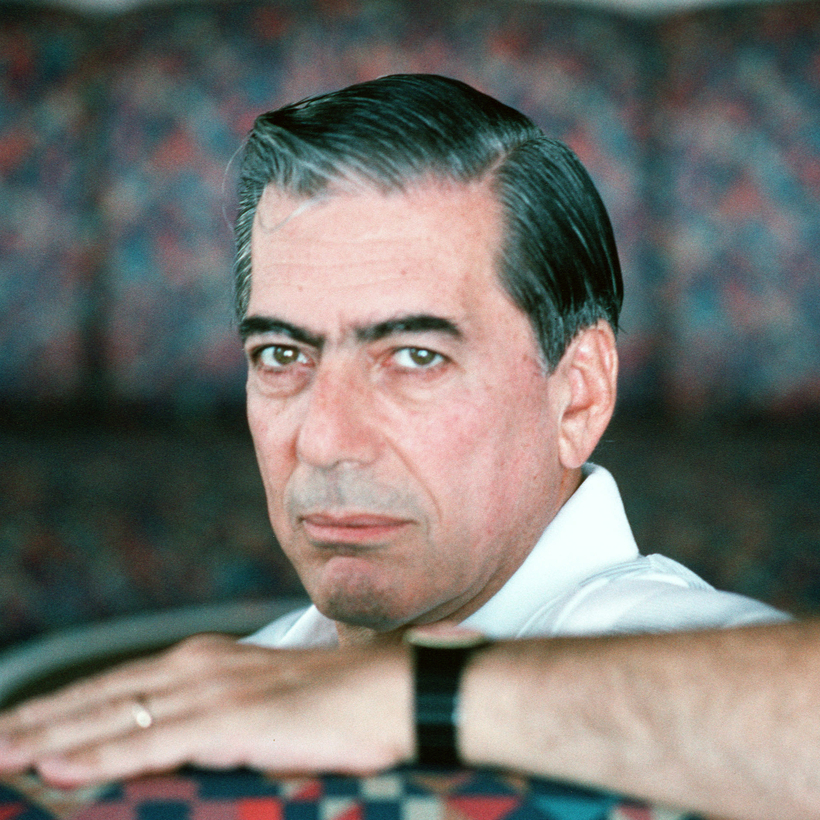

I met Mario Vargas Llosa in the late 1980s. I had been commissioned to adapt his novel Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter as a movie for a Hollywood mini-major called Cinecom. By good fortune we had a mutual friend, the writer Nicholas Shakespeare, and it was Nicholas who introduced us. Mario invited me to dinner — he had a flat in Knightsbridge, London, in Montpelier Square, at the time — and was very excited about the potential film of his novel. I was a fan and Aunt Julia was my favorite among his many novels. But I had bad news to impart.

Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter is both very autobiographical and very fantastical. Set in 1950s Lima, Peru, it follows the love story between Mario, the novel’s young protagonist, and his aunt Julia. Their story parallels Vargas Llosa’s affair with Julia Urquidi, a woman 13 years his senior whom he eventually married. The story is interspersed, however, with a dozen or so crazily surreal soap operas, written by the eponymous scriptwriter, one Pedro Camacho.