In 1968, in the months after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) decided to honor the man with an exhibition. Works by artists such as Mark Rothko, Robert Rauschenberg, and Alexander Calder would be shown and then sold to benefit King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Everything was going as planned for the October opening, until somebody noticed that the organizers had failed to include art by people of color. The oversight was addressed but only insofar as the selected works by Black artists were hastily displayed in a small room away from the main exhibition space. One of those works was For M.L.K. (1968), an abstract painting by Jack Whitten.

Whitten, who died in 2018, at 78, is now the subject of a vast solo retrospective, “Jack Whitten: The Messenger,” opening tomorrow at MoMA. The exhibition brings the artist’s career full circle, and not just because of Whitten’s inclusion in the King show.

MoMA was the first art museum that Whitten visited after he moved, at the beginning of the 1960s, from segregated Alabama to New York City. And it was at MoMA that Whitten saw Cézanne’s The Bather, which he identified as a “baptism.”

Whitten moved beyond figuration, however, to become an abstract artist when it was not a path expected of Black painters. “This was throughout a period of time starting in the 1960s, when Whitten was actually under a great pressure to create art that was figurative or activist or explicitly addressing social issues through realistic depiction,” Michelle Kuo, the exhibition’s curator, told me recently. “His utopian hope in some ways was that by changing the way you see, his art might actually change the way you act in the world or see others.”

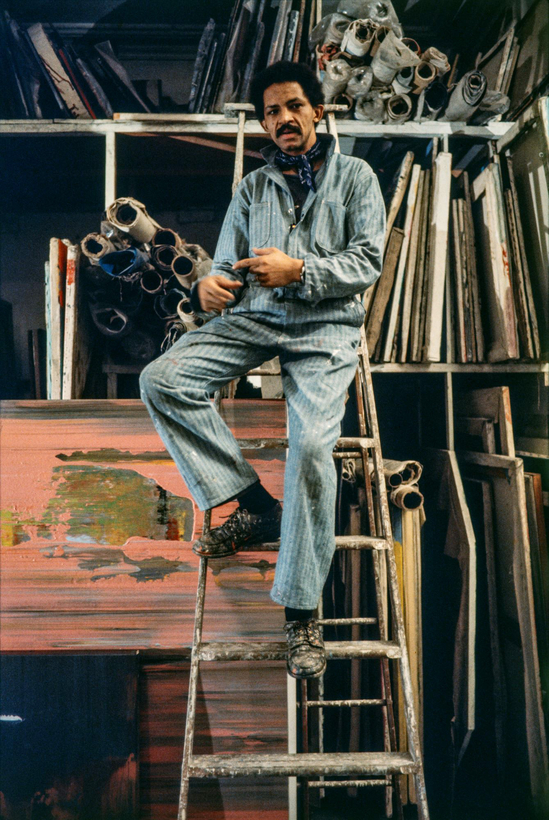

The MoMA show (its title nods both to the breadth of Whitten’s vision and to his love of jazz, in particular the music of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers) places a notable focus on 1974. That was the year in which Whitten came to prominence with a pioneering solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Up until then, he was largely known for Abstract Expressionist paintings inspired by the gestural style of Willem de Kooning and Arshile Gorky. But in the early 1970s, Whitten invented a large T-shaped tool—he called it “the developer”—that enabled him to pull layers of acrylic paint across a large canvas on the floor of his studio.

“So instead of many brushstrokes, you have one stroke, one pull,” Kuo says. “These works at the Whitney looked almost like you were seeing something from a camera in motion or a speeding vehicle or even something like a radar scan. It was the first time an artist created this kind of blurred motion in painting.”

In 2012, when Kuo was the editor of Artforum, she interviewed Whitten and put one of those “blurred” paintings—Pink Psyche Queen (1973)—on the magazine’s cover. “I was mesmerized by his paintings and also his relationship to technology,” she said. “I think that cover set off a number of new conversations about his work. But still a lot of people aren’t familiar with his art. In part, I think, it’s because it is so shape-shifting. That series of ‘blurred’ paintings is just one facet of his work. He also made sculptures and incredible works on paper as well.”

“Jack Whitten: The Messenger” will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, from March 23 to August 2

Tobias Grey is a Gloucestershire, U.K.–based writer and critic, focused on art, film, and books