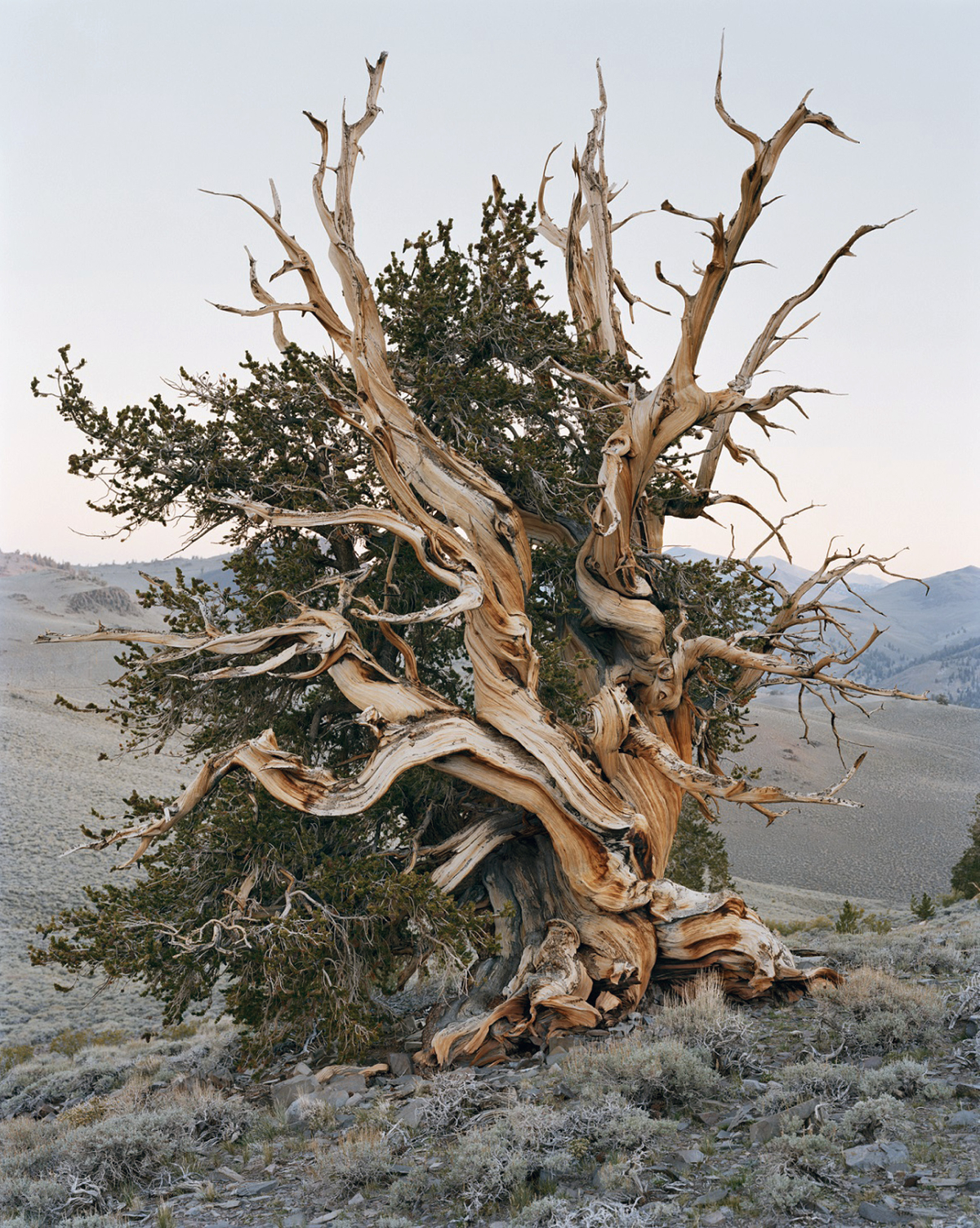

In 2020, Mitch Epstein discovered a pocket of old-growth forest near his childhood home in western Massachusetts. There were bristlecone pines, bald cypresses, and giant sequoias—trees that had swayed through sun and storm for hundreds, even thousands of years. Most had remained untouched by human hands.

One-third of the world’s forests are considered old-growth, Epstein learned, though few remain in the United States. He set out to photograph those that do—from California to Washington. Some trees stretch straight into the sky; others weave intricate webs of branches. The project took four years.

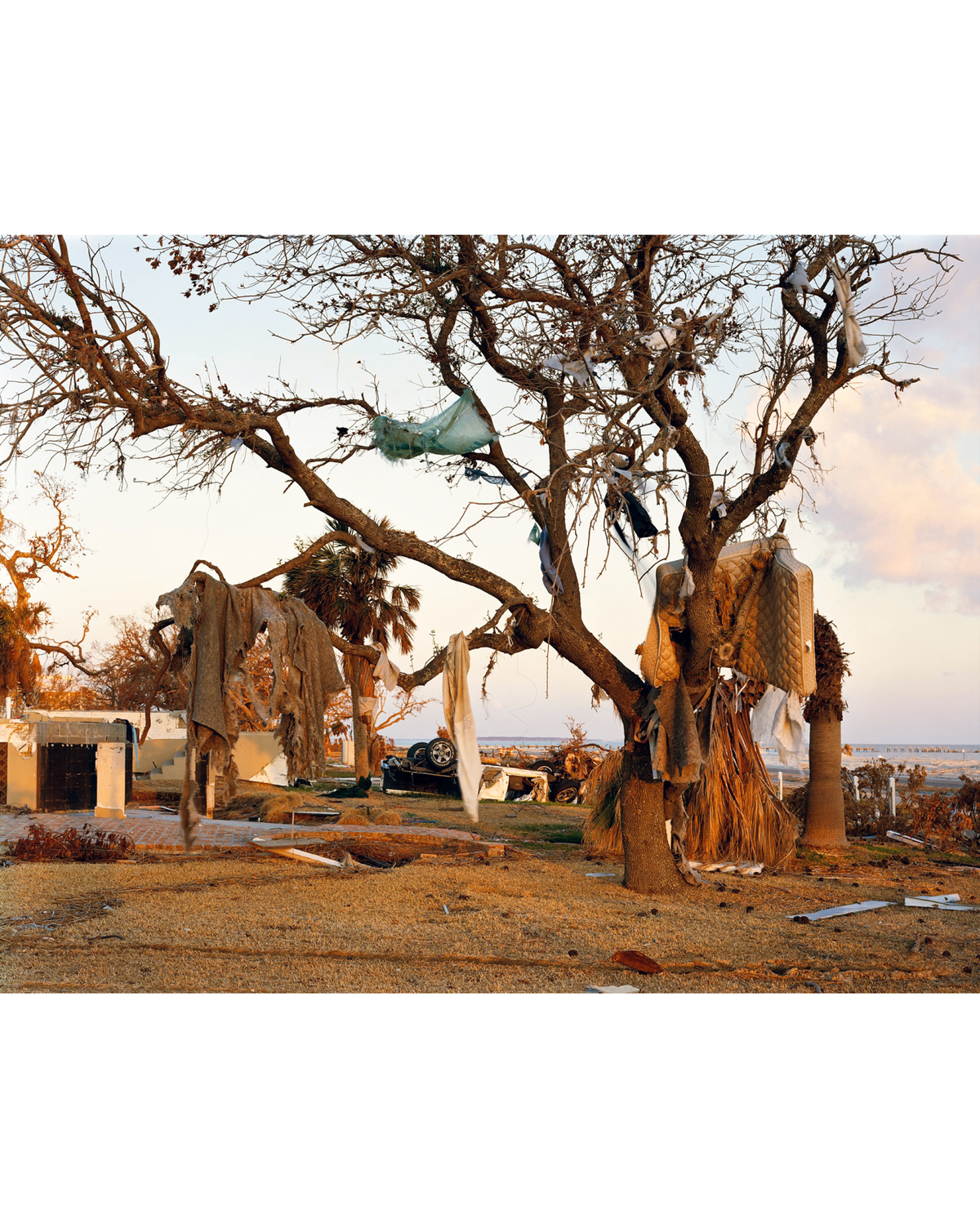

Epstein has long examined the collision of nature and industry, linking environmental degradation to human ambition and control.

In the early 2000s, The New York Times sent him to Cheshire, Ohio, a town overtaken by a power company. That assignment sparked a five-year journey across the country—from the BP Carson refinery, in California, to the Hoover Dam, to an oil platform off the coast of Alabama. In West Virginia, football players in red jerseys practice beneath the looming Amos coal plant, its smoke curling into the sky. In another image, prairie homes sit unsettlingly close to the grid that sustains them.

Questions of landownership—does it belong to those who live on it or to the corporations that buy it up?—are central to Epstein’s work. In 2017, he turned his lens to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North and South Dakota. This was Indian land, and thousands had gathered to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Published last March, Mitch Epstein: American Nature collects these quietly awe-inspiring photographs from a 20-year odyssey. Together, they form a portrait of a country shaped—and scarred—by its use and abuse of the land.

“I am not,” Epstein says, “an ecologist, nor a scientist, nor a politician, but I am capable of listening and observing.” —Elena Clavarino

Elena Clavarino is the Senior Editor at air mail