustain artists.”

His next act won’t be selling pencils on the street corner. He’s headed to the American Academy in Rome to work on a long-anticipated memoir.

“I’m very happy to be going away from New York for a couple of months, away from a routine that I’m no longer going to have. A complete change is going to be good.”

Michael Riedel is the author of Razzle Dazzle: The Battle for Broadway and Singular Sensation: The Triumph of Broadway