“Open the damned gate!” the old man commanded in his Georgia drawl behind the wheel of his snub-nosed black Bentley at the gates of his golf company’s testing center. “It’s Ely Callaway!”

Damned right it was. Ely Callaway, then 78, four times married, was at that moment a supreme titan of the golf industry, prowling his sprawling Callaway Golf–company hallways, fairways, and factory, “400,000 square feet in eight buildings, a plant where a new cart of clubs comes off the line every five minutes, around the clock,” I wrote back then. “Three shifts of 1,800 workers try to keep pace with demand.”

The bankroll in his britches was fat with his trademark $2 bills, and a line of officers he had transformed into multi-millionaires with Callaway stock options followed his every step, desire, and command.

He was also, unbeknownst to me, a man on the run.

It was 1995. I had come to interview Callaway over several days for a Golf Digest–magazine profile that would be entitled “So Tell Us Ely Callaway, How Did You Earn Your Third Fortune, Revolutionize the Golf Business, and Make Big Bertha into a Household Name?” To which he answered, “We did it with smoke and mirrors.”

Oh, how true that quote would turn out to be!

The story I wrote was about the business dynamo who had struck a series of gushers, two bona-fide bonanzas after leaving his perch as the president of Burlington Industries and moving to Southern California in 1973, where he hit it big, first with Callaway Vineyard & Winery, and then even bigger (and richer) with Callaway Golf.

But the story I missed was that Callaway had come to California not as a wine or golf magnate but as a man on the run from what would become a lifelong secret—revealed only now in his autobiography, publishing this Tuesday, 24 years after his death, entitled The Unconquerable Game: My Life in Golf & Business.

He was on the run from Burlington Industries, the New York textile giant where he had been named president in 1968, and where he was on his way to becoming C.E.O. Then, over the July 4, 1968, weekend, a courier arrived on the train to Stamford, Connecticut, near Callaway’s home in New Canaan, from Burlington’s new, 50-story Manhattan world headquarters with what Callaway would soon regard as some very dirty papers for him to sign.

While the courier waited, Callaway dutifully signed the papers, and he read them only later over the holiday weekend, with growing astonishment and alarm.

Callaway had put his signature on a Federal Trade Commission consent decree prohibiting Burlington from investing or acquiring any textile mills or textile products for 10 years—an agreement which, Callaway would later contend, Burlington would violate (or had already violated). Even as the company’s president, Callaway, who had joined Burlington in 1956, writes that he knew nothing of what became known as “the Madison Matter,” in which Burlington had failed to acknowledge to the F.T.C. its majority stake in a company called Madison Throwing Company (which produced nylon in Madison, North Carolina). But Callaway felt sure he was being set up to be the fall guy since his was the only signature on the consent decree.

“For the next five years, Ely tried to convince the members of the Burlington board that what they were doing was morally, ethically, and practically wrong; that they must correct that wrong by doing the right thing both in its dealings with the U.S. government, shareholders, and the media; and that they must absolve him and indemnify him of the responsibility and liability they had tried to shift onto him as a way to shield themselves,” Callaway’s son, the publisher Nicholas Callaway, recently told me.

When, in March 1973, he threatened to turn whistleblower, Callaway was “fired by his boss, Charles Myers, the C.E.O. of Burlington, whose position Callaway had been told he would assume when Myers was scheduled to retire in 1974,” says Nicholas, leading Callaway into exile in California. Before leaving, however, Callaway put 200 pages of evidence into a dossier—conversations, memos, and other documents supporting his stance—for safekeeping. He also detailed everything in a 23-page letter, stuffing it into an envelope on which he scrawled, “To Be Opened Only After My Death,” and telling no one, not even his family, about the secret he would carry to the grave.

Now that the dossier has been opened—and put into Chapter Four of his book, entitled “The Madison Matter: The Secret I’ve Never Told That Forced Me to Start Over at the Age of 53”—the story of Ely Callaway has even more resonance.

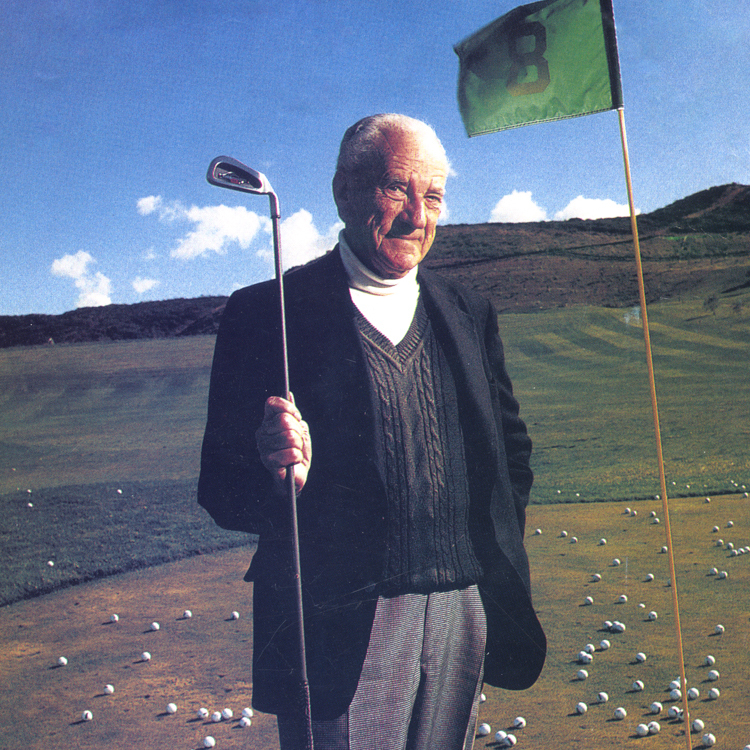

“Tall and patrician, with an old South gallantry, Ely Callaway seems the perfect figurehead for golfdom’s boomtown (of Carlsbad),” I wrote in the Golf Digest profile, noting that his office walls were filled with photographs of Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Ford, all “swinging Callaways,” and how during our interview a gift arrived from the King of Morocco. “Oh, good Lord, it’s a prayer rug,” Callaway drawled. “They came in the other day and said they needed some clubs.”

Over nine pages, I included pretty much all he would reveal. How he left Burlington and New York, having negotiated a sizable severance. How he bought a $15,000 tract house in the California desert and defied the Southern California sun—“Everybody said, ‘You can’t grow grapes in Southern California! It’s too damned hot!’” he told me—by finding a micro-climate with Napa Valley weather in Temecula and marketing the hell out of his products. (“He could sell Eiswein to Eskimos,” Robert Mondavi once said.) How he made a third fortune with Callaway Golf, which he built into the world’s largest golf-club company. (It went public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1992.)

I left with a story but hardly a scoop, which he was obviously saving for an autobiography he must have considered too hot for publication in his lifetime. Still, he had begun writing it—without revealing the Burlington secret—with what would turn out to be four collaborators: ace golf writer Larry Dorman, who would become Callaway’s vice president of public relations; Time-magazine editor John Huey; legendary Texas writer Bud Shrake, who collaborated on the best-selling Harvey Penick golf books; and the writer and playwright Andrew Moorhead, who worked on the book with Callaway’s son Nicholas after Callaway’s death, spending six years on the project.

The result is The Unconquerable Game, referring to the game of golf, which Callaway described during our interview as “the most complicated, most difficult known to man. It’s one of the most frustrating. Therefore, it’s not very rewarding. It’s addictive!”

“Now turn that thing off,” he said into my tape recorder, at which point he regaled me with off-the-record stories “strong as Georgia moonshine.”

He is equally feisty on the page.

“As long as you’ve got a good story you can convince anybody of almost anything,” he writes. “Sixty years ago, in 1971, one of my stories convinced the New York Mafia to help me, a 21-year-old kid from LaGrange, Georgia, procure $350 million worth of uniforms ($4.2 billion in 2001 dollars) for the U.S. Army during the Second World War. Over 25 years ago, in 1974, I persuaded the Bank of America to loan me a million dollars over a few sips of wine. And 10 years ago, in 1991, I prophesized to the golfers of the world that if they tried a strange-looking driver with a funny name, and an even funnier sound, made by an itty bitty company that they had never even heard of, it would change their lives and the game of golf forever.”

His book is a riches-to-riches-to-mega-riches story, filled with, being Callaway, successive money-making moments. But for me, the invention of the driver that would revolutionize golf is second only to the revelation of the Madison Matter.

In the summer of 1990, Callaway’s senior executive vice president and club design wizard, Dick Helmstetter, “plopped” something onto his desk: “the first oversized stainless-steel clubhead … bigger than normal at the time. It was also ugly. But it pleased me in a way I couldn’t quite put into words. I told Dick to stick the head on a shaft so that we could take it for a spin.

“On my second shot, I hit the driver off the fairway, and the ball fired directly to the pin. As good a player as I was, I could not hit this kind of shot from the fairway. The trajectory as it rose into the air was more like a tee shot than an approach shot—it felt like it had been propelled out of a cannon rather than ricocheting off the club face.

“Because of this feeling, the name of our new driver came to me almost immediately.... It was not uncommon for people to name golf clubs after weapons—Spalding came out with a series of clubs called ‘The Cannon’ in the mid-1980s.”

At that moment a name arose from Callaway’s World War II army days: “a giant World War I German howitzer invented by Friedrich Krupp AG, the largest weapons manufacturer in Germany,” a cannon that “shot artillery shells farther and straighter than any other.”

It was nicknamed Big Bertha, as was Callaway’s revolutionary driver, which superpowered the game with a stick that struck a golf ball like a howitzer cannon. By the time Callaway died, at 82, in 2001, the Callaway Golf company had a larger market capitalization than Burlington Industries when he was its president.

As always, Ely Callaway emerged a winner, as he does once again with this book.

Ely Callaway narrates the audiobook version of The Unconquerable Game: My Life in Golf & Business with the help of A.I.

Mark Seal is a special correspondent for Vanity Fair and the author of many nonfiction books, including The Man in the Rockefeller Suit and Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli, recently made into an AIR MAIL podcast