They were largely anonymous and unsung, sons of immigrants, restless and creative minds, storytellers, dreamers. They invented an entire universe that, almost a century later, stands as a tentpole of American popular culture, though only recently has their work attracted the interest of museum curators. And Jack Kirby was perhaps the greatest of them all.

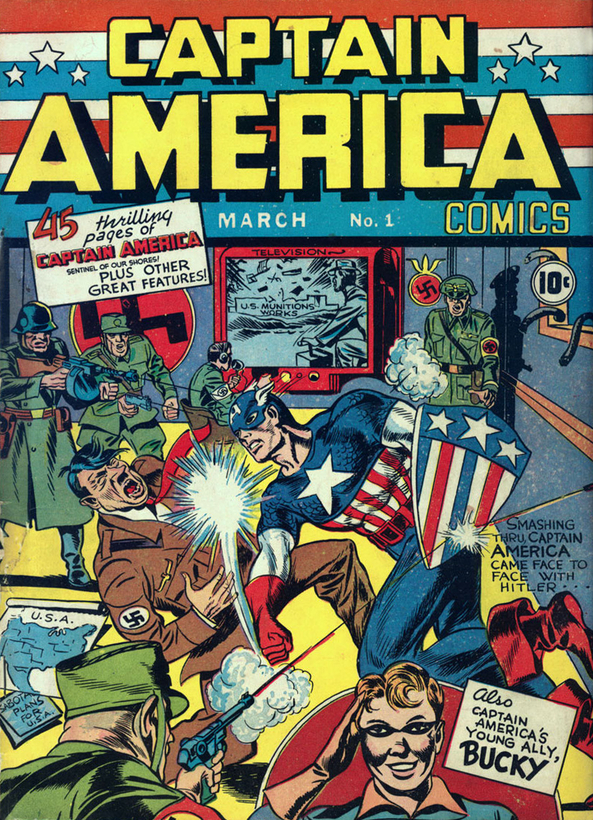

Over a six-decade career, Kirby created or co-created some of Marvel Comics’ most fabled heroes: the Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk, Captain America, Iron Man, the Avengers, the X-Men, and the groundbreaking Black Panther. But of equal significance was the inner complexity of his characters. Kirby transformed superheroes from two-dimensional cops with capes into layered, conflicted individuals. The first-ever retrospective of his trailblazing work, “Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity,” opened last week at Los Angeles’s Skirball Cultural Center.

Kirby began his career as a newspaper-comic-strip writer in the 1930s, graduating to comic books after returning from service in Europe during World War II. Over the next two decades, as Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman devolved into camp silliness (an era that reached its nadir with the Batman television series in 1966), Kirby zigged as the rest of his industry zagged.

He intuited that readers were yearning for heroes who were flawed, who struggled with their own emotions, shortcomings, and broken moral compasses as they trod the path of righteous justice, who were recognizably human, even if they were superhuman. What the fantasy world of superheroes needed, he thought, was a dose of realism.

Kirby first tested his theory with the Fantastic Four, a quartet he created in 1961. They were sarcastic, flashy, and convinced of their own superiority. At times petty and vain, they rejected “secret identities” in favor of fame, and squabbled like a sitcom family. Moving from Marvel to DC Comics in 1970, Kirby even remade “Superman’s pal,” geeky Jimmy Olsen, into a counter-culture hipster brimming with swaggering machismo.

At DC, Kirby continued writing plots with topical storylines that raised vexing moral questions. His vivid drawings, meanwhile, showcased angles, scale, and shading that the medium had never seen before, with bold color palettes that made pages pulse with energy. The new point of view upended the entire industry. Grit, interpersonal conflict, and moral ambiguity were in; comicality (remember Mr. Mxyztptlk?) was out.

Featuring archival comic books, canvases, interior panels, and sketches (including Kirby’s first concept drawing of Black Panther, who looks like a grinning Barack Obama dressed as a Roman gladiator), the exhibition breezily traces the artist’s life from beginning to end, starting with his early work illustrating titles such as Young Romance to the signature characters that forged his legacy. Ephemera like Kirby’s army uniform and his old typewriter are meant to round out the portrait but seem more like random artifacts from the attic.

The show’s most glaring omission is any exploration of Kirby’s complicated, stormy partnership with his peer, collaborator, and rival, Stan Lee, a fascinating, ego-driven love-hate relationship that goes largely unexplored. Its biggest achievement is elevating Kirby and his ilk to a status denied to them in their lifetimes.

“Because they were working in this popular medium, they weren’t seen as ‘capital A’ artists,” says Michele Urton, the museum’s deputy director and organizing curator. “Being able to see the artistry and get up close to the pages at the real scale gives you a completely different sense of the work.”

And a sense that, for Kirby, who died at the age of 76 in 1994, comic books were about far more than adventure. For him, they were morality plays. “The characters represent sort of a transcendent feeling that we all have inside us,” he once said. “That we could do better. That we want to do better.”

“Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity” is at the Skirball Cultural Center, 2701 N. Sepulveda Boulevard, Los Angeles, from May 1, 2025 to March 6, 2026

Michael Callahan is the author of several books, including The Lost Letters from Martha’s Vineyard