In 2023, the New York–based Foundation for Italian Art and Culture approached the Cincinnati Art Museum (C.A.M.) with a project. Would it like to support the restoration of two works by one of Italy’s greatest painters of the Renaissance—Tintoretto—and then show them? The paintings, part of a series based on stories in the book of Genesis, were in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, in Venice, where the restoration work would be done.

For Peter Jonathan Bell, the curator of European paintings, sculptures, and drawings at C.A.M., the chance to show The Temptation of Adam and Cain and Abel was “a crime of opportunity,” he says. “These are amazing paintings.”

Bell suggested that the project should expand to include the Accademia’s third picture in the series, Creation of the Animals. All date to the early 1550s. (Two more paintings in the series—one at Florence’s Gallerie degli Uffizi and the other in a private collection—were not part of the project.)

“Tintoretto’s Genesis” opened yesterday at C.A.M., and the three restored pictures are now on view, along with drawings and a display illuminating the restoration process. For Americans, this show is a rare treat. Tintoretto’s masterpieces were created in Venice, and even his works not painted on walls or ceilings rarely, if ever, leave home.

In the 19th century, when the British critic John Ruskin called The Temptation of Adam and Cain and Abel “the finest possible Tintorettos,” he labeled them “dark paintings.” But after a year in which old varnish and earlier restorative errors were removed, they are dark no longer. Equally important for Bell is the “pivotal” place of the series in Tintoretto’s career. The artist was just coming off one of his first major successes, the massive The Miracle of the Slave (1548), with its novel, adept, and dramatic treatment of bodies in action.

In his mid-30s, Tintoretto was struggling under the shadows of rival painters, particularly Titian. As a member of some of Venice’s powerful societies, Bell explains, Titian could keep corporate patrons from choosing Tintoretto. It was one of Venice’s smaller charitable organizations, the Scuola della Santissima Trinità, that hired him for the Genesis series. The three paintings in the show demonstrate the dynamism Tintoretto was already wielding at that time. Even in Creation of the Animals, which is more decorative than the other two, we see God, buoyed in a golden glow, conducting new species of the air, land, and sea swiftly into existence.

In The Temptation of Adam, Tintoretto’s composition is a powerful drama of seduction. Eve leans toward Adam with the apple; he shrinks back. As Bell points out, their diagonal forms mirror each other. Having tasted the fruit, Eve has covered her genitals with leaves, in shame; Adam remains innocent and naked. Staring at the apple in her left hand, in thrall to it, Eve is in danger of sabotaging her attempt to get Adam to bite. The serpent, the same color as the tree, stretches its head toward Eve’s right hand, a backup apple in its mouth. On the far right of the picture, in the distance, the dénouement is already in play: a fiercely glowing angel drives the couple out of Eden.

Cain and Abel portrays the last moment of the brothers’ combat, incited when God preferred Abel’s offering from his flock over Cain’s fruits of the soil. Cain, upright, has one arm on Abel’s neck, the other raised and wielding a stick with which to deliver the death blow. Abel, his balance lost, is falling and cannot protect himself.

We barely see faces, only a pinwheel of arms, legs, and backs, muscles straining. Abel’s offering, a slain calf, lies on the ground, its dead eye trained on its besieged master. During the restoration, imaging technology showed how Tintoretto fussed over this picture, adjusting the brothers’ limbs, changing Cain’s grip on his weapon. Seeing the painter’s hesitancies only heightens his achievement.

“Tintoretto’s Genesis” is on at the Cincinnati Art Museum until August 31

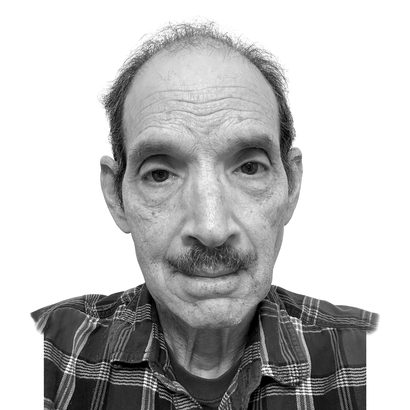

Peter Saenger has written and edited for The Wall Street Journal on such topics as art, art books, museums, and travel. His fiction has appeared in The New Yorker