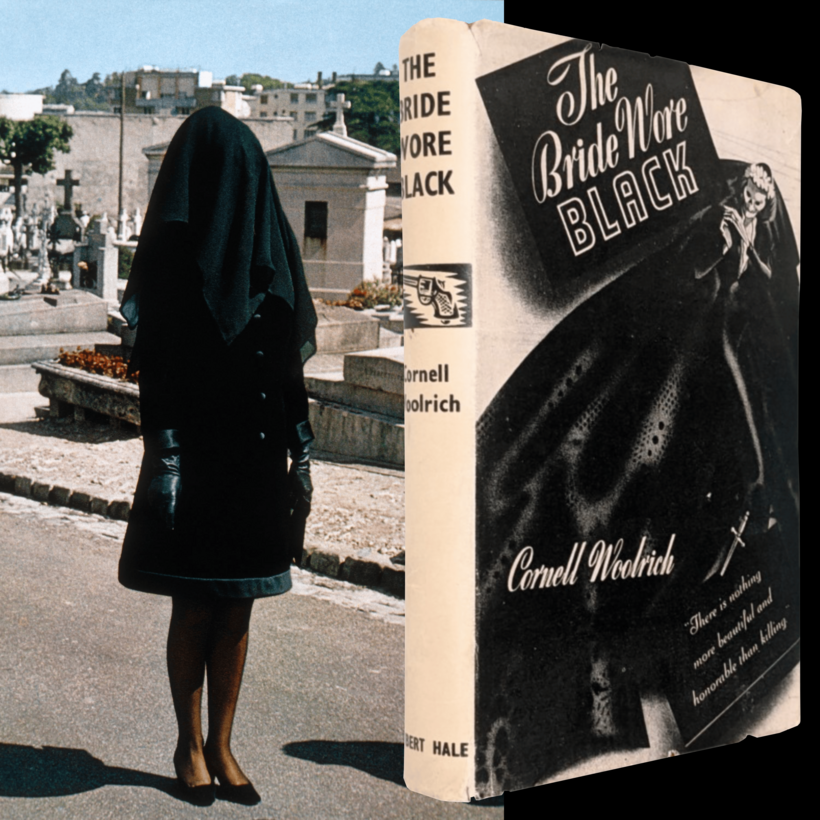

No one much liked the solitary writer Cornell Woolrich, except Hollywood, which devoured many of his noir novels and short stories, with their ingenious plots, solitary losers, and complicated protagonists.

Alfred Hitchcock turned one of Woolrich’s novelettes into Rear Window, for which Woolrich was paid the grand sum of $650. (“But that’s not what bothered me,” Woolrich later recalled. “What bothered me was that Hitchcock wouldn’t even send me a ticket to the premiere in New York. He knew where I lived.”)