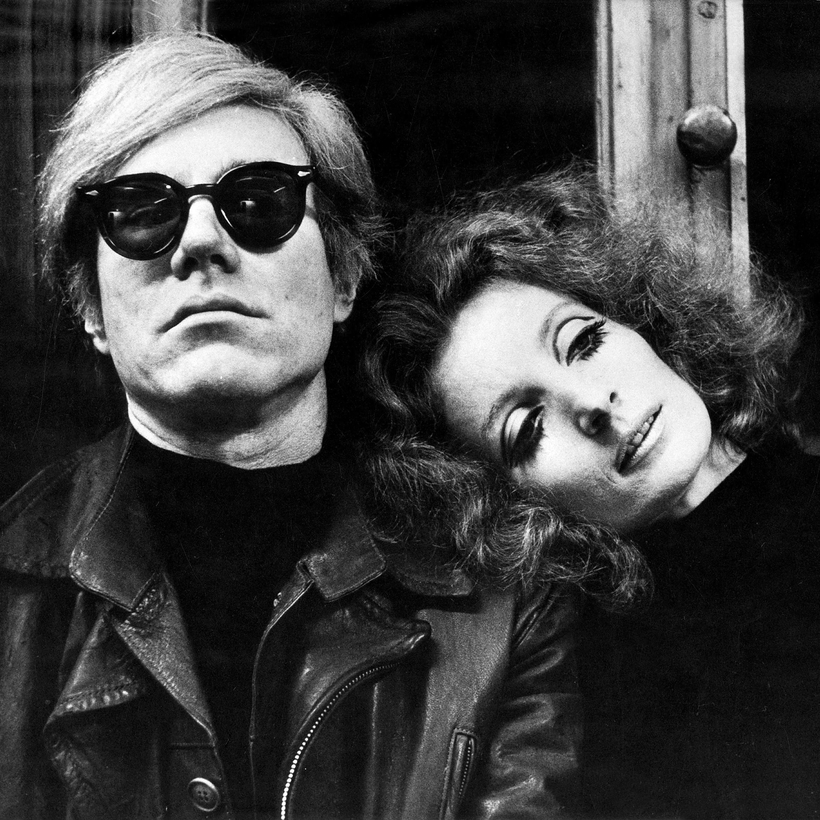

Nobody did opaque like Andy Warhol. The dark glasses, the sleepy utterances—he didn’t just immortalize the soup can, he practically was one, inanimate and sealed tight. But as such, was he also a kind of passive destroyer? That’s the premise of Warhol’s Muses, by Laurence Leamer, whose earlier group portrait, Capote’s Women, was the basis for last year’s FX series Feud: Capote vs. the Swans.

His new book is a mixed bag. His prose is adequate, if you ignore the clichés. (In the space of just three pages, we learn that Warhol golden girl Edie Sedgwick had “a wit as sharp as a surgeon’s scalpel” and that people “were drawn to her like flies to sugar.”) But his mission to consider Warhol through his dealings with a succession of devoted women and “superstars,” including “Baby Jane” Holzer, Ultra Violet, Viva, and the beautiful, doomed Edie, is illuminating—up to a point.

“Muses” would not be the term for what most of these women were for Warhol. With the exception of Edie Sedgwick, none of them really inspired any of his work, though all of them were dropped into films such as the experimental, split-screen Chelsea Girls and the shambolic gay Western Lonesome Cowboys. “Accessories” would be the better term, arm candy who helped get Warhol’s name and white-wigged picture in the papers. And the wealthy ones, which is to say most of them, also gave Warhol entrée into the upper-class circles he wanted so badly to enter, both for the social cachet and for the chance to promote his work to Park Avenue buyers.

In return, he introduced his superstars, bored with the subdued entertainments of the well-to-do, to a downtown art world that knew what it meant to party. The high-life-meets-low-life exchange was irresistible to both sides.

By the early 60s, with his soup cans and near-replica Brillo boxes, Warhol had ingeniously furthered Marcel Duchamp’s idea of readymades—“found objects” that became art simply because an artist said they were. As we know from Warhol’s biographer Blake Gopnik, an art-critic friend then suggested to him that he had extended that idea to people. Just as Duchamp had simply signed a store-bought urinal and submitted it to an exhibition, Warhol had turned a succession of obscure wannabes into “superstars” merely by calling them that. “Found celebrities”—he didn’t even have to sign them.

And was that so different from what real Hollywood moguls did when they polished the working-class Archie Leach into the impeccable Cary Grant? Or when they amped up the malt-shop soubrette Julia Jean Turner into the atomic sex bomb Lana Turner? Maybe not much, until you recall that the studios could bestow the wealth and fame of real stardom. Warhol could offer only the “underground” kind, ersatz, underpaid—if paid at all—and brief.

How brief? By the end of 1964, Warhol’s nightly outings with the married heiress Baby Jane Holzer, who took them from one party to the next in a chauffeur-driven limo, had landed her on the cover of British Vogue and gotten her declared “Girl of the Year” by Tom Wolfe. But within a few months, the widely read fashion columnist Eugenia Sheppard was declaring Holzer “highly overexposed.” In July of the following year, The New York Times Magazine duly pronounced on the pressing question of Who’s In and Who’s Out. Holzer? Out.

No matter. By that time, Warhol had met Isabelle Collin Dufresne, a wealthy young Frenchwoman and intimate of Salvador Dalí’s, who would take the name Ultra Violet. For their party-hopping nights, she dyed her hair with cranberry juice and carried a raw beet in her purse to touch up her complexion.

Eventually, there would also be Susan Bottomly, a Boston debutante whom Warhol renamed International Velvet, and the pre-Raphaelite beauty Viva. One of the few superstars without a trust fund was Ingrid Von Scheven, an occasional sex worker who was spotted in a shabby Times Square bar. Maybe for that reason she would get the most generic rebranding: Ingrid Superstar. Or maybe Warhol was just running out of names.

Warhol’s dealings with Sedgwick were his most complicated. Everyone who encountered her testified to her beauty, her crazy energy, her sheer charisma. By his own admission, even he sort of fell in love with her. But by the time they met, early in 1965, the 21-year-old Edie was already a mess. In and out of mental hospitals on both coasts, she was reckless, needy, and nihilistic. It was not a good sign that she accidentally set fire first to her Upper East Side apartment and then to her room at the Chelsea Hotel, but it was typical. As a sympathetic friend put it, in words that could have been her epitaph: “She was so beautiful and so helpless and so rich and so bananas.”

Sedgwick had grown up on a series of California ranches, the daughter of a manic-depressive father given to parading before female guests in a skimpy swimsuit. At the wedding of one of his daughters, he even tried to bed one of the bridesmaids. By the time Edie came east, two of her older brothers were dead. “Minty” had hanged himself in a mental hospital after telling their dad he was gay and being brutally rejected. Bobby, who had rebelled by becoming a left-wing labor organizer, died a few months later after slamming his motorcycle into the side of a New York City bus, an “accident” that Edie suspected was another suicide.

Sedgwick’s willingness to shock their dreadful father helped make Warhol’s world all the more seductive. The ambient drugginess, polymorphous sex, and performative decadence of the Factory scene were just the things to make her parents cringe.

Likewise for Brigid Berlin, whose father headed the media empire founded by William Randolph Hearst. Around the Factory she earned the name Brigid Polk for poking people with a hypodermic needle full of amphetamines. Having been fat-shamed in her teens by her fashionable mother, who put her on the diet pills that led to years of addiction, she would also strip naked at the slightest encouragement, or none at all.

Warhol presided over all this with his usual affectless manner. It was a pose, to be sure, useful shtick that let him disguise his genuine shyness as a hipster’s implacable cool, a mask he never let slip. Against the meth-addled backdrop of the Factory, he was like the Mister Rogers of the speed freaks. And in that persona he could disregard the headlong intake of pills and even heroin among some of his coterie, who treated self-destruction as just one more intriguing career path.

But Warhol didn’t lead them there. His own drug use was mostly confined to a daily Obetrol, a prescription pep pill that let him “work, work, work,” as he put it, late into the night. In As It Turns Out, a family reminiscence published in 2022, Edie’s eldest sister, Alice Sedgwick Wohl, insists Warhol didn’t get Edie hooked on drugs. “Nobody did,” she writes. “She came that way.”

Warhol’s final and most genuinely talented women weren’t actually women, at least insofar as they were anatomically male. Jackie Curtis, an Off Broadway playwright, presented variously as a man or a woman. Holly Woodlawn was more given to drag. Candy Darling was devoted to living full-time as a beautiful blonde. And on-screen all of them could be truly funny, especially in Flesh (starring Candy and Jackie) and Trash (with Jackie and Holly), two Warhol films—both actually directed by Paul Morrissey—that co-starred the somnambulant muscle boy Joe Dallessandro.

For them, at least, the Warhol association was a blessing. In an era decades before RuPaul’s Drag Race, cross-dressing performers were mostly confined to drag shows in tiny clubs. Warhol’s films gave his last superstars a wide audience they could never have found otherwise. Trash even played at New York’s prestigious art house Cinema II—right across from Bloomingdale’s.

After he was shot, in June 1968 by Valerie Solanas, a simmering anger bomb in his outer orbit, a shaken Warhol made the Factory more disciplined and businesslike. By the mid-70s he had largely shed his old followers. Who needed mock superstars when he could hang with the real thing, with Liza, Halston, and Bianca at Studio 54?

So Holzer eventually returned to high society. Berlin got off drugs and lived out her days in a chintz-laden apartment, still addicted, but by then to Fox News. Ultra Violet became a Mormon. Ingrid Superstar moved in with her mother, in Kingston, New York, and worked in a sweater factory. One day in 1986 she went out for cigarettes and vanished.

Sedgwick didn’t have time to repent or even disappear. She moved back west, convinced Warhol had exploited her in films that drew too plainly on her messy life. In 1971, after more hospitalizations, she died in her sleep of a barbiturate overdose, aged 28. On hearing the news, Warhol changed the subject.

In the end, Leamer indicts Warhol for what might be described as emotional malfeasance. The Factory was a toxic playground whose pathologies Warhol merely observed, when he should have somehow intervened. As for his superstars, “he used these women, and for the most part discarded them.” It might be truer to say they used each other, often to mutual benefit. All the same, those women included some precarious souls, Edie above all, whom the self-enclosed Warhol was in no way equipped to watch over, much less rescue.

In her book, Edie’s sister says that people who think Warhol destroyed Edie are wrong. “What destroyed her are all the forces that made it inevitable she would destroy herself.” Would Warhol agree? It’s too late to ask, but he probably wouldn’t say. As mentioned, nobody did opaque like Warhol. Actually being dead has only made that easier.

Richard Lacayo is the former art-and-architecture critic at Time and the author of Last Light: How Six Great Artists Made Old Age a Time of Triumph