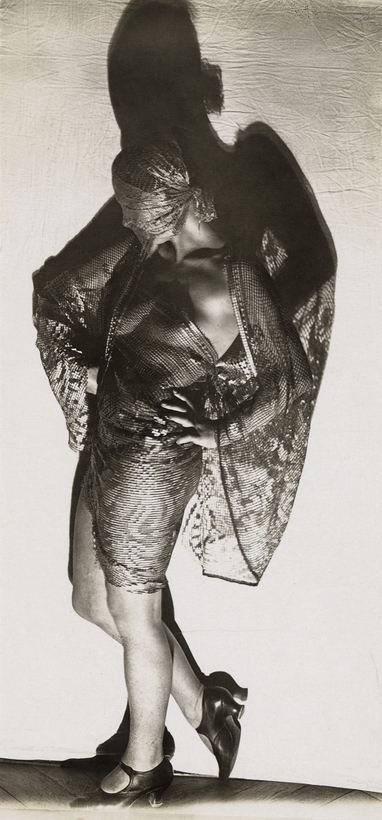

Career. Reputation. Legacy. In the art world, these can all hang by a thread. No one knew this better than Marta Astfalck-Vietz, a photographer and painter who operated during the heady days of late-1920s Weimar Berlin. Astfalck-Vietz was an experimental pioneer of the “combi-photo” and a taboo-breaking explorer of her own body, but her entire archive of negatives was destroyed in 1943, when an Allied bombing raid incinerated her studio. That we have anything to look at in the 21st century is due to the fact that she often sent folders of her work to her father, Reinhold, who kept the photographs safe. A collection of them is now on view at the Berlinische Galerie Museum of Modern Art, in an exhibition that opened yesterday, “Staging the Self: Marta Astfalck-Vietz.”

Like so many Weimar-era free spirits, Astfalck-Vietz saw her career abruptly hobbled by the political ascent of Adolf Hitler, which began in 1933. By the middle of the decade, she had virtually ceased working as a photographer, instead devoting her time to intricately detailed watercolors of plants, flowers, and shrubs. Nor was she helped by a self-confessed naïveté when it came to claiming credit for her work, and so Astfalck-Vietz’s name disappeared from the record.