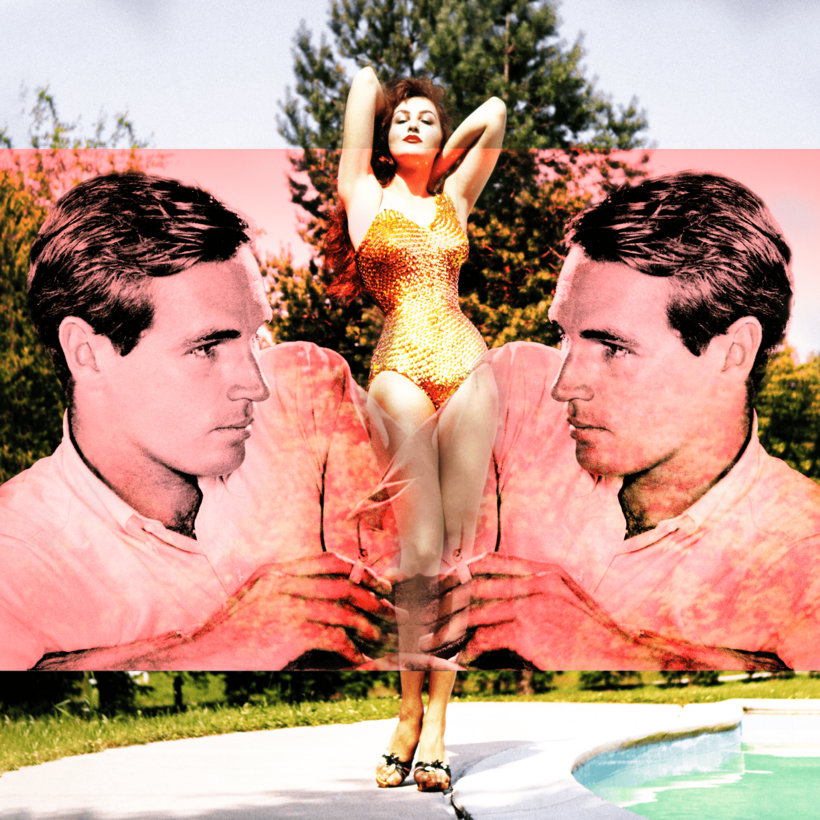

There he was, in a photograph on the floor, this drop-dead gorgeous man whose image struck me like lightning. It was the end of the 1950s, but I still remember the picture so clearly. In it, he was leaning forward on a shabby velvet couch, holding a cigarette. It didn’t look like he smoked. The photo was strewn among others of actors and performers, perhaps left after a casting session.

Who was this man? Where in the world did he come from?