He grew up in the backstreets of São Paulo, where his friends knew him simply as José. That’s the story. But when the studious son of a mechanic stumbled across the great works of English and Scottish literature, everything changed.

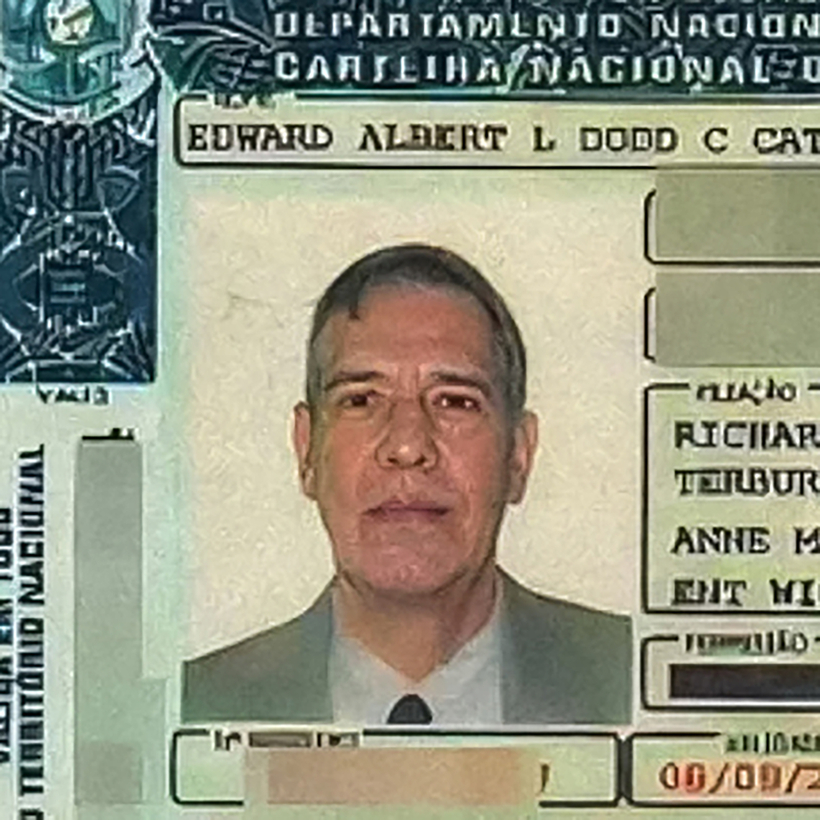

José Eduardo dos Reis became Edward Albert Lancelot Dodd Canterbury Caterham Wickfield, it is claimed. With a moniker inspired by his favorite author, Charles Dickens, he served as a judge on the Brazilian bench for 23 years while pretending to be the descendant of British aristocrats.