Maia hasn’t visited her aunt, who lives in Germany, since 2015. The last time her 72-year-old mother saw her 68-year-old sister, aside from on their regular FaceTime calls, was 2019. After the pandemic delayed their travel plans, they had hoped to re-unite this summer when Maia’s aunt visited the U.S. for two months.

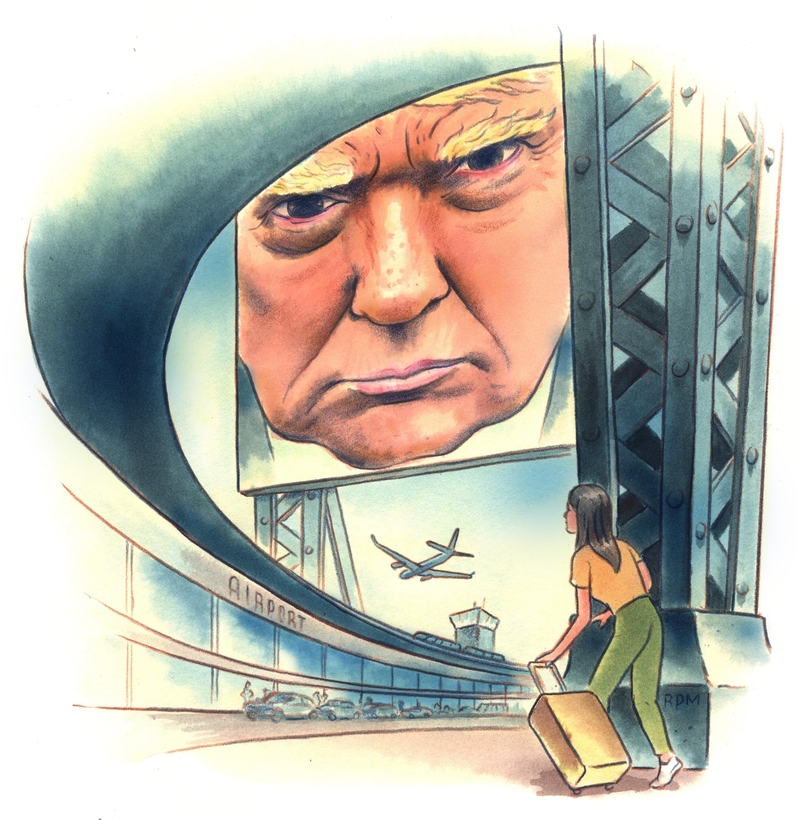

But the family scrapped their plans when Germany issued a travel advisory for visiting the U.S. in March after several German citizens were detained at the border. The German foreign ministry warned that even a U.S. visa or approval through the U.S. Electronic System for Travel Authorization would not guarantee entry. That proved to be the case last month for two teenage girls from Germany who were detained by immigration officials in Hawaii and forced to spend the night in a freezing holding cell.